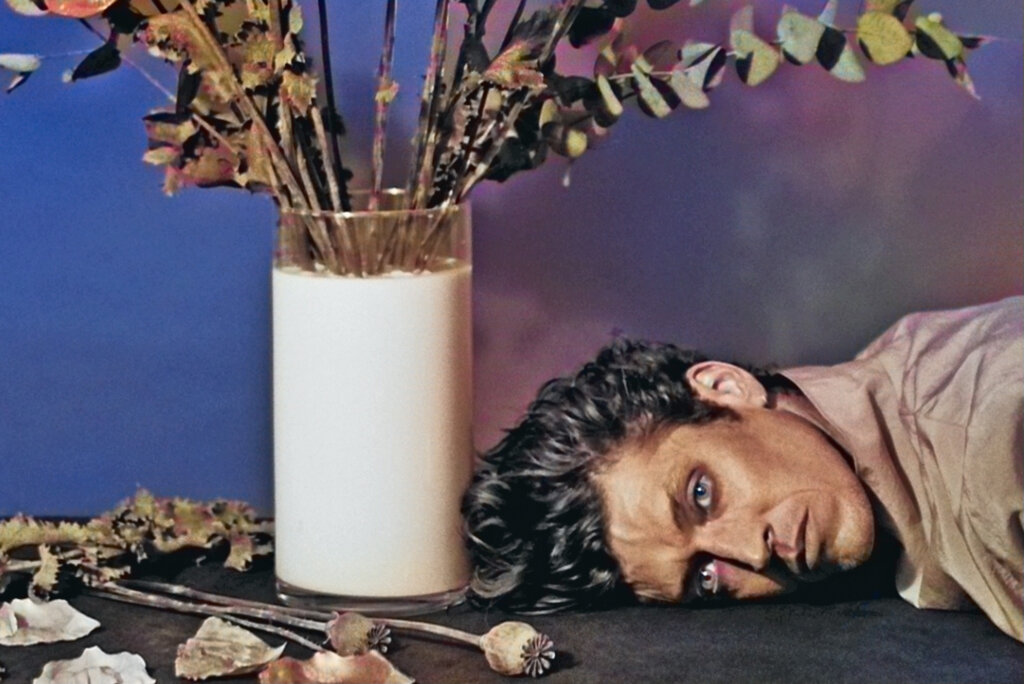

Huw Evans pushes our appointment back by an hour or so to make way for one of a dental check up kind. ‘Did you have anything good done’ seems a fair opening question. The answer is happily no root canal or similar bloodied drama, instead mere rudimentary bits and bobs required on the teeth front. ‘I’m a happy man, considering how much I smoke,’ he jokes, over the phone from his home in Cardiff. How to even start to approach the new H Hawkline record Milk For Flowers, out next week, is a toughie. The record – his fifth – is a tender and raw story of grief, listening to it one feels at times intrusive, as if breaking open a diary of deepest thoughts. Huw’s mother died of cancer four years ago and the album deals with his ongoing bereavement journey into a strange new life and world without her. Is it an over- exaggeration to suggest he bleeds emotionally on the album? It does sound melodramatic when put that way, he admits but concedes ‘I think yeah, I did.’

We don’t need factual detail of events, the record itself does the talking if you let it – and my goodness, you should – the all-encompassing nature of grief leaving no option but to follow the write about what you know path. ‘You have to not think about it too much. Otherwise you just wouldn’t write anything. Half of the best songs ever written wouldn’t have been if the people writing them were worried about how the people who were involved would feel when they listened to them. They’d be crippled by it.’

That’s not to say the album’s a grim and depressing trawl. On the contrary; the piano ballads, country-tinged beauty and naked honesty throws light into the dark. ‘Athens At Night‘ is a bop; and the title song a Northern Soul floor filler in another lifetime. But we’re never far away from the central theme. If tempted to wander or grab an alternative meaning, we’re brought right back, by a phrase, a word, a vocal touch. Despite the inevitable imagery in the lyrics – because it’s still H Hawkline after all, c’mon now – he acknowledges the value of clarity.

‘I just thought, I’m just gonna say the thing. I’m not going to hide behind it or figure out another way of saying it. I’ll say it in the plainest way possible because that’s a lot more powerful. You can just say what happened.‘ Take ‘Mostly‘, in essence a reflection on his own death. A morbid notion perhaps to those free of the consequences of a close bereavement, but such thoughts are natural healthy considerations of making sense of life after loss. To paraphrase Benjamin Franklin, death and taxes are two things we can all rely on. Is Huw questioning his own mortality in the song?

‘Not my mortality, but I’m questioning what do I want to be remembered for. And how would I want to die. Not when, but how would I want it to happen. I think I would want to be on my own. I wouldn’t want to burden anybody else with it, is what I was feeling. And knowing that I’d done right by people. That I’d done all of the things that I wanted to do. Even saying it out loud it feels like such a strange thing to say but it’s a real messy business dying and I think I wouldn’t want anybody else to have to kind of clean it up.’

You’d want it to be somewhere classy, though. Not in a grotty bedsit or anywhere like that.

‘No, in like a really nice hotel!’

I feel like I’m putting you on a psychiatrist couch here, Huw.

‘Talking about the record, it’ll feel like a kind of therapy that I don’t really want to go through! But you know, that’s the nature of the beast.’

In an attempt to take back a sense of autonomy after the emotional chaos, Huw took an ‘every day is an audition at least I choose the soundtrack’ approach. ‘Suppression Street’ on the record would surely thaw the coldest of hearts. ‘I paint my face for everyone I meet’, he sings, navigating his way around a strange new world, member of a club no-one wants to be in. Everything changes post-bereavement, see. Darkens to nightmarish, with new meanings in day to day life and and within cultural consumption.

‘I feel like two really distinct people. This version of me that exists before it happened. But now I’m this new person and I don’t fully understand who I am yet. I’m still trying to figure it out,’ he explains. ‘So I find that what you do is pretend to be that old version of you, the person people recognise and when this new side of you comes out, it be quite shocking for people. Because your viewpoints and everything change quite drastically.

‘In a weird way it can feel a bit like a superpower. You’ve seen, experienced something that gives you this new layer of skin, this new kind of understanding, this new sort of language that you speak. And when you meet other people who’ve been through something similar, you can spot it straight away.’

At home singing to himself or along to a record or song on the radio a realization hit of singing properly, for want of a better word. The subject matter deserved and demanded a straighter approach using the logic that of all the instruments on an album, the voice is the fastest one to connect, communicate. ‘That planted a seed in my head about not being afraid to be vulnerable and to just sing the songs like I meant it basically.’ Huw isn’t a man who enjoys feeling or showing vulnerability, but the choice here was clear. And yet, Mile For Flowers isn’t the first time he’s sung a painful subject head on and truthfully, his live cover of Alex Dingley’s wrenching ‘Lovely Life To Leave’ remains firm in the memory.

‘I’ve never really liked my own singing voice,’ he admits. ‘If you deliberately sing a little bit badly you’re not putting yourself on the line to be judged. I think it’s a Millennial thing of, it’s not cool to try, it’s cooler to sort of be like, oh, you know, yeah, whatever. And I think actually, trying hard to do something and doing it to the best of your abilities is a good thing, you know?’

Listening to piano ballad ‘Like You Do‘ from Huw’s new record, it turns out any initial assumption Milk For Flowers producer and dear friend Cate le Bon sings the falsetto parts is absolutely wrong. It’s all Huw, doing his new thing of feeling exposed, pushing himself vocally. Singing a duet with himself essentially. ‘You can really hear it’s a struggle to sing those high parts!”

Working with trusted musician friends Davey Newington (Boy Azooga) on drums, Paul Jones (Group Listening) on piano, Tim Presley (White Fence, DRINKS, The Fall) on guitar, Stephen Black (Sweet Baboo) and Euan Hinshelwood [(Younghusband, Cate Le Bon) on sax, Harry Bohay (Aldous Hardin) on pedal steel and John Parish (PJ Harvey, Aldous Harding) on bongo – provided a safe and secure environment. Huw and Le Bon have enjoyed a long working relationship, honest exchanges and lively debate unlocking where the record headed. He tells a story of a verbal tussle and digging in of heels over the title song starting life as a slow waltz, the version we enjoy today pop and upbeat. ‘And she was like, “why didn’t you just try it?’ Half of me knew that it was the right thing to do but this other half was holding on to the version I had. I was like, I don’t want to do it, but it does feel good to sing it this way…’ Huw mocks his own stubborness. ‘She’s one of the best producers and I trust her implicitly. I question the things she asked me to do, but I ultimately know that she’s right.’

‘I think the saddest thing you can do sometimes is sing really sad lyrics over a really poppy song. If it’s sad, sad lyrics and you sing it over a waltz and it’s got sad chords, it’s it’s like pitching somebody over the head with a club. It’s like, yeah, we get it, it’s a sad song!’

When writing the album he viewed Neil Young records as close companions almost he played them so damn much, and had George Harrison‘s ‘All Things Must Pass’ on regular rotation. Enjoyed Gram Parsons and Gene Clark at the time too. ‘You really feel it when they’re singing. It’s something else,’ he enthuses and daydreamed early ambitions for the work to be a country record, Americana sensibilities still remaining. You can feel the melancholies and sensitivities, and in some respects H Hawkline 2023 is an embroidery needle and thread away from a Nudie suit. Take the gorgeous ‘I Need Him’. ‘I love country music and there’s nothing better sometimes, because in a country song you just say how you feel, you know? You don’t really dress it up. You just say I’m heartbroken. I’m sad. There isn’t any hiding. It’s all about baring your soul and being really honest about how you feel.‘

On ‘Empty Room’, you pull no punches. The pedal steel adds a magic touch. It was a song that came to him quickly, he says.

‘I hate it when musicians say oh, it just, you know, it came out of nowhere. But it landed on my lap, I sat down noodling about on the piano and the melody came out and then 10 or 15 minutes later, most of the lyrics came out as well. I love that song. I think of all the ones on the record that’s the one I’m happiest with.’

On ‘Athens at Night‘ there’s a reference to Buddy Holly, memories of singing along to ‘Raining In My Heart‘ in the car as a child, the family miming along to the strings. ‘So now I can’t listen to that song and or if I do listen to it, it just it will just – Yeah, it’s tough.’ He was listening to a playlist not long ago and ‘Strangers’ by The Kinks came on. The words resonated. ‘All music sounds different now, to me. In the same way that when you break up with somebody every song that comes on the radio is about you isn’t it and I think that’s that happens after you lose somebody. Every thought, everything takes on new meaning – books, films, music, it’s a nightmare.’

We wind up our conversation reflecting on how he worried over delivering the record to the world. Dreading this side of promotion, he admits, how to present and explain the album threw up a myriad of dilemmas. ‘I’m nervous about talking about it,’ he says simply. Wary of exploiting confidences, feelings, and his mother’s memory, to push his album.‘Like Britain’s Got Talent,’ he adds in all seriousness. H Hawkline giving it all sandwiched between a pirouetting dog and wholesome rock choirs, is wonderfully absurd and strangely appealing. Of his experience these past few years he wonders, how do you talk about any of it without talking about it all. ‘I feel like I’m performing this bizarre, weird dance and in my mind nobody knows what I’m dancing about, but everyone’s hey we know what you’re dancing about. And I’m no, I’m doing this thing, skirting around it.’ But do you know what, Huw? We do know, and we know you know we know. And it’s ok. You dance on.

Milk For Flowers, is out on Heavenly Recordings on 10 March 2023.

H Hawkline headline tour:

10.03 Cardiff, Clwb Ifor Bach

11.03 Manchester, YES

12.03 Dublin, Workman’s Club

13.03 Glasgow, Hug & Pint

14.03 Leeds, Brudenell Social Club

15.03 Brighton, The Hope & Ruin

16.03 London, Omeara

17.03 Bristol, Rough Trade

Supporting Aldous Harding:

16.04 Brighton, Dome

18.04 Dublin, National Concert Hall

20.04 Manchester, Albert Hall

21.04 Edinburgh, Assembly Room

22.04 Newcastle, Gateshead

24.04 Bristol, O2 Academy

25.04 Cardiff, Tramshed

26.04 Norwich, Waterfront

28.04 London, Barbican Centre

29.04 London, Barbican Centre