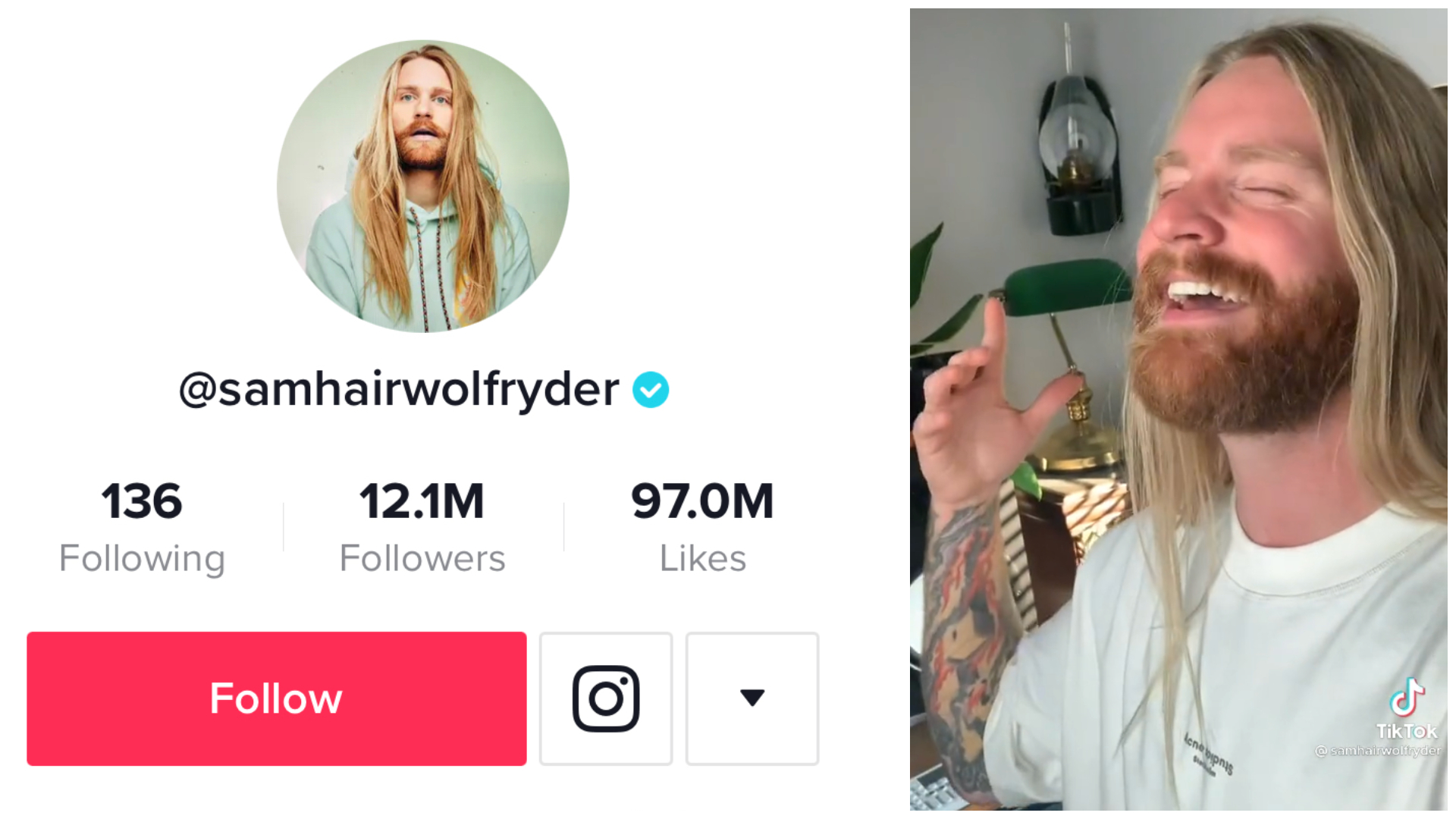

Recently, TikTok launched a advertising campaign entitled ”Where stars get started’, for Eurovision starring Sam Ryder, who was also announced as TikTok’s official Eurovision ambassador. Appearing on billboards across Liverpool, TikTok said the adverts would shine a light on how “stars get started” on their platform and claims it will show how other artists can follow in his footsteps.

There’s no doubting Sam Ryder is a sensation on the short video clip platform with over 14 million followers and 127 million likes. He started his TikTok journey by posting uplifting acoustic covers especially over lockdown, which were duetted by celebrities like Alicia Keys, leading to Ryder signing with Parlophone and performing at Eurovision for the United Kingdom and topping charts, since his second place finish last year.

He’s also scored high charting singles, international touring and remains the most followed UK artist on TikTok. But is TikTok merely the platform he used to help gain virality? Is it really the place he “got started”? Or did he hone his skills over many years, in small venues, small recording studios and in bands supported by music labels. Well, Music Venue Trust’s Mark Davyd took issue with the advert in his recent blog on substack “I thought about reporting it to the advertising standards agency, but they are bored of my phone calls about tech platforms passing themselves off as music companies.”

“There’s going to need to be a re-calibration of all the ludicrous claims being made about how we supposedly ‘create’ artists on these platforms.”

“Because TikTok didn’t build Sam’s playing skills. TikTok didn’t teach Sam to write great songs. TikTok didn’t teach him how to enthrall and manage an audience of people. TikTok didn’t even help style him.”

“TikTok delivered a platform for him to get exposure – in Sam’s case, specifically during the pandemic when his talent really had a chance to shine on the platform TikTok provide. I bet Sam is super grateful for that, and probably got paid really well for the supersized use of his image.”

“But that doesn’t make the claim that TikTok is ‘Where Sam Ryder Got Started’ any less misleading or deceptive. Companies like TikTok are reliant, just like every other part of the music industry – and increasingly the tech exploiters of that industry (I’m looking at you Spotify) – on one simple activity that none of them seem prepared to invest in as part of their business.” explains Davyd.

Whilst TikTok can be a useful platform for growing a fanbase and streams, like Spotify, there are challenges and #BrokenRecord inequalities from tech companies and their claims that they “made” certain artists don’t stand up to scrutiny and also highlight their lack of investment back into most artists and their careers, in the form of fair royalties.

Pointing out that Sam had previously been in a band called The Morning After who had released two albums and spent years on the circuit before he went viral, Davyd explained “At the age of 11, Sam Ryder was inspired to pursue a career in music after seeing the Canadian rock band Sum 41 in concert. In the simplest of cultural terms, he had the opportunity to see it and he decided to be it.”

The royalties that artists receive come from TikTok’s revenue, which appears to be a complex arrangement which means the distributor such as Tunecore, collects the royalties on behalf of the artist and pays them out. Each distributor has their own deal in place to determine how much artists are paid for their song use on the app. The earnings are significantly less than what an artists gets from a Spotify stream, as often only a small portion of a song is featured in the videos. According to the most recent data available, “TikTok pays three cents(£0.000227) for each new video in which your song is played. So it would take 1,000 videos featuring your music for you to make $30(£24). According to these numbers, 1,000,000 uses of your track would bring in about $30,000(£24,079)”

Other estimates online say TikTok royalties were close to $0.0067(£0.0054) per video that uses an artists music in 2018 and moved to $0.030(£0.24) per video in June 2019.TikTok operates differently to Youtube when calculating royalties and calculates it on the number of videos made using an artists music, rather than how many times the video is watched. So big view counts don’t necessarily equal large royalty payments. The quantity of videos matters more than the total view count. TikTok uses what is called “a creation.” A creation is when a user selects a release from TikTok’s library to make a video. Users can then make their own creations and memes inspired by existing creations, all amounting to new creations. So, every time a user decides to use an artists music to make a video, this generates royalty.

According to Music Business Worldwide, TikTok made £4 billion in 2021 and according to Goldman Sachs Music In The Air report, they paid recorded music rights holders (i.e. labels and artists) a grand total of around $179 million in 2021. In contrast to Youtube, TikTok does not pay out a share of advertising based on plays. Instead, it licenses music from major record companies via individual “blind check” payments, each of which covers a certain period of grace. In these grace periods, TikTok (and its users) can incorporate copyrighted music as much as they like.

With a younger demographic than other video platforms, with 22% of users between 18 to 23 and 54% users are female and 46%male. TikTok boasts a impressive record of virality with songs that trend on the platform often ending up charting on the Billboard 100 or Spotify Viral 50. And 67% of the app’s users are more likely to seek out songs on music-streaming services after hearing them on TikTok, according to a November 2021 study conducted for TikTok by the music-analytics company MRC Data.

Artists like Wet Leg, Maisie Peters, Nova Twins, Cassyette, Lil Nas X, Lizzo, Doja Cat, Panic Shack, and Sam Fender to name a few have successfully used TikTok as platform to go viral, connecting with audiences on a direct level through snappy visuals and relatable lyrical themes. Released in June 2021, ‘Chaise Longue’ was suddenly everywhere, on rotation on radio stations, social media platforms and Spotify playlists. By the time Isle of Wight act Wet Leg’s self-titled first album was released, they had moved from nowhere to one of the most hyped acts in the country. The band joined TikTok after they released ‘Chaise Longue’ and immediately started using it to communicate with their fans directly, their Victorian fashion style, visuals and impish song lyrics connecting with their audience on a more direct level.

With 500,000 followers, Wet Leg combined their songs with strong imagery and lyrical themes that chimed with their fans.

@wetlegband Fanx @bbcradio1 Big Weekend 🌝 #wetleg ♬ Chaise Longue – Wet Leg

“We didn’t aspire to get signed. We thought it would not be on the cards,” Wet Leg’s Hester Chambers told the NYT modestly. “We just wanted to play some silly songs.” But when people learnt the pair had been signed for months and they had worked as costume directors on videos for the likes of Ed Sheeran, the sense that a lot of work and investment had gone into making Wet Leg a viral sensation lingered, leading some to daub them “industry plants”. Perhaps ignoring the fact that they had been working as solo artists for many years and without the quality of songs that connected with people and the personality to back it up they wouldn’t have even been signed by Domino or gone viral in the first place. There have been a litany of acts in music history who have been hyped by the music press or had big backing and never taken off.

Who is to say what kind of music is more worthy than another anyway? The disparity between unsigned, DIY label acts and those on major labels or big indies is starkly highlighted more in this era of streaming inequalities where the viral bands and top 1% of artists take the attention and baulk of the proceeds and everyone else struggles often playing in small venues trying to make it work economically alongside a 9 to 5 job. There are very real issues around privilege and nepotism too, I mean are Inhaler, who are led by Bono‘s son ever pulled up for being “industry plants”? But can we really begrudge acts like Wet Leg their success when it’s hard for ANY artist to make it to make it in this era where on average it can take up to five years to “break a band”, plus when you look at the backlash online to other acts like Panic Shack and The Last Dinner Party, much of it has the bitter and really unpleasant ring of real music snobbery and misogyny about it, rather than purely musical critique.

@thelastdinnerparty If this is on your feed congratulations that tiktok thinks you have excellent taste in new bands. Please accept our cordial invitation to enjoy our new song 'Nothing Matters' 🏹 #NewMusic #AltMusic ♬ Nothing Matters – The Last Dinner Party

For the record, I for one quite liked ‘Chaise Lounge’ as a single it’s catchy and has a irreverent wit, the lyrics have a surreal suggestive quality that are playful and give off a “don’t mess with me” air that appeals to many, but I found the debut album didn’t quite live up to the hype musically or lyrically, but Wet Leg’s indifference to fame and ability to not take themselves too seriously, is perhaps part of their appeal especially for their female audience and those who identify with them and buy into their experiences as self empowered women. Also, their willingness to just say what they think, to have fun, to take the piss, this is as much part of their appeal than any of their songs.Their songs can also be reinterpreted and represented in TikTok memes by their fans, this kind of personal reaction and modification of your favourite song is part of what makes TikTok so interactive for many users.

“One of my favourite things that they do is they’ll respond to comments. It essentially promotes their music at the same time but all their comments are a little bit tongue-in-cheek, and do a really great job of showing their personality,” comments Sheema Siddiqi, Artist Community Manager at TikTok UK.

Lizzo’s ‘Truth Hurts’ became a big hit two years after it was originally released in 2017, with its first line being so recognisable from trending TikTok videos, featuring fans lip syncing or dancing to the song that it was re-released as a radio single.

In 2021, Sam Fender’s ‘Seventeen Going Under’ went viral on Tik Tok. The songs central lines: “I was far too scared to hit him / But I would hit him in a heartbeat now / That’s the thing with anger / It begs to stick around” became the backing track to thousands of TikTok videos by users, lip syncing to the lines and sharing their own experiences of abuse with imagery or in accompanying text.

Fender told the NME: “It’s been wonderful. To see all of the kids who were using Seventeen as a soundtrack to them talking about trauma that they’ve overcome or abuse situations.”

“I was so moved by these clips. I was like, ‘How has someone hit us in the heart in just 15 seconds”.

@salah i wish i never met you

♬ Seventeen Going Under – Edit – Sam Fender

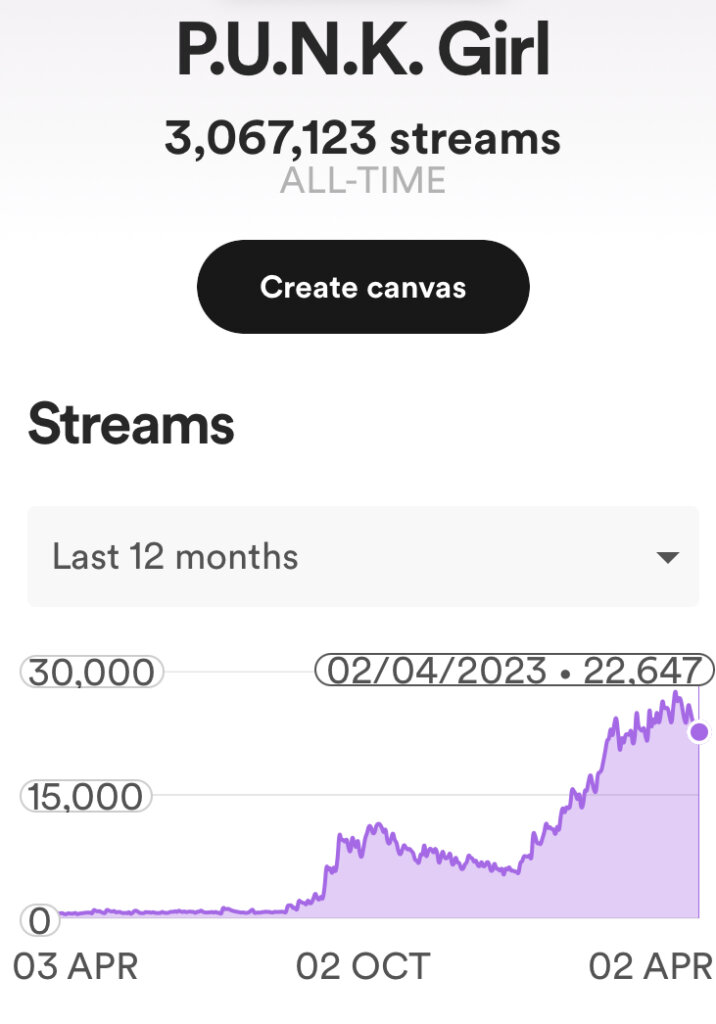

Amelia Fletcher a veteran of indie pop bands like Talulah Gosh and Heavenly who found their song ‘P.U.N.K Girl’blowing up on TikTok with users using it to make their own TikTok memes, it was a big boost for their streaming figures and grew their audience.“It was our teenage daughters who first alerted us to “P.U.N.K. Girl” blowing up on TikTok. They were surprised to discover it on their “For You” feed.” She told us “We investigated further and found there were over 10,000 TikToks that had used it, with some of those having many tens of thousands of ‘likes’.”

@heavenlyindie The original #punkgirl❤️ ♬ P.U.N.K. Girl – Heavenly

“The main meme seems to involve users superimposing the words of the song over a series of scenes of girls – often from a popular TV show like Brooklyn 99 – to create a lesbian narrative. Some of them are really rather great.”

“The impact on Spotify streams has been pretty astonishing. That one song now has over 3 million streams, a massive leap from a year ago. It is clear that the vast majority of our new listeners are young and either female or non-binary. All very exciting for a song that is 30 years old!”

Amelia kindly sent us their social stats to show the audience they were reaching:

There are dangers in judging music on stats alone though. Do followers and likes always equal quality? Can the algorithm be gamed?

Cat Zhang wrote in a Pitchfork piece titled “TikTok is Turning Music Making into a Labyrinthian Game,” “‘Labels’ myopic obsession with TikTok attention has led to some terrible decision-making. Like when the majors come to metaphorical blows over random teenagers who’ve miraculously ridden the algorithm to the top—even if that virality often has more to do with the taste making powers of certain TikTok communities than any given musician’s skill or savvy.” It’s a warning to festivals who book artists off stats or labels who use only stats to sign their artists and don’t use their eyes and ears too.

Plus artists like Halsey and Charli XCX have posted videos expressing frustration at the pressure of being constantly asked to make TikToks by their labels. Earlier this year, Rebecca Lucy Taylor, aka Self Esteem, wrote an opinion piece for the Guardian on why she worries that artists, in particularly female artists are being pressurised to be constantly online and constantly creating “content”.

“But what do you do if sharing parts of yourself isn’t for you? In my 20s I would have blindly believed the authority of labels and management and done anything to grab what might be a ticket to success, with no thought for the consequences it might have later on,” she writes.

“It feels as though the artists decrying TikTok (and the many fans tweeting their dismay about it too) are seen by the industry as being too precious or old-fashioned. But ultimately, the artists that do have a good bash at TikTok will prevail in the ever hungry endless machine, at least for now. It moves without you. So you have no choice“.

Also the royalty system from TikTok is still shrouded in complex arrangements between label, distributor and TikTok and depends on factors, and begs the question should TikTok pay as well as a Spotify when it now allows users to upload entire songs and can eat into streaming numbers?

For example the big viral hit of 2022 Kate Bush’s ‘Running Up That Hill’ (A Deal With God) which blew up thanks to a sync’d appearance on Netflix series Stranger Things, eventually reaching number one in the singles charts in the UK. MBW reported in 2022: “Nearly two months on from the debut of that killer sync, Running Up That Hill remains the top song on Spotify globally. The track, largely in reaction to that sync exploding, has also now been used in at least 2.4 million separate videos on TikTok. According to ChartMetric, just the Top 1,000 most popular of these 2 million-plus videos have, to date, attracted 4.93 billion plays between them. (It’s therefore obviously safe to assume that, beyond the Top 1,000 TikTok videos featuring Running Up That Hill, i.e. taking into account the full 2.4 million+ videos, Kate Bush’s song has been played over 5 billion times on TikTok to date.) Due to there being no revenue share / royalty-based agreement between her distributor (Warner Music Group) and TikTok, Kate Bush is not getting paid for any of those plays.

Outside, that is, of the aforementioned ‘blind check’ sent to Warner by TikTok at a certain point in the past. And only if Warner has paid any of it through to the artist.) Kate Bush’s track has over 5 billion (unpaid) views on TikTok. 5 billion! The song has just over 400 million plays on Spotify, despite being that platform’s global No.1 for weeks. So is TikTok really ‘promoting’ Running Up That Hill? Or is it in fact cannibalizing plays of the song that could otherwise have happened on ‘revenue share’ streaming platforms like Spotify?”

Whether TikTok is for you as an artist is down to personal taste, but it certainly appears to be a tool for promotion if used correctly. There are pitfalls though. If you go viral, you could get a backlash and also remember that TikTok is another means of promotion. The pressure of producing more and more content for social platforms can take away from time spent songwriting or developing as an act. It can also affect mental health. Whilst some are lucky and it can help propel their popularity as an artist or boost their streams, it’s also very hard to go viral if you haven’t got a team working for you who understands how to trend, reach the right influencers or appear in the algorithm or you haven’t the interest yet to start with. Also what is the promotion for if it doesn’t work? Nevertheless, the viral trend of memes of popular songs on Tik Tok and the increasing the connection between artists on social media is only deepening and with the potential rise of AI music, maybe personal connection to songs and lyrics by artists, that reflect our own lives will only become more important?

The tech companies should also invest in the artists and venues that create spaces for these artists to develop in the first place too, the places where artists really get started. As Davyd warns these publicity campaigns for large tech companies that are powered by music, don’t equal fundamental infrastructure and investment in music’s ecosystem that it needs to grow: “We can’t go on pretending that everything is going to be fine for the live music industry by letting TikTok, or Spotify, or YouTube, tell us that success on their platforms equates to long term successful artists with fan bases that can sustain the live music sector. It’s a fool’s game to put all our eggs in the basket of these unproven platforms hoping that artists will spring miraculously from them and start headlining Glastonbury. Live music is a data game. Anyone who books an unproven artist to headline a major festival, an artist who has yet to prove themselves with ticket sales, not clicks, is taking a massive risk with their wallet.“

Whether TikTok is a fad or here to stay, it shows how artists and music can deepen connections with their audience and maybe how music will increasingly shift in how it is consumed and reacted to. According to reports, younger generations are now experiencing music in shorter form with fans consuming short videos on TikTok or playlists, discovery is a strong selling point for TikTok but its also cannabilising listeners on streaming platforms like Spotify or even sales. So whilst it can be a potential avenue for promotion for those who get the lucky golden ticket and a place for music disovery for fans, TikTok needs to be regulated too, as the danger is it will further eat into royalties for artists, which are already poor from streaming platforms. One thing is for sure, TikTok is part of a picture and a reality for many artists promoting their music in 2023, we will be watching how it develops.

@panicshack ‘THE ICK’ @officialrandl pt 2 🤮🥛💀 #theick #icktok #girlband #riotgrrrl #readingfestival #readingandleeds #radio1 #bbcintroducing #fyp ♬ original sound – Panic Shack