Just a mortal with potential of a superman!

“Albums in general back then had a couple of great songs, three or four good songs,” Rick Wakeman told MOJO magazine, “and then you’d have three or four fillers that nobody ever played. Hunky Dory,” he insists, “was ALL great. It was just a matter of which song was greater. And that’s what made it unique.”

At the start of 1971, David Bowie’s career seemed over before it had really begun. At the turn of the year, a year which would later see Marc Bolan begin to scale dizzying heights with T. Rex and set in motion a movement glammed up in eye-liner and glitter, it would appear to most music journalists and onlookers that the singer with the “flopsy” hair and the “bipperty-bopperty hat”, was deigned to be remembered by a curious few, to be labelled and shelved as just another wannabe in a now long, long list of one-hit wonders: the folksy singer of some distantly recalled 60’s novelty single that had been used to accompany all the grainy footage that had been beamed back from a, then, still seemingly faraway moon. Once all that excitement had worn off however, plain old David Jones slunk back to the shadows, consigned to barely a line in the annal of rock. Or so it seemed.

After all, his last album, 1970’s dark, menacing and brooding, The Man Who Sold The World, with its guitar rock edge and sinister foreboding of all-consuming religion and inevitable slide into madness, had largely been ignored by a record buying public still heartbroken over the acrimonious dissolution of The Beatles, and despite all the initially warm reviews that acclaimed it as, “surprisingly excellent”, (Melody Maker), and “rather hysterical”, (N.M.E.).

Even a flamboyant stage appearance as The Hype, a small yet busy stage suddenly full to bursting with various superheroes all cavorting about in individually crafted, and lavishly outlandish homemade costumes, failed to spark the imagination, instead deriving little more than a passing moment of bewildered curiosity. Now of course, we know that Bowie was simply “ahead of his time”, and, with Bolan watching his friend from the stage sidelines, that the seeds of Glam Rock had been sewn.

At 42 Southend Road, however, in Flat 7 of what we are told was once a lavish and sprawling Haddon Hall, the 24 year-old sits at a grand piano, or strums odd and peculiar chords on an acoustic 12 string guitar, pausing to quickly pen strange fragmented lyrics all through his notebook or to compose weird melodies that went off in odd and bizarre tangents. As drummer Mick “Woody” Woodmansey recalls for MOJO magazine: “You’d hear him piecing things together. We’d hear, ‘Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow’ coming through the butler’s hatch,” Woody and guitarist Mick Ronson would “be there going, ‘Fucking hell that’s a bit weird, innit?’ You know, ‘Lennon’s on sale again’ and ‘the mice in their million hordes’. ‘What the fuck? Pass the toast.’”

Every now and then Bowie would quickly usher them into his apartment and play them the latest, and still as yet, untitled song he’d just written, just him and his 12 string, or just him at the piano, looking to them for an immediate reaction.

As Rick Wakeman explained on Jonathan Ross’s radio show, ”I went in there [Haddon Hall] and there was a big gallery and I went upstairs and there was a grand piano and he’d got his old battered 12 string. He said ‘I want to play you some songs, I want you to learn them and then I want you to play them from a piano point of view… I want you to play them in the style you play and I will make the band and everything work round it’, and one by one he just kept playing these songs like, you know, Life On Mars?, Changes and I’m going… I said ‘David most albums have got one decent track and you’ve got some blinders here’. I mean every track was a blinder!”

Recalling the first time he heard Life On Mars?, Wakeman told an audience at one of his gigs: “It was one of the most beautiful songs I’d ever heard… He asked me to play it through. ‘Well, how do you want me to play it?’ And he said, ‘Well you know how I want you to play it.’ I said, ‘I don’t, that’s why I’m asking you.’ And he said, ‘just play it!’ So I played it, and he said. ‘That’s how I want you to play it.’”

Bowie himself was to recall that now fabled occasion slightly differently, when discussing it later for BowieNet, saying: “Lovely fella, Rick, however his memory is as loopy as mine in some places. Several songs on Hunky Dory were written on piano, e.g. Life On Mars? and Changes for starters, not guitar. I played my plodding version and Rick wrote the chords down, then played them with his inimitable touch.”

During those early months of ’71, after returning from a short trip to the U.S., Bowie would write almost forty songs at Haddon Hall, many of which, plucked on a battered 12 string or plonked along the keys of his old grand, would later appear on Hunky Dory, and The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders From Mars. The very first, Oh! You Pretty Things, written in early January, would become Peter Noone’s first solo single in the meantime, although you have to wonder if the former Herman’s Hermit truly understood exactly what he was singing about on Top Of The Pops? Even if Noone, at Bowie’s suggestion, did change the line “The earth is a bitch”, to “The earth is a beast”, to ensure that the song received more airplay, the Homo Sapiens had, apparently, still outgrown their use. Oh! You Pretty Things would also prove to be a huge inspiration to writer Roger Price, who would use the song’s premise to help create the hugely successful ITV children’s drama series, The Tomorrow People, a couple of years later.

Peter Noone told the NME: “My view is that David Bowie is the best writer in Britain at the moment…Certainly the best since Lennon and McCartney.” Noone’s version would go on to be a commercial success, peaking at number 12 in the U.K. Singles Chart and giving a very relieved Bowie his first hit since Space Oddity. It would seem, slowly but surely, that David Bowie was beginning to find his way back, and starting to free himself creatively.

“Two years ago,” Bowie would tell an interviewer later that year, “I used to be the most serious of serious people. I used to come out with great drooling epics which were really tedious and boring, and since I’ve got back from the states my material has become a lot lighter. Before I went over there I used to think I had problems. I decided it wasn’t worth singing about myself, so instead I just decided to write about anything that came to mind.”

“The music is the mask the message wears,” he would reveal in another interview, “music is the Pierrot and I,” he continued, “the performer, am the message.”

Bowie, along with his band, Mick Ronson – “my Jeff Beck”, as Bowie would always proudly refer to him – drummer Mick “Woody” Woodmansey and brand new addition Trevor Bolder, who replaced Tony Visconti on bass at the very last moment, entered Trident Studios in London, on the 8th June 1971, to start recording the songs that would appear on Hunky Dory, starting with Song For Bob Dylan. Co-producer Ken Scott, who Bowie would refer to as, “my George Martin”, recalls: “One of David’s greatest skills is assembling teams, and on Hunky Dory he set up his first real team… When he put a team together he trusted everyone implicitly.” This “team” in particular, three young lads from the northern town of Hull, would, just months later, go down in rock folklore, becoming much better known as, The Spiders From Mars.

Bowie believed in doing as few takes as possible when recording, preferring instead to capture the “freshness” of any performance, the “nervousness” that he always believed contributed strongly to his songs and that made them, “accessible”.

“We didn’t really rehearse any of the songs,” new arrival Trevor Bolder remembers of the Hunky Dory sessions, and of his time with Bowie. “We just ran through each song a couple of times at Haddon Hall, just to get the gist of them, and then went straight into the studio.”

“Or you’d get in on Monday,” Woody Woodmansey tells MOJO, “and he’s finished another and nobody’d heard it. He’d play it to us in the studio and we’d be going, ‘Fucking hell, is there a middle eight? How many choruses does that repeat? How does it end?’ He’d go, “Ken, is it rolling?’ And we’d be like, ‘Oh fuck!’ You were on a knife edge. Sometimes you didn’t know what you’d done really until you went up to have a listen.”

“I was just terrified of screwing my part up and ruining the whole thing,” Bolder admitted. “It was terrifying when the red light when on!”

“A really nice guy,” is how Ken Scott recounts his first impression of a “rather quiet but very sweet”, David Bowie, though he has since admitted that he could never see the singer as ever, “being big”. So, when Bowie asked him to co-produce the album?

“I jumped at the chance. I wanted to move on from engineering,” Ken had just finished work on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass. “I thought I’ll have the luxury of making mistakes ‘cos no one’s ever going to hear this album… And then, three weeks later, I heard the tracks and the light bulb went on,” he is quoted as saying on Marc Riley’s podcast, The A to Z of David Bowie. “It was, Oh shit! He’s going to be huge.” Changes, Life on Mars?, Quicksand, The Bewlay Brothers. “They are all brilliant, brilliant songs!”

Changes, which opens the album and immediately sets its pace thanks to Ronson’s arrangement, had been debuted by Bowie during a very early morning appearance at that year’s Glastonbury.

The song gives a looping melodic voice to all his frustrations, an outlet to his increasing fear of failing to become a star, that his time had come and gone.

“Changes was basically him saying, ‘Y’know, I’ve kind of fucked up ’til now,’” Woodmansey told MOJO. “‘But watch out.’”

“When he starts Changes,” former manager Tony Defries revealed during a very rare interview for the magazine, and looking back for the album’s 50th anniversary, “he says, ‘I still don’t know what I was waiting for. And my time was running wild. A million dead-end streets.’ It’s like he hasn’t got time to reach that place that he’s striving to reach where people recognise him.”

Best friend, and former King Bees bandmate, George Underwood disagrees. “He was just restless, and like a volcano about to erupt.”

“Time may change me,” Bowie prophesies at the end of the opening track, “But I can’t change time.” Although he never stopped trying.

One song in particular has become synonymous with Hunky Dory, and with David Bowie. A song reckoned by many to be his very best, even today regularly vying for the top position in many “Greatest Songs” lists, but Life On Mars?, penned in a Beckenham park one sunny afternoon, is another track born of frustration and scribbled down quickly whilst in the midst of a grudge.

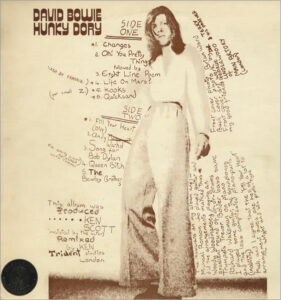

“Inspired By Frankie”, Bowie wrote beside the handwritten credits on the back of Hunky Dory’s sleeve, still simmering that his lyrics had been unceremoniously rejected for the English version of Jacques Revaux’s song, Comme D’Habitude. Bowie’s version, titled Even A Fool Learns To Love, was discarded out of hand, and was to remain largely ignored after Paul Anka acquired the rights to Revaux’s tune, re-wrote it as My Way and promptly handed it to Frank Sinatra.

“Fucking hell, it sounded outstanding,” Woody says of Life On Mars? today. “With Rick playing, it made everybody put an extra bit [of effort] in as well. I played it really heavy,” he admits in MOJO.

Rick Wakeman hadn’t been Bowie’s first choice though. As a fan of Not Only… But Also and Derek and Clive, and well aware that the comedian was also a classically trained pianist, Bowie had originally wanted Dudley Moore to interpret his creation and bring it to life, but he was never to receive a reply to his letter of introduction and enquiry.

“I didn’t receive it,” Dudley told Michael Parkinson many years later. “It would have been interesting though,” he admitted. “I absolutely loved that album, and that song in particular.” Maybe it was for the best though? the star was to add.

Again, Bowie turned to Mick Ronson to arrange and orchestrate the track, something that terrified the guitarist, although he did try to play it cool, repeatedly rolling cigarettes as the BBC string players patiently awaited his directions before the conductor’s baton. After the first take the classical musicians were so impressed with Ronson’s work that they asked if they could do it again, if they could, “please”, try a second take? Just to make sure?

“Mick said, ‘Yeah, all right then,’” laughs Woodmansey. “Bowie and I were going, ‘Don’t roll another ciggie, Mick, for fuck’s sake.’ Then they did it again,” Woody reveals, “and it was even fucking better.”

As they played their final parts though, the bass drum’s heavy last beat and Rick Wakeman’s dangling final chords gradually fading away, a previous take, ruined by a studio telephone ringing at precisely the wrong time, cut in by mistake on the master tape, adding an air of mystery to a song already full of otherworldly mystique and exotic ambience.

Hunky Dory then changes tact and direction again, flowing onwards from the majestic and overtly sci-fi visions that poured forth just before, to now sweep over a listening audience suddenly allowed to settle back and absorb a track that was labelled, dismissively at the time as, “twee”. MOJO says of Kooks that it, “should by rights be a trifle. It’s so daft and jaunty… yet the tenderness and self-doubt resonate with any new parent who wonders if they’re up to the job.” Now, 50 years later, the track is recognised as one of the most genuine, warm and tender love songs ever consigned to record. Influenced by early Neil Young recordings, Kooks was dedicated, “for small z”, Bowie’s newborn son, Duncan Zowie Hayward Jones – and no, he was never christened Zowie Bowie! Kooks made its debut during John Peel’s BBC radio show, In Concert, on the 3rd June and was broadcast for the first time just over two weeks later, in a recording that was finally to be released on the Bowie at the Beeb album.

“Will you stay in our Lovers’ Story/If you stay you won’t be sorry/‘Cause we believe in you”.

Recorded on the 14th July and influenced by the occultist Aleister Crowley, Nietzsche’s concept of the Supermen, Nazism and Bowie’s interest in Buddhism, Quicksand is thought of by many Bowie fans as one of his most underrated tracks. Again it features string arrangements by Ronson as well as David’s acoustic 12 string guitar overdubbed again and again, an idea Ken Scott came up with as he tried to recreate the same sort of powerful sound he had engineered on All Things Must Pass.

“The chain reaction of moving around throughout the bliss and then the calamity of America produced this epic of confusion,” Bowie said of the song. “Anyway,” he added, “with my esoteric problems I could have written it in Plainview or Dulwich.”

Rolling Stone magazine immediately picked up on Bowie’s “superb singing”, and the, “beautiful guitar”, from Mick Ronson, while N.M.E. described it as, “Bowie in his darkest… most metaphysical mood”.

Three songs included on the album would pay what Bowie hoped would be seen as homage to those who had influenced him from afar; Song For Bob Dylan – “Hey there Robert Zimmerman/I wrote a song for you/About a strange young man called Dylan/With a voice like sand and glue” – was his ode to Dylan’s very own, Song To Woody; the supremely pop-artish and whimsical, Andy Warhol; and the hard rocking Queen Bitch: “White Light returned with thanks”, Bowie would again scribble across the back of Hunky Dory’s back sleeve as a nod to the Velvet Underground and Lou Reed, whose solo album Transformer he and Ronson would later produce and arrange.

Like Kooks, Queen Bitch had been debuted during In Concert, before being recorded for Hunky Dory sometime between the 20th June and the 26th July. Inspired by the Underground’s White Light/White Heat, Queen Bitch is driven by Ronson’s guitar pantingly breathing life into a hypnotic but rocking riff, the perfect accompaniment for Bowie’s provocative and aggressive lyrics that incite colourful and seedy imagery of New York drag queens and a bitter, rejected gay lover: Wakeman’s piano and Bowie’s softer acoustic guitar replaced for just a few, “in your face”, minutes… Enough time to give the listener the briefest of excitable hints of what was to come and on the new direction Bowie and The Spiders were about to embark. The track is still widely regarded today as one of the best glam rock songs of all time. Andy Warhol however, reportedly hated his ode, choosing to walk out of the room as it was played to him, only returning later to comment on a now embarrassed David Bowie’s somewhat colourful shoes.

“He’ll think about paint and he’ll think about glue/What a jolly boring thing to do”.

Hunky Dory concludes with the most confused, and probably the most confusing song, that David Bowie has ever written. The Bewlay Brothers was recorded at the last minute, and, according to Ken Scott, after the rest of the band had gone home for the night. As Scott told David Buckley for his excellent 1999 book, Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story, the track was originally written especially for the American market, because, “the Americans always like to read things into things“, even though the lyrics, “make absolutely no sense”. Others immediately pointed to what they saw, or heard, as clear references to Terry Burns, David’s half brother, who suffered from schizophrenia, a condition that haunted and terrified the singer. Bowie would later suggest in a 1977 interview, that maybe the song had been a subliminal message, and that it had been, at that time, “very much based on myself and my brother”. In 2000 he elaborated further to author Nicholas Pegg, for his The Complete David Bowie, saying that the song was, “another vaguely anecdotal piece about my feelings about myself and my brother, or my other doppelganger. I was never quite sure what real position Terry had in my life,” he would add, “whether Terry was a real person or whether I was actually referencing another part of me, and I think ‘Bewlay Brothers’ was really about that.”

John Mendelsohn of Rolling Stone magazine would write, “‘The Bewlay Brothers’ sounds like something that got left off The Man Who Sold The World because it wasn’t loud enough. Musically it’s quiet and barren and sinister, lyrically virtually impenetrable…and it closes with several repetitions of a chilling chorus sung in a broad Cockney accent, which, if it’s any help, David usually invokes when he’s attempting to communicate something about the impossibility of ever completely transcending the mundane circumstances of one’s birth.” See, even the reviews were somewhat confusing!

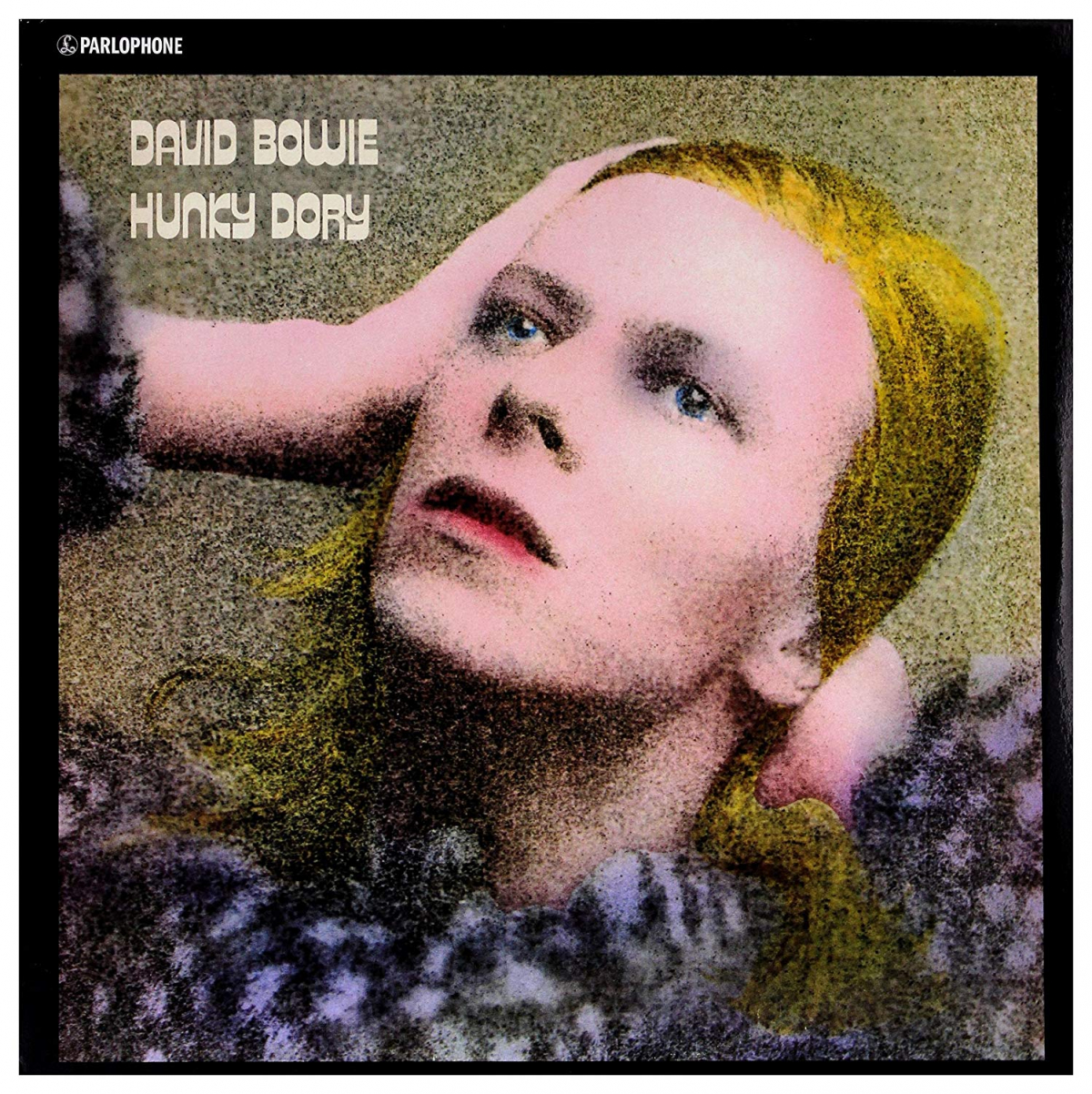

And yet, despite the critical acclaim both the album and the songwriter received upon its release and during the months that followed, David Bowie, and Hunky Dory, with its George Underwood designed, Garboesque sleeve, remained largely ignored.

Melody Maker said of his new album, that it was, “the most inventive piece of song-writing to have appeared on record in a considerable time”.

Danny Holloway of the NME went even further, gushing that it was Bowie, “at his brilliant best,” and adding that “[Hunky Dory is] a breath of fresh air compared to the usual mainstream rock LP of [1972]. It’s very possible,” he claimed, “that this will be the most important album from an emerging artist in 1972, because he’s not following trends – he’s setting them”. Holloway probably never realised just how prophetic those words would turn out to be.

By the time of Hunky Dory’s release, David Bowie had already moved on, such was his creative urge and drive at that time. He, Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Mick “Woody” Woodmansey, were already back in the studio with Ken Scott, putting down brand new songs and coming up with a whole new look that was destined to change the world. Everything was about to change; out of the sepia of post war monotony, to full bright and dazzling colour, brought to you from a being seemingly not of this world. Bored teenagers were about to witness a creation that would change their lives and influence their thoughts and their music forever. In a few short months, a star with bright red hair – was it a boy or a girl? – would stare down the camera’s lens, into your living room and speak directly to you sitting crosslegged on the living room floor.

“I had to phone someone so I picked on you/Hey, that’s far out so you heard him too!/Switch on the TV we may pick him up on channel two”.

That however, is another story.