On Sunday night a wonderful thing happened. A talented man won an award for a job he did well. OK. Nothing earth shattering there… Until I tell you this man is Troy Kotsur. He is the first deaf actor to ever win a Bafta, for his dazzling performance in CODA, and only the second deaf person to ever be nominated for an Oscar. The first was the ever perfect Marlee Matlin, who also stars alongside Kotsur in ‘CODA’, who won best actress in 1987 for her performance in ‘Children of a Lesser God’.

You did it, @TroyKotsur! Now it's time to celebrate your first BAFTA win (and also make that James Bond idea happen) ❤️ #EEBAFTAs pic.twitter.com/6HgiGAALFJ

— BAFTA (@BAFTA) March 13, 2022

CODA is an English-Language adaptation of a French film ‘La Famille Bélier’. Written and directed by Sian Heder, CODA is an acronym for “Children Of Deaf Adults” and our eponymous heroine is Ruby who at 17 is the only hearing member of her family. She is torn between helping her family’s struggling fishing business in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and finding joy in her prodigious singing talent, a talent of course that cannot be fully appreciated sonically by her family. What is crucially different about the original film and this remake is that in the French version, many of the actors playing deaf people weren’t actually deaf. For Heder it was very important for reasons of both representation and authenticity that the deaf people in her film be played by deaf actors, and that silences in the film not be filled by music and sound that wouldn’t be experienced diegetically.

In an article with The Guardian, when talking of CODA, Kotsur said “The film has had an incredible impact on deaf, hard-of-hearing and disabled people,[…] Now they’re able to really see their identity, their experience being shown on screen.” Half the dialogue of the film is in American Sign Language (ASL), a brave decision that risked the film ever getting made. Heder: “It was heartbreaking on one hand and on the other hand it felt like that other version of the movie should not exist”. Representation is the key issue and word here. Whilst deafness is not necessarily a disability, it is a difference that exists between people that can become a site of conflict and stigma. For the purpose of this article and the way actors who are deaf are treated it becomes very much like other disabilities or conditions under-represented in popular culture.

As with the film’s original text, for a long time disabled roles have been played by simply anyone who the film company wanted to cast, with little thought to accurate representation. These meagre award statistics are so meaningful for the deaf community and also disability rights activists. Kotsur’s win becomes more poignant when put into the canon of the moving picture. Screenwriter Jack Thorne calls disability the “forgotten diversity” and this really is true in life as much as it is in film as many disabled people and activists will tell you. He says he has seen many actors being told they are simply “too disabled” for certain roles. So much parity exists for so many other minority groups that doesn’t exist for disabled people – marriage (yes, really), employment, simple access into buildings. Just as with other diversity challenges, fighting for representation on screen has been even more challenging than in real life at times. The general public, whoever film companies believe them to be, have apparently wanted a non-challenging view of “real life” which traditionally meant no gay, ethnically diverse or disabled people. So much work has had to happen, like a swan paddling manically underwater.

If we look back over the years at films that famously include a disabled character most are played by an able-bodied actor. A recent Nielsen study completed in 2021 found that 95% of disabled parts are performed by able-bodied actors. Two of the best known examples being ‘My Left Foot’ with Daniel Day-Lewis and ‘Rain Man’ with Dustin Hoffman. Daniel Day-Lewis won an Academy Award for his role portraying a man with cerebral palsy. It is generally accepted now that one of the reasons many actors playing these kinds of roles may not necessarily be for the power of the screenplay or story but because it was considered impressive how successfully the actors “imitate” the disability, which is of course insulting and ableist. Maysoon Zayid, a disabled actor with cerebral palsy known for her recurring role in General Hospital believes: “In my opinion, in order to be an incredible or even credible cast, any visibly disabled roles must be played by actors who actually have that disability. It is offensive, inauthentic, and cartoonish to have non-disabled actors play disabled on screen”.

Another film criticised for its critical acclaim in this department is The Theory of Everything. Starring Eddie Redmayne as Stephen Hawking, renowned physicist who suffered from ALS, it is adapted from the book written by his ex-wife about their romance at Cambridge University. Not only was it disappointing to see Redmayne in this role, but the depiction of disability itself and Hawkings’ daily experience of life as shown in the film was heavily criticised as being stereotyped visually and thematically. For example, how Hawking was shown to feel in his wheelchair and interact with his chair and the world around him was semantically stereotyped. It was the same kind of visual language with wheelchairs and wheelchair users we had seen before, the same frustration and dreaming of “freedom” and nothing new was offered. As much as I am ever loathe to credit Ricky Gervais with being right, one of his most accurate observations comes from Kate Winslet’s turn in Extras “You are guaranteed an Oscar if you play a mental.” For years this was true of actors taking on particularly “difficult” acting roles as an able-bodied person trying to embody the concept of living with a disability as actors have – whilst not necessarily won Oscars, but tended to be in with a chance of critical acclaim.

It seems careless to write about this subject without mentioning one of the worst culprits ever made in recent years in terms of horrifically insulting representation, mainly because it also became part of a “chicklit” fiction movement that was deeply troubling: Me Before You (2016). Adapted from the Jojo Moyes’ novel of the same name and follows Louisa (Emilia Clarke) as she is hired as a carer for Will (Sam Claflin), formerly a successful banker now a tetraplegic after an extreme sports accident.

Their relationship is tender, inspiring, total rom-com meet-cute amazing. But of course, Will wants to end his life with his mega-banking-bucks at Dignitas in Switzerland because being alive and disabled is simply not worth doing, he is apparently a drain on Louisa. The issue? It is not that disabled people or any people don’t ever feel suicidal and it is not therefore authentic to show this in a film, or that there aren’t genuine cases and ethical pleas for euthanasia but Me Before You just seemed to pour a steaming pile of smelly stuff on everyone actually trying to get on, or, shock horror, daring to enjoy life whilst being disabled. It discounted us all as worthless. As I mentioned, for those who seemed to find the tragic romance as inspiring and Will’s ultimate sacrifice as gallant, no one understood that love can accommodate disability and so much more, more fiction like this seemed to spring up like parasites.

In itself having anyone trying to imagine life with a disability is of course a good thing, empathy and all that, but, if you can have disabled actors take up these roles, that is far better and also leads to more authentic performances. There has been huge efforts for disabled actors to be placed in disabled roles and for there to be any disabled roles at all, for the communities we see on our screens to reflect our own communities. This has often felt like a losing battle, however, as Dominick Evans, a disabled film-maker and activist notes: “We’re looking at representation [in films] as low as 1% for a population that is around 20% of the world.” For the 1% representation roles that do exist then, there is a battle for the chance for disabled actors to be considered for these parts. This is what Kotsur was celebrating on Sunday night. It is similar to the same fight that has gone on in the LGBTQ+ community.

Ironically one of the genres where disability is least successfully represented is reality television. In all our reality TV formats, be they competition or dating shows, physical prowess is demanded in such hyper-superficial terms. Even the shows that seemingly concentrate on brain power end up demanding physical traits for “entertainment” value – think skill based shows like cookery shows, or The Apprentice where no exceptions can be made to “The Formula”. The only reality TV shows that allow disabled people tend to be contained formats such as ‘The Undateables’ or ‘Love on the Spectrum’. Many celebrate these shows as demi-documentaries, feeling them to be true portrayals or social commentaries, but they are pure fetish freak show material however you dress it up. For me this is representative of society and our entrenched stigma. We can almost cope with disability when it is carefully scripted, contained in fiction. But we cannot get close to letting it loose.

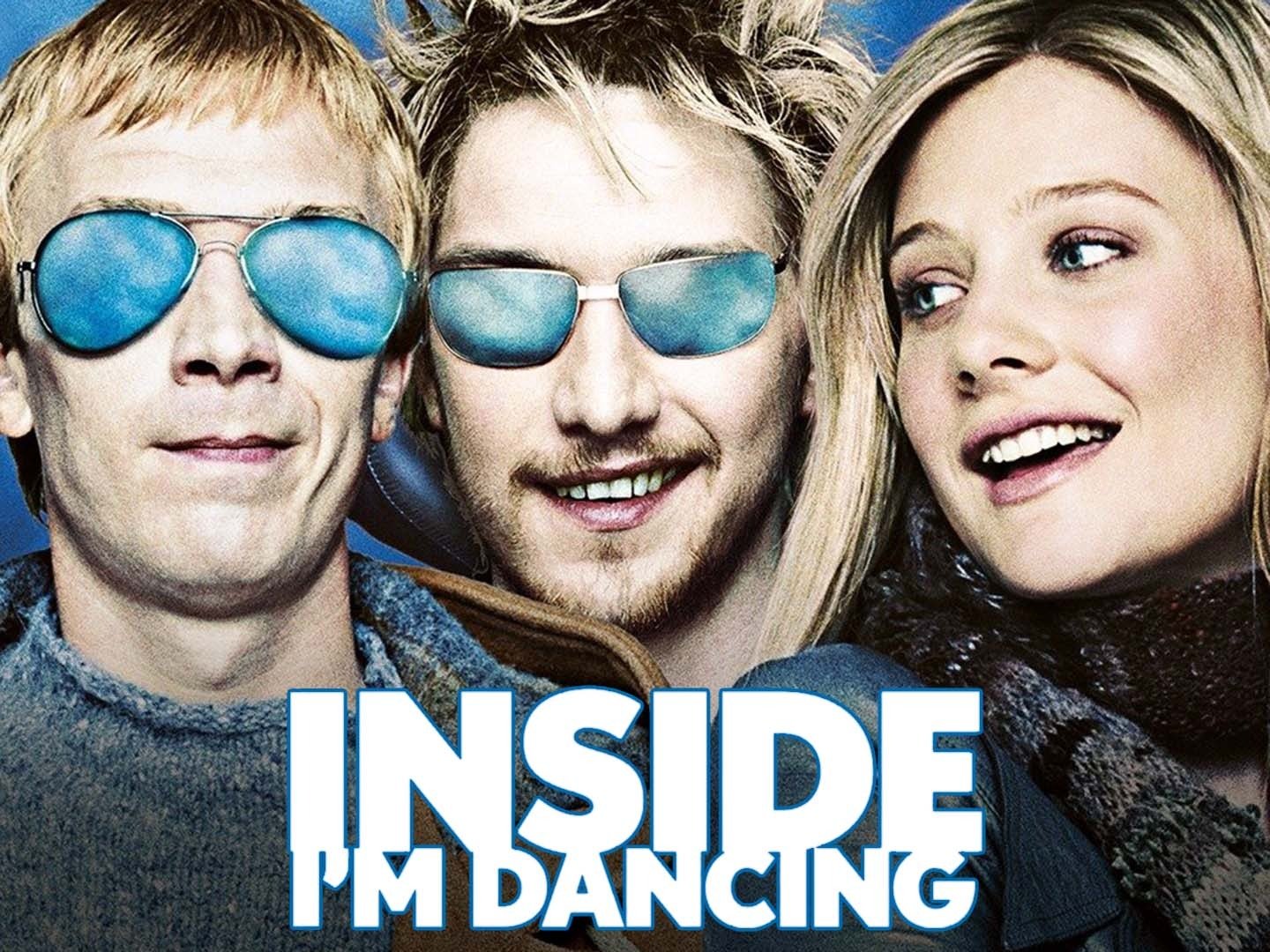

One of My favourite films that portrays life with disability accurately and sensitively ironically doesn’t have disabled actors and so does prove that able bodied actors can sensitively portray disabled people. But. It has something else that is missing in these other films we mentioned such as My Left Foot and Rain Man where disabled people are played by able bodied actors. That is it does not have a singular disabled person as the centre of the story but instead concedes such a thing as community can exist, a multiplicity, different characters even of disabled people. This shouldn’t be so groundbreaking. But it is. ‘Inside I’m Dancing‘ (Alternative Title Rory O’Shea Was Here) (2004) has been strangely popular with disabled audiences largely because of its ability to recognise the humanism many films ignore.

It stars James McAvoy and Steven Robertson as Rory and Michael, two young lads forced into institutionalisation because of their disabilities but shows us their need and desire for life and individuality within these confines – basically it simply shows lads being lads who happen to also be disabled. This is something Dominick Evans writes about as being crucial in the progression of portrayals: “Why can’t there be multiple disabled characters who are different races / ethnicities, genders / gender identities, and sexual orientations?” Inside I’m Dancing was a step towards this more accurate representation. This shouldn’t be seen as progressiveness. But the fact that the film shows the use of hoists and mobility aids, yet the fact that these characters want to party and be out in the world, not left to live segregated in an institution as is expected of them felt so refreshing, depressingly refreshing, when I first watched it. This leads to the central contradiction of the film, however. How can a film with seemingly such “progressive” aesthetics not dedicate itself to true authenticity with their actors? Perhaps this is a reflection of how hard it is to make these types of films, it was too hard to get it made without “a name” in one of the roles, even though McAvoy was a relatively small fish back in 2004 the fact is there are more famous able-bodied actors than disabled ones.

We are seeing more disabilities accepted fluidly into our linguistics of daily life, however, and therefore into our TV and film too. It is noted by Disability Rights UK that with the hugely popular TV shows such as Monk, The Sopranos, Doc Martin and Homeland, all the protagonists suffer from very life-changing mental health issues that would have been ignored, undiagnosed, undiscussed in TV shows made in earlier decades and certainly not made into plot points. Whether their uses in the narrative are always positive portrayals or not is a difficult discussion and complex to unravel and I think in the case of these shows in particular the point to be made is that the disorders are being made visible and we have language for them in ways we previously didn’t.

The final taboo of all disability stigma is of course, sexuality. It is hugely surprising and liberating that we see a wheelchair bound ‘Lieutenant Dan’ having fun with a woman in Forrest Gump but this is a transactional encounter and very non intimate in mood. We still lack open dialogue about true attraction in disabled culture. It is either fetishised or it has to still be kept as “other”, for example in dating shows such at C4’s The Undateables or Love on The Spectrum (for a more positive representation of neurodivergence try Atypical). In Leslie Harris’ fantastically insightful essay ‘Disabled Sex and the Movies’, Disability Studies Quarterly 2002, they outline a very good basic guide to the standard visual semantics we are used to seeing in film in relation to disability. They discuss how it has been established to use long, lingering very close up shots on the wheels of wheelchairs to solicit empathy and emotion. They then talk about the way that most films use sexuality poorly, showing women as submissive and weak, if sexual beings at all, with few films such as Peter Medak‘s 1992 film ‘Romeo Is Bleeding’ striving to experiment with showing women in positions of sexual power whilst also having physical disabilities. In the case of Romeo Is Bleeding one of our central characters Demarkov has her arm amputated yet remains a being of sexual desire and also sexual power.

What seems to be pretty universally agreed upon and academically sound is that the majority of narratives containing a disabled character use them purely to serve a purpose; to further a depressing or redemptive trope. They have been part of plots to do with the very point of the film or TV show and are either there to be inspirational, saved, selfish, innocent and childlike, or in extreme circumstances ready to end their lives because of their disability and for that reason enlightened. It is rare that we just get a person with a disability who can function in the story for other reasons and aspects of their personality. A really good example of a TV character with a disability for no other reason – ie “good” or positive representation, played by an actor with an actual disability is RJ Mitte playing Walt Junior in ‘Breaking Bad’. This is the kind of authentic representation most disabled people seem to be able to agree on as being something real that they would like to see more of. Another positive example if you want a go-to for weekend viewing is the wonderful Pixar animation ‘Luca‘. It features a character who lives with limb difference without making it a defining characteristic. This also obviously opens the conversation of inclusion and diversity being positively visible in children’s fiction and narratives. It has long been accepted that this is an important developmental issue for societal growth.

There is change happening, though, it seems. Whilst at times it feels stagnant, more “firsts” are occuring. This month on March 18 Amazon Prime releases a new Bollywood film Jalsa. It is hoping to follow in the footsteps of CODA in terms of diversity as it boasts being the first film originating from Bollywood to feature a disabled actor in a disabled role. Starring Surya Kasibhatla – a Texas based actor born with Cerebral Palsy it strives for a huge movement within the world’s largest film industry.

Obviously CODA is not subtle in its depiction of what it is like to experience life without sound, nor should it be. Deafness and deaf culture is front and centre of the film but that is OK because of the extreme sensitivity with which it has been done. Because of using ASL for most of the film, deaf actors and the genius sound editing, it’s an authentic representation that has even had other actors learning ASL to speak to Troy Kotsur. This interaction, inclusivity, naturalisation is true community and visibility and it is why this week has felt like a triumph for many people.

Troy Kotsur and Andrew Garfield sign on the #SpiritAwards red carpet. https://t.co/kBDEmR38iD pic.twitter.com/rQVfc8TBUr

— Variety (@Variety) March 7, 2022