noun: books, magazine, films etc. with no artistic value that describe or show sexual acts or naked people in a way that is intended to be sexually exciting

The Cambridge Dictionary

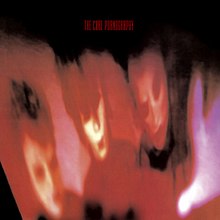

The Cure‘s fourth album, Pornography, was released in May 1982. In terms of human feeling, it is hard to think of an album that is more naked and showing the depths of despair to the point of nihilism.

As someone who fell, hard, for The Cure as a fourteen year old in the early nineties, and never looked back, it was bemusing that people would dismiss the band as being depressing and miserable and then cite the likes of their upbeat pop singles as if to back up their claim. This album, brilliant as it is, is most definitely not an album for the faint hearted.

Was it an un-entirely expected bleak album? For those who were growing with the band, rather than looking back, perhaps not. The closing, title track of their Three Imaginary Boys showed a different, darker side to the band. The release of Seventeen Seconds and Faith, each progressively darker, over the next couple of years were a quantum leap, as much as that of Radiohead on their first four albums well over a decade later. Perhaps the closest glimpse was the in-between days, sorry, single ‘Charlotte Sometimes‘ released in late 1981. Both it and the percussive instrumental b-side ‘Splintered In Her Head‘ showed just how dark things were getting in so many ways in the Cure’s world. ‘Splintered‘ particularly was hallucinatory, the kind of song that if you closed your eyes to, the nightmares you might experience are way too close to reality.

Less than four years since their debut on vinyl, the Albert Camus-referencing ‘Killing An Arab‘ single, the band’s line-up had shown that it might be ‘fluid,’ to put it mildly, but also that they were capable of coming together to make one hell of a band record. It took place at RAK studios in London’s St. John’s Wood early in 1982 whilst Kim Wilde was making her second album Select, a rather different album, at the same studios.

Having worked with producer Mike Hedges on the previous two albums, the band were looking to work with someone new on their next album. According to then-drummer Lol Tolhurst‘s autobiography Cured: The Tale Of Two Imaginary Boys, at one stage, the band had met with legendary Krautrock producer Conny Plank at their label Fiction’s offices, but ended working with Phil Thornalley. The latter would end up being their bass player for 18 months, although that’s a different chapter of the band’s story entirely. Frontman and guitarist Robert Smith recalled of Thornalley in the sleevenotes to the 2005 re-issue of the album that the reason they went with their new producer was because of his engineering work with the Psychedelic Furs, particularly their second album Talk Talk Talk, released in 1981.

Thornalley may well have been left wondering what on earth he had got himself involved in. Those sleevenotes again suggest that this was a world where normal rules in life no longer applied, never mind a recording studio. Numerous sources have suggested that there was a lot of alcohol and drugs flying around, and the band had started building rooms in the studio out of ‘cans, boxes, newspapers and towels.’ This strangeness extended to the music. Smith remembered: ‘I remember there was one particularly long row over a guitar sound that [Hedges] didn’t like. He thought that it was horrible and couldn’t see that that was a good thing!”

Pornography in its original state clocks in at around forty-three minutes. While in the days of cassette walkmans and c90s the length meant it fitted comfortably on one side of a tape, it’s debatable whether it would have been possible to for the band to make more music in that vein or for listeners to deal with it, at least on first hearing. Perhaps given that Smith spoke of wanting to make ‘the ultimate fuck off record” and was thinking at the time that this might be the last Cure album (something that old Cure fans will be familiar with is the claim that each album or tour is the last, even as the gaps between records over the following decades have got progressively longer and longer).

The album opens with the brilliant, bleak ‘One Hundred Years.’ Tolhurst’s militaristic drumming, Simon Gallup‘s ominous bass and Smith’s wailing guitar. And that’s before the vocals kick in. ‘It doesn’t matter if we all die‘ are the first words we hear on the album. A whole host of terrifying images unfold. Is this one nightmare or a snapshot of many? ‘Stroking your hair as the patriots are shot…creeping up the stairs in the dark, waiting for the death blow...’ David Bowie had spoken of using William Burroughs-style cutup techniques to write songs and it’s like the band had written down their nightmares to take things to a logical, extreme conclusion. While the band never explicitly suggest suicide (thankfully), it’s an album that comes from a frighteningly dark place. ‘Years‘ and the third track ‘The Hanging Garden‘ are the only tracks that have much pace about them, it’s the slower pace overall that makes this album more ominous.

‘A Short Term Effect‘ suggests that the short term thing might just be this mortal coil itself, with more than one song on the album featuring lyrics about animals dying. Is this impending nuclear holocaust or the end of the world as described in the book of revelation? ‘Siamese Twins,’ the closing song on the first side sees relationships with those who were once (presumably) close break down to less than nothing:

‘Leave me to die

You won’t remember my voice

I walked away and grew old

You never talk, we never smile

I scream, you’re nothing

I don’t need you any more

You’re nothing‘

It’s not even the bleakest song on the album.

Released in 1982 just before CDs and CD players were released commercially, one wonders if turning over from sides 1 and 2 gave listeners a bit of a break. The second half of the record is even bleaker than the first. Dante’s description of the ninth circle of hell was that it was not burning but actually freezing, and certainly the first side seems warmer by comparison. ‘The Figurehead‘ has those militaristic drums again, but they’re so slow, like a funeral in a totalitarian state where everything is grey. The disconnect is becoming ever more so, ‘I laughed in the mirror for the first time in a year‘ like a reincarnation of Miss Haversham. It’s the final repeated line ‘I will never be clean again’ – as if the Macbeths still wonder the earth seeking to rid their hands of the blood.

‘A Strange Day‘ might just be the best song on the album. In many ways it seems like a nightmare drawing on aspects of Greek mythology: ‘Give me your eyes that I might see/

The blind man kissing my hands‘ evokes the Gorgons’ sisters The Graeae, but what is witnessed is the end of well, ‘everything is gone forever‘. ‘Cold‘ opens with a six note riff played by Smith on the ‘cello before organ and keyboards kick in to produce music that is not so much a chill down your spine, as a place that’s bloody freezing (and that’s not just because I’m trying to avoid putting the central heating on). ‘Your name like ice/into my heart.’

The title track closes this dark, dark album. It is not only the bleakest track on the album, but possibly one of the bleakest things ever recorded, it feels like the lowest place it is possible to reach in this life or the next, the ninth circle at absolute zero. The distorted voices give way to more of that militaristic drumming, bringing the album around full circle. Lyrically, we are at the end -‘one more day today and I’ll kill you/a desire for flesh and real blood.‘ Yet is there the slightest bit of hope, even a sly wink – ‘I must fight this sickness, find a cure?’

Yet for all the darkness, it’s an amazing place to behold. We watch horror films for the pleasure of being scared, and watch them again, even if we know that Carrie’s hand will shoot out of the grave, or that all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. In literature, Jonathan Harker must have had doubts about the castle in Transylvania, and surely Dr. Frankenstein must have had second thoughts about what he was doing? Yet the results are terrible…but great. It’s the same with Pornography. It may be born of a dark place, but this is art, Jim, just not as we knew it.

While it is hard to think of an album like this being a hit, it actually saw the Cure making commercial inroads. In terms of success, it is perhaps surprising that it became the Cure’s first album to debut in the UK album chart in the top ten, peaking at a respectable no.8. ‘The Hanging Garden‘ was their second top 40 hit single, peaking at no.34. Perhaps less surprisingly, three tracks made John Peel’s annual Festive Fifty for 1982- ‘ The Hanging Garden,’ ‘The Figurehead‘ and ‘A Strange Day‘ reached positions 25, 28 and 33 respectively.

It had a mixed critical reaction, even decades after its release. Dave Hill in the NME described it as ‘a very big, very harrowing achievement.’ Adam Sweeting of Melody Maker described it as: “It’s downhill all the way, into ever-darkening shadow’ while Sounds‘ Dave McCullough felt that though there was ‘a genuine talent still at work…the music too cluttered a backing for Smith’s well-intended observance.’ Into the 21st century, Uncut called it ‘a masterpiece of claustrophobic self-loathing‘ awarding it five stars, but The Guardian sniffily dismissed it as ‘one of the ugliest long-players ever conceived.’

And what of its legacy? One of rock’s most extreme records? Its heritage might be said include Joy Division‘s bleak but brilliant two studio albums Unknown Pleasures and Closer, and Nico‘s The Marble Index and Desertshore, along with the likes of Industrial acts like Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire. Smith told Select magazine back in 1991 this and Disintegration tended to be the favourite albums of Cure fans who’d thought about it a bit more.

The tour was a nightmare by all accounts, with Gallup being fired at the end and Smith and Tolhurst taking a complete 180 degree turn with where they would go next. But this is truly a remarkable record. In the words of Tolhurst, who describes it as his favourite Cure album: ‘I really value Pornography and unlike the earlier material, I wouldn’t change a damn thing. Everything is exactly as it should be.’