The universe reclining in your hair!

“I think Electric Warrior, for me, is the first album which is a statement of 1971 for us in England… If anyone ever wanted to know why we were big in the other part of the world, that album says it, for me.”

I began to write this article on the anniversary of Marc Bolan’s death. I began to compile it flicking through grainy black and white images of a wrecked mini. I penned the last paragraph whilst looking at still images of 70’s rock royalty, parading into the church, one after the other, attending his funeral just four days later; David Bowie, Elton John, Rod Stewart, ready to say their goodbyes and obviously still very much in shock, walking with their heads down into the crematorium, between all the wreaths lining their way serenely, including a towering white swan: sad reminders from the pages of newspapers and music magazines of the time, that can now be dredged up from the bowels of the internet by the press of a key or at the point of a computer’s mouse. Looking and reading and searching, as I listen to the album that just 6 years before had brought T. Rex to the forefront of a very bored youth’s suddenly reinvigorated imagination.

Just six years!

Such a lot had happened in those six years. The face of music had changed. Glam Rock had come and gone, exploding onto a weary and wary consciousness before its flame had eventually dimmed beneath the spotlight, now some sad and macabre caricature floundering on the shore, thanks to pale impersonators jumping on rapidly hitched bandwagon; Sweet, Slade, The Bay City Rollers and Gary Glitter to name just a few.

The U.K. though, had evolved from its suburban surroundings wallpapered in clotted browns and draped with uninspiring greens, and had seen something beyond the still-fresh scars and littering debris of the war years. It had emerged out of the shadows, into a world that was sparkling and rich with suddenly dazzling attractions and wondrously vibrant sounds: a newborn hope. Suddenly, this new world, the whole universe even, was now tantalisingly within reach, and all of it glistened and glittered: from boring tank tops and dull corduroys to cat suits of dazzling silvers and beguiling golds. Young bands with something new to preach, free from denim and leaving behind folksy reminiscences, now tottering across the stage on large platform shoes and with space symbols crafted upon their foreheads or pencilled around wide eyes sparkling, singing songs that enraptured weirdly new and rapidly burgeoning ideas coloured in the most imaginative science fiction. From behind the cleverly applied mascara and the layers of wet-looking lip gloss, this new sound and gregarious look reached out through the television screens and from upon the stage of what had once been a safe Top of the Pops.

“Get it on, bang the gong. Get it on!”

Mark Feld, now the other-worldly Marc Bolan, “jumped up on the stage”. Such a pretty, pretty boy, soon to be plucked from amongst the hippies and the folksters, to become the 70’s first real idol of young girls and disenfranchised teenagers all over the land, changing the world beneath his feet with lyrics delivered with a warbly whisper and enveloped by cleverly crafted guitar licks.

“He was alright, and the band was altogether”, Ziggy would later sing of Bolan, and from centre stage, he spoke to those who were searching. He soon adorned bedroom walls, replacing posters of a leather-clad Elvis, or The Beatles. As 1971 began to wind down, as fathers mowed little square lawns or lovingly washed their family saloon cars of a Sunday afternoon, Glam Rock duly arrived, crackling from little turntables and blaring free out of bedroom windows.

Electric Warrior was certainly the first noticeable, discernible mark in the sand of “Popular Culture”, the first zigzagging crack that had tentatively begun to appear across the shell of an egg painstakingly laid by then, staid remnants of tired folk-rock with nothing new left to say, the rehashed warnings of impending doom and gloom now falling on ears that had heard it all before, a million times. Of a rock ‘n’ roll movement that was tired and blasé, the same chords plonked or strummed over and over into an almost grateful submission.

“His targets are your common rock & roll cliches, as well as your common pseudo-poetic, pseudo-philosophical rock & roll cliches,” Ben Gerson informed readers of Rolling Stone. “What Marc seems to be saying on Electric Warrior is that rock is ultimately as quaint as wizards and unicorns, and finally, as defunct.”

Electric Warrior was the realisation of something different, something brash and bold. A growing entity that a new generation, weary of suits, bowler hats and eternal deference, could latch on to and call its very own, all painstakingly lavished with glitter. And it was what it would lead to, just a few months later, an androgynous figure lounging about in a catsuit and with bright red hair, that changed everything; together, Bolan and Bowie igniting a world, that would eventually realise Punk and New Romanticism, Alternative and Grunge.

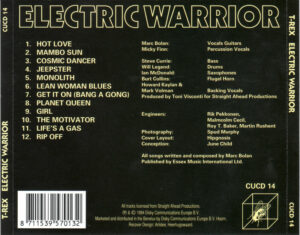

Released a week before Bolan’s 24th birthday, Electric Warrior would take top spot on the UK Album Chart on the 9th October and stay there for 8 weeks, eventually going on to become the best selling album of the year. It was an album that rippled with sexual imagery and that, according to guitar.com, “hosted one of the most electrifying rock’n’roll riffs of all time.” Often copied but arguably never bettered.

“Despite the unrefined 50s rock’n’roll fundamentals of Bolan’s riffing and the occasionally nonsensical mysticism of his lyrics, here was a revolutionary record that altered the course of rock history, unleashing a glam wave that would be surfed by David Bowie, Slade, Mott The Hoople et al deep into the 70s.”

“My new album is called Electric Warrior,” a dazzling Bolan proudly announced to the world through that month’s Record Collector, “and it crystallises what I’m doing now. This is our album,” he continued, insisting confidently that it would go on to become, “the one that people will remember”.

“Electric Warrior stands the test of time as the glam rock album of all time,” Soundblab insists, “because it was the first to condense the movement into 40 minutes of all killer – no filler.” It predated Ziggy Stardust and carried Bolan to the top of the charts long before Bowie, at that time still relatively ignored and engrossed in crafting and recording the songs that would eventually make up Hunky Dory – but much more of that later! A newly reinvigorated Bolan then, adorning television screens and confidently soundtracking radio shows, but secretly carrying concerns and regards for his old audience.

Would they follow his new direction?

Would they understand why he wasn’t still sitting crosslegged on a matted floor with his old acoustic guitar strung across his lap?

Influential radio DJ John Peel, until then the band’s biggest supporter, was bitingly angry at the sudden change of course, not shy in his damnation at Bolan and T. Rex for “changing horses”, as he bitterly saw it, before barking dismissively against Bolan’s show of “shallowness”. Others though clearly saw genius in the making.

“Just listen to that chariot choogling throughout opener Mambo Sun and swoon as Bolan and Co. synthesize Creedence Clearwater Revival’s swamp gas chortle into a funky f-beat a full five years before Costello, Lowe and their Stiff compadres,” Jeff Penczak wrote for the webzine Soundblab, quickly adding that his “perfectly-timed solos illustrate Bolan’s oft-overlooked guitar skills, while his prime-evil [sic] guttural utterances scream ‘Me, Tarzan, You Jane’.”

“Marc is criminally underrated as a guitarist,” the album’s producer Tony Visconti said later during an interview for Guitar World. “All rock ’n’ rollers love T. Rex, and there’s a little bit of T. Rex in every rock ’n’ roll band… If you saw him play live, he could really improvise; he had no problem playing a 20-minute solo,” Visconti laughed.

“Jeepster and Get It On,” the album’s two singles are, Penczak insists, “blatant sex prowls… Bolan hunting and grunting his way into anything in skirts…”

Get It On was the band’s biggest selling single, and would become T.Rex’s only U.S. top ten hit, but then, Electric Warrior was an impatient Bolan’s deliberate attempt at finally winning over a U.S. audience that had, until then at least, largely ignored him. According to those who knew him at the time, if he was ever to conquer the States then he had to do it immediately. Those around him noticed that he seemed to have a driving sense of urgency. As drummer Mickey Finn is reported to have said later, it was as if he knew that time was not on his side, that he had “precious little time available in which to accomplish everything he wanted to?”

The demos for the album were recorded in the utmost secrecy at Bolan’s home, the singer afraid that somebody would steal his ideas.

“Marc was terrified of being ripped off; he would have never handed demos out to anybody,” Visconti recalled during an interview with Guitar World, reflecting on the pop star’s genius. “Everything you hear on a T. Rex record was a live recording; nothing was replaced later on… I loved that the sessions were very live,” he added. “I also loved the fact that he dressed to record. He wore his stage gear and his platform shoes. He’d be jumping up and down like he was on stage; everything was really great fun. We also invited friends to the sessions, so he liked to see maybe five or six people bouncing about in the control room. He always loved an audience.“

“He would teach us the songs chord by chord, telling us the key changes as we went along,” Finn remembered. “That was how we learned, playing and recording everything live… I remember ‘Get It On’ being taught to us later on,” in the sessions. “We all knew that it would be a hit,” he insisted. “There was just a real excitement, a buzz.”

The earliest recordings are reported to date back to the March of ’71, although, to Visconti’s recollection, the recording only began after the band had finished their US tour in April, and would be completed that June, ready to be fully mixed by the end of July, by which time ‘Get It On’ had been released to favourable acclaim, giving T. Rex their second number-one single in the UK and, as Bang A Gong (Get It On), their biggest hit in the US. John Peel though, refused to play it, accusing the song of lacking, “something of the T. Rex I know and love”. Bolan would feel betrayed by his friend, and quickly distanced himself from the radio D.J., although he would continue to acknowledge the help and support Peel had given to him and his music.

“I don’t see him as often as I’d like to, but I’ll always be grateful for the way he tried to make people take notice of us,” the singer is reported to have said later by Record Collector.

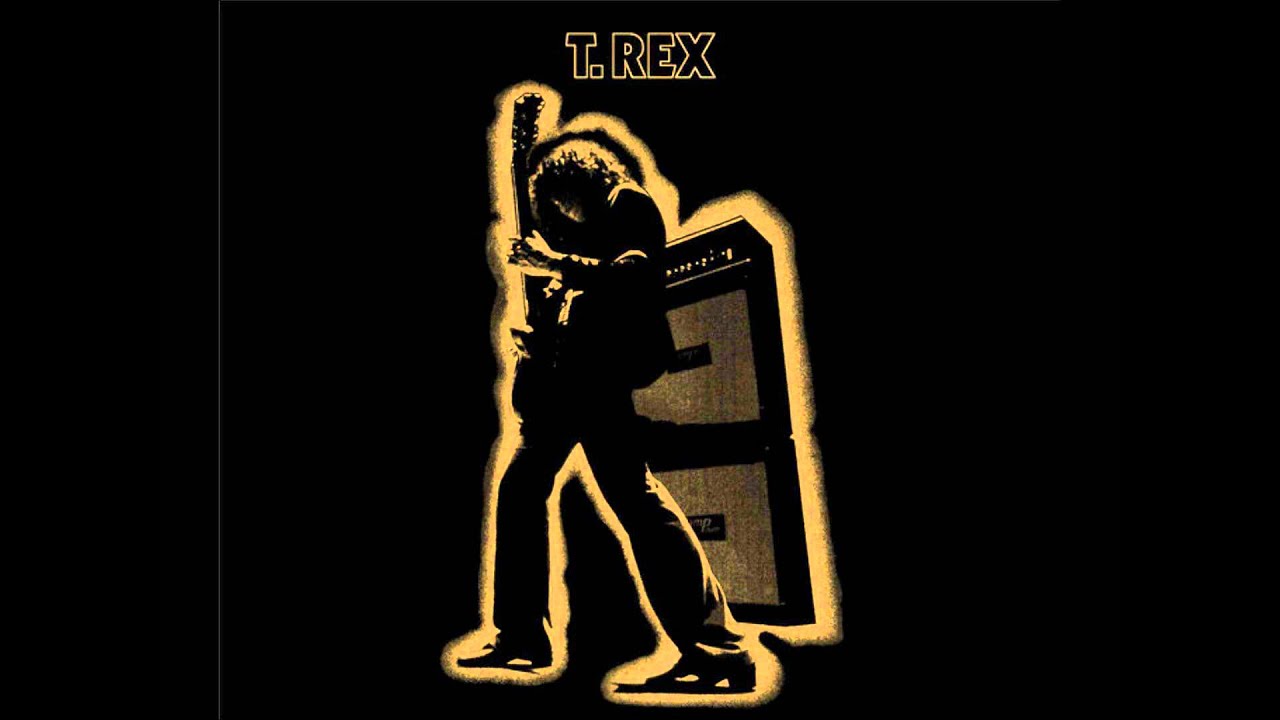

The image was all-important too. The album’s cover, based on a photo taken by Kieron Murphy, of Bolan standing dark and open-legged whilst thrashing an electric guitar, is almost superhero-like, with the amp and loud speaker behind him supposedly adorned, like some protective cloak.

“Marc Bolan became a star and T. Rex became a supergroup,” Chris Welch had written in Melody Maker.

“I’ve got this sound in my head that is definitely unlike anything else we have put out,” Bolan told Nick Logan for the NME “It really is cosmic rock.” And it really was.

With Electric Warrior, Bolan and T. Rex – Steve Currie, Mickey Finn, Bill Legend, and guest musicians including Rick Wakeman, who plays keyboards on Get It On – would write the first chapter of what came to be known as Glam Rock, and they would no doubt influence David Bowie, who nine months later would, according to Melody Maker, go on writing the rest of the book.

And so, I finish writing this article on what would have been Mark Feld’s 71st birthday, aware that for him it had not been a long journey, as he seems to have feared and foretold. It was something meteoric and it changed the face of popular culture and influenced more than just a generation. There had never been such a seismic shift, and arguably, there never has been since.