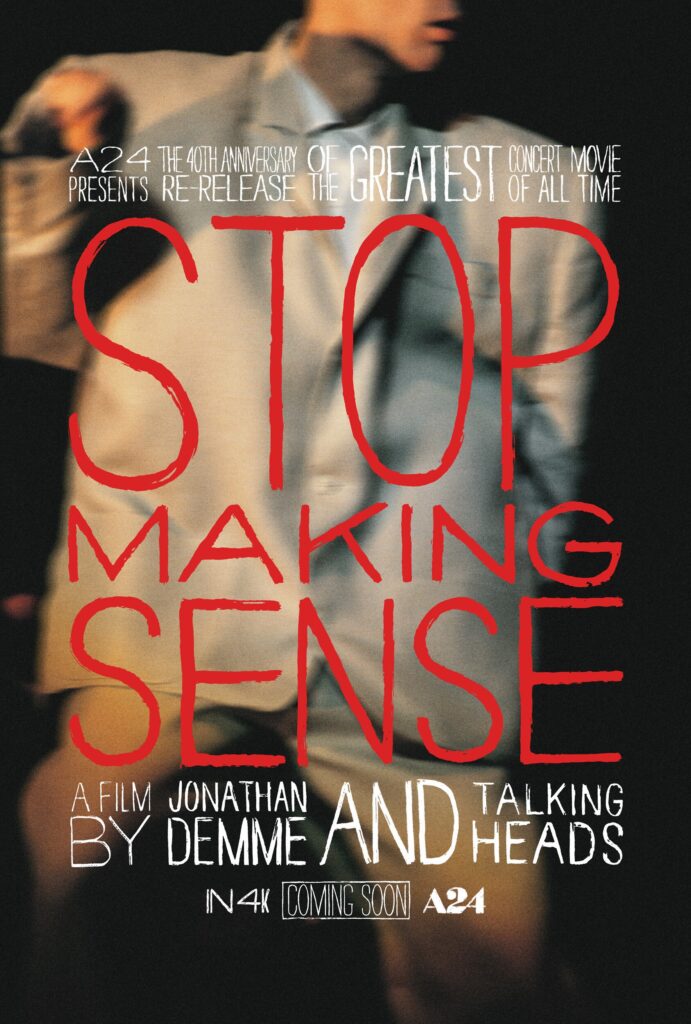

One dark December in 1983, American rock band Talking Heads spent three frenzied evenings recording their most well-loved songs in a Hollywood theatre. The resulting body of work, directed by Jonathan Demme, comprises nineteen songs and spans eighty-eight ecstatic minutes of runtime. Now acquired and restored by production company A24, Stop Making Sense returns to the silver screen to mark 40 years since its’ initial release.

Track seven of the re-released vinyl which accompanies the film is ‘Life During Wartime’. It is a bastion of experimental new wave, immersing the listener in a dystopian narrative rich with the darkly funkadelic synth grooves which would define the pop canon of the ‘80s.

The song, produced by ambient pioneer Brian Eno, was the lead single from 1979’s Fear of Music. Itfollows the story of a revolutionary character grappling with a deeply oppressive state: an existence characterized by clandestine operations, and one that is ceaselessly in motion to evade perception.

The chase is ubiquitous and urgent, reflected in the propulsive 4/4 beat which drives the piece. Drummer Chris Frantz is insistent, and he does not come up for air until the recording decrescendos into the static silence between tracks.

The notion of pursuit is doubly emphasized by the band’s dynamic performance in the concert film.Led by singer David Byrne, we see the whole ensemble jogging on the spot as the arrangement builds and swings into a thunderous fever pitch.

Like much of the production, ‘Life During Wartime’ has been arranged differently for performance. In lieu of the immediate jaunty stride of the studio recording, the listener is at first teased and tantalized by keyboardist Bernie Worrell. While the applause still rings out from the hugeness of ‘Burning Down the House’, the first chords begin to fade in from the backline, joined after eight bars by Frantz. The six-minute masterwork is assembled brick by euphonious brick, providing a credible foundation for Byrne’s singularity.

When the first chorus tumbles in with a squall of gang vocals, hair is coming unstuck and hanging in dark strings in Byrne’s face; a sheen of sweat already visible on his philtrum. He recoils animatedly from the microphone with each utterance, his mouth wide open to satisfy the full, blaring breadth of sound.

By the second chorus, the figurehead is miming an exaggerated breaststroke. His limbs appear as if they are manipulated by an unseen puppeteer, though he is in full command of the uncanny display. Those with a keen eye will observe him smiling between breaths, deliberate in his peculiarity.

Midway through live recording, most of the band withdraws from the melee for a full sixteen bars. Byrne dictates a subdued verse, steered by Frantz’s incessant timekeeping. Tina Weymouth’s rolling bassline and Worrell’s staccato keys quietly maintain the chord progression, before the entire outfit surges back into a colossal chorus. We hear the sonic constituents which make the composition so interesting: the building, dismantling and rebuilding of tension. Music students will learn that the most vital element of song is silence: Talking Heads’ expert texturing demonstrates that they are top of the class.

The world of Byrne’s narrator was and is alien to much of the song’s audience: that’s what makes it so compelling. Many would struggle to comprehend a daily existence in which gunfire, mass graves and roadblocks are commonplace, but it is striking how near these descriptions are to the realities of besieged and oppressed populations in the present day.

Still jogging in place, Byrne delivers the lines, “What good are notebooks? / They won’t help me survive”, seemingly lamenting the incapacity of creativity to act as practical defense. Whilst this is true in a superficial sense (paper cannot ordinarily stop bullets), the narrator fails to consider what the notebooks can represent. For centuries, writers have been creating poetry of witness, documenting their experiences of war, suffering, oppression, and trauma. These accounts are invaluable: to our understanding of hardship, the preservation of history, the amplification of marginalized voices and the emotional catharsis of the writer. In Forché and Wu’s 2014 book on the topic, they note how poets continue to write ‘despite all that has happened, and against all odds’. Lorde, Sexton, Juma, Kaminsky, and countless, countless others subscribe to this ethos.

The song’s lyrical hook, “This ain’t no disco”, has also defied interpretation for over four decades. Early on, some heard the refrain as a rally against the genre, an affront against disposable music. But many of the song’s structural components would suggest the opposite. The 133 beats-per-minute tempo, the four-on-the-floor drum beat, the heavy use of synth and repeated lyrics are all archetypal of the disco philosophy. In contrast with early interpretations, American Songwriter suggests that the lyric is a reference to how such a volatile and prohibitive dystopia would remove any opportunity for frivolity in daily life.

Disco itself has its roots in a culture of oppression, finding its home in the underground clubs of ‘60s America: it was a direct response to a cruel and unaccommodating world. Its campness, its silliness, and indeed its frivolity, were war cries from Black and LGBTQ+ artists in a hostile musical landscape. From Donna Summer to Boney M. and Sylvester, disco represented an environment away from the harsh realities of a racist and queerphobic society, positioning a lit-up dancefloor as a shelter from a fusillade of abuse.

‘Life During Wartime’, and David Byrne’s strained performance continue to raise important questions: about creativity, freedom to celebrate in the face of oppression, and the attempt to foster community in an unpredictable climate of conflict. In moments of unrest, persecution and tragedy, the legacy of Talking Heads reminds us to hold onto joy and its capacity for resistance.