“I don’t think I ever realised that,” Don McLean told presenter Elijah Griffith when asked for his feelings about ‘American Pie‘ now being recognised as one of the greatest songs of all time, and one of the most influential albums from the 70s.

“I was just very excited about the idea of the song, and I was in a pretty big struggle to get the song recorded the way I heard it… That was all I wanted to do,” he told the Homegrown Happy Hour Podcast, before admitting that, “I really didn’t know anything about hit records, because I’d never had one.”

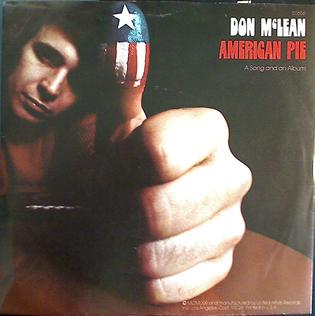

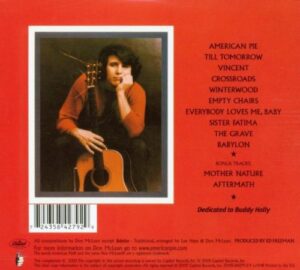

Recorded at New York’s famous The Record Plant studio over the May and June of ’71, the album, American Pie, was Don McLean’s second studio release. It produced two hit singles and helped to break down the boundaries of accepted musical genres of the time – merging Folk, Country and Rock n’ Roll – before receiving worldwide critical acclaim and making Mclean a household name. As he would admit, fifty years later, American Pie changed his life.

The song itself was dedicated to Mclean’s musical hero Buddy Holly, set around the devastating plane crash that claimed the lives of Holly, Richie Valens and The Big Bopper one cold February evening in 1959: in Mclean’s opinion, “the day the music died”. The album would lead to conservative America’s children openly questioning their country’s civility and morality, and help herald in the beginnings of a modern cynical America we see so widely today.

“To me, when Kennedy was killed, all bets were off… It was the beginning of Americans being in doubt about what they believed in, and who they were,” the singer-songwriter revealed to television anchor, Dan Rather.

“It was about an America that was coming apart at the seams,” he added in Classic Rock magazine. “I wanted to connect with the parts of America that mattered to me.”

At the beginning of 1971, Don McLean was a 25 year-old struggling artist residing in downtown New York, trying desperately to come up with a fresh collection of new songs that he hoped would follow up on the release of his debut L.P. Tapestry, which had received good reviews from some very notable music magazines and renowned critics, but achieved very little in the way of radio airtime or commercial success: a disheartened Mclean now fearful that no one would take any notice of what it was he was trying to say, and terrified that he had fallen through the cracks as differing styles and genres rapidly emerged from what was left in the debris of the sixties; a new breed of bold singer-songwriters, male and female, seemingly willing to confess and reveal all, and beginning to take wing and soar into the public consciousness. Americana had come of age.

‘American Pie‘, the single that was to reach number 2 in the UK charts, was originally intended to be an acoustic song, and was one of the last to be completed in time for inclusion on the album that would eventually bear its name.

“American Pie is a death song, really,” McLean told Uncut. “Friends of mine who’d died in Vietnam were being brought back. There were flag-draped coffins, assassinations. Rock’n’roll and Buddy Holly had saved my mortal soul, as the song says. Holly’s plane crash in 1959 foreshadowed a series of deaths, from my father’s two years later when I was 15, which shattered my life, through to Kennedy’s. I came from a conservative, white middle-class background, and all this destroyed my belief in everything I had been taught.”

The song was meant to be just McLean’s mourn-filled voice delivering its haunted and remorseful words, set back against the powerful regretfulness that comes from a gently strummed guitar: a harking back to an innocence long lost. And that was exactly how it was originally presented to producer Ed Freeman on the original homemade demos.

“I thought that it was incredibly heart-wrenching and emotionally moving,” Freeman recalled later for a U.S. radio interview. “I felt that it was just missing something… The emphasis perhaps?”

“He had total control,” Mclean readily admits, explaining the input Ed Freeman had and the ideas he was to come up with as the recording sessions went on, especially in suggesting the musicians that he felt would be suitable, and that Mclean would like and trust enough to be able to work with.

“I knew what I wanted and what I didn’t like, and Ed was great at finding the right people.” Great at finding piano players for instance. “He knew a lot of piano players,” Mclean laughs. “He knew them all, and we had some great ones…” Like Paul Griffin, who had worked with Dylan, The Isley Brothers and Van Morrison, and whose distinctive, colourful style really brought the eight and a half minute track to life.

“Some of the rehearsals were better than the finished tracks,” Mclean is happy to admit in interviews now though, as he celebrates his masterpiece’s special anniversary, “looser”, he suggests, although producer and songwriter together were to spend ages trying to get the musicians to play the songs correctly, to capture the way they sounded when rolling about Mclean’s mind.

“Everything was written on my guitar,” he told Joe Chambers, the founder of the Musicians Hall Of Fame. “And then I realised that I was at a stage, a point, where I could have anything I wanted. I could have strings. I could have vast arrangements… But I was anxious not to overdo things. Complicate them. Ruin them.”

“I love Phil Spector,” he added, referring to the famed producer’s recent work with both Lennon and Harrison, “but I didn’t want to do that.” He didn’t want to replicate that, “wall of sound” effect, he insists.

The first track written for his new album, at least to Mclean’s recollection much later, was ‘Vincent‘. “Ticked over and thought out,” he said, sped up and slowed down and rewritten, over and over, “til everything was exactly how I had heard it, over all that time.” Mclean had carried all these events and all their residue feelings with him for a long, long time, Freeman explained, “and they had a deep emotional impact on him”, so here he was to finally find an outlet for them, allow them a voice, at long, long last. The guitar was ever important though; the soft duet, the accompanying guide, the comforting foil to Mclean’s long lament to a country lost.

As he told The Daily Telegraph: “I was sitting on the veranda one morning, reading a biography of Van Gogh, and suddenly I knew I had to write a song arguing that he wasn’t crazy. He had an illness and so did his brother Theo. This makes it different, in my mind, to the garden variety of ‘crazy’ – because he was rejected by a woman… So I sat down with a print of Starry Night and wrote the lyrics out on a paper bag.”

Every song chosen for final inclusion on the album is conflicted with the sense of love and loss, “just to differing intents and purposes,” according to Freeman. “They all mean something… Are all deeply personal to him,” he insisted, “reminding him of those moments, the most influential moments of his life that have always accompanied him in some form or another.”

American Pie was crafted very carefully, layer placed deliberately upon layer, making it sound deceivingly simplistic, but yet thought-provoking and easily relatable, accessible on so many levels, although the title it was given, merely “easy listening”, derides it, and belittles its effect on a nation’s psyche through the years. At that time, the beginning of a new decade, the confessional singer-songwriter was still something new, but American Pie is still, perhaps, the most perfect example of voice and guitar in wrenching harmony with its highly personal subject matter of loss, regret and remorse, and all coloured by those unfettered keys and longing strings studiously arranged by Freeman.

‘Everybody Loves Me, Baby‘ is a rock and roll song adrift the sea of Folk, or what would now be pigeon-holed as Alternative Country, so powerful in its serene surroundings. A bitter, angry song to some? Or something almost approaching flippant, perhaps even throwaway, ’til you really chance to listen to it, absorb the lyrics in full, or even in snippets. Deceptively drawing you in.

It still sounds fresh. American Pie is still relevant, these fifty years later. All the songs these memories provoked still reside, its subject matter from a bygone era still catch the imagination, and still tinge emotions with the burden of sadness born of frustration, as ‘Babylon‘ comes to a close with its almost religious-like chant or mantra. The long decline in virtue and of morals, and a wishful regaling of times passed, regretfully irretrievable, no matter how hard we try or how much we repent.

“If you’ve ever cried because of a rock & roll band or album,” Lester Bangs wrote for Rolling Stone, “or lain awake nights wondering or sat up talking through the dawn about Our Music and what it all means and where it’s all going and why, if you’ve ever kicked off your shoes to dance or wished you had the chance, if you ever believed in Rock & Roll, you’ve got to have this album.”

“We made a really good record,” Mclean proudly admits to Joe Chambers. “A really good album… If we didn’t have that we wouldn’t be talking about it now.”

American Pie was released in the U.K. in April, 1972