The first proper gig I ever went to was R.E.M. at Slane Castle in Ireland. It was July 1995 and our hired minibus consisted of 24 R.E.M. nuts; we set off in the wee small hours to make the 100-mile trek and beat the queues. The show was intense, primal, it remains the gig of a lifetime and it was the moment I fell in love with the most amazing I’d ever see. Slane has seen them all, its history is a who’s who; Thin Lizzy, The Stones, U2, Dylan, Queen, Bowie, Springsteen, RHCP, Madonna, Oasis, Eminem, Foo Fighters, and so many more, it has been home live films and TV shows. As a thing, a Slane gig is a seminal moment in any Irish teens life. The R.E.M. show and this is not hyperbolic, was a turning point in many people’s lives, a moment in time that a generation returns to when it looks back over their years in music.

That this gig was part of the Monster tour meant months of worry that it might not happen. Between aneurysms and appendectomies, a punishing tour schedule the band weren’t ready for and last minute licensing blips, the fear of cancellation was palpable. When the band cancelled shows at the start of the summer of ’95 we were broken, convinced Slane would be lost. It was a momentous thing to walk through the gates and downhill toward the stage.

We found ourselves 10 rows from the front, huddled together we stood our ground; we spent the day baying like wild animals, wailing, screaming, bartering for slops from half drank pints and begging strangers for water in a desperate attempt not to surrender our spot. Or faint. We would not be moved. In the space of 10 hours on a balmy July day, we fell in love, had our hearts broken, cemented friendships and made new ones that have lasted a lifetime. One case in point involved our friend Danny, who was swept off his feet by the newly found Roisin, she was swept off her feet by the sway of the crowd at around 7.30pm and never seen again. I met a girl just before teatime and we’ve been friends from that day to this. Danny, well, Danny was distraught.

With support from Luka Bloom, Spearhead, Belly, Sharon Shannon and Oasis the day went by in a blur. The moment we spotted a rigger strapping himself into a spotlight strung from the stage roof we collectively held our breath, 95,000 people just stopped dead. The Stipe was near. The moment was upon us.

This was one of the most hyped Slane shows in years and it was about to go off, for 23 beautiful songs we sang, we swore, we wept, we hugged, we kissed and we applauded the human pyramids. We were surrounded by love and joy and at one point actual fire. 95,000 people set fire to paper cups and held them aloft during ‘Everybody Hurts’, it was the most beautiful thing we’d ever witnessed, and a scene that has never been repeated.

Growing up in rural Ireland in the early ’90s meant one thing. The fashion, culture and music were invariably shit. There was nowhere for decent coffee, there really was no such a thing as decent coffee. There were bars, but on the basis that we were warned not to walk past many of them, the idea of drinking in one was a daunting prospect, one that would end with you face down in a drain, safe spaces these were not. The remaining establishments, well, I could walk into any number of them now, years later, blindfolded and still tell you who is sitting where. They are those kinds of joints. Lots of booze, lots of laughs, lots of camaraderies, but they need a lick of paint and a younger clientele.

There were three options for the consumption of music. The first was ‘Clublands’ trance cassettes from nearby Cookstown, a rural town that had nightclubs by dint of the fact that it was in the middle of other small places and had a market. People congregated there and consumed vast quantities of MDMA, dancing to shit trance music in tacky clubs that were little more than barns.

The second option was country music cassettes from Ballymena, another rural town overflowing with evangelical protestants who made the news because they banned OMD from playing on a Sunday. Those God-fearing ladies and gentlemen never heard of Scooter, whatever that was. Their music was produced by Philomena Begley or Uncle Hugo and no, you don’t need to Google them. It’s the worst kind of country on earth. The third and final option was bad rock music frequently piped loudly through the sound system of cheap cars with their windows down on their 47th lap of one of those market towns…

Brothers and Sisters, we are gathered here today to hear the communal confession of one Christopher Flack, of Co Antrim and I apologise in advance. As a teenager, I spent some time listening to Bon Jovi. The nearest thing we got to something exotic was Van Halen or David Lee Roth and those were only on days when Glen had the car, a brown Ford Cortina that had seen better days. I don’t wish to besmirch the good name of David Lee Roth, nor question his work ethic, but it didn’t do much for this writer. It was the mid-’90s and music everywhere was about to change. Even in Antrim.

I was blessed to befriend the Melly clan. Seamus, Roisin, Clare and Anne; I was one of their own and they taught me many things, primarily about human communication and picking up wildly obvious hints that I was continually missing. They also taught me about music. What I learned quickly was that while I met Seamus in school, Anne and Roisin, the elders of the clan, had spectacular taste in music. It was through the Melly clan that I discovered R.E.M. and Monster. It was the Melly Clan that arranged the bus to Slane Castle, to R.E.M., the same clan that made the magic of seeing R.E.M. with 95,000 screaming, jumping, singing lunatics in a field in County Meath a reality.

The Melly Clan were my gateway drug, and what a trip it has been.

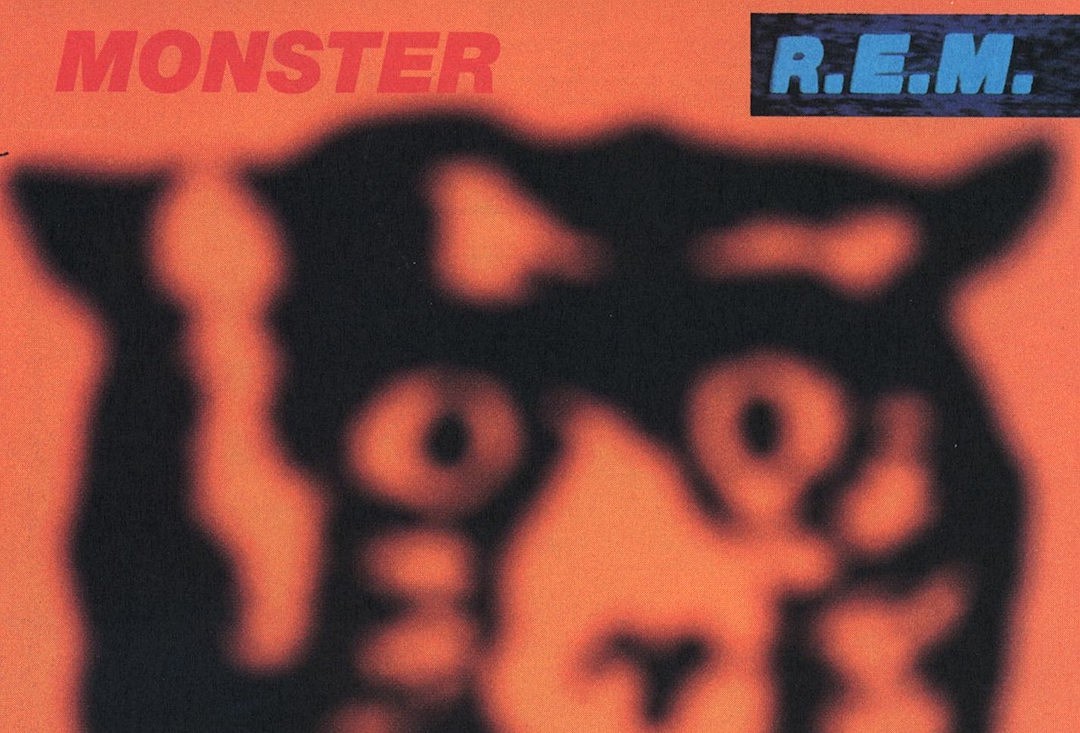

My ears were open to things I’d never heard in a Ford Cortina – Radiohead, Pulp, Beck, Eels, The Charlatans, Primal Scream – and it made me look to Manchester, it made me look to Sheffield, it made me look anywhere that wasn’t the ‘Bailiwick Lounge’ or Antrim. The record that floored me was Monster. I’d listened to some R.E.M. stuff with the Melly clan previously, but nothing dragged me in quite like Monster. I have memories of Green, Out of Time and Automatic for the People, but the first few chords of ‘What’s The Frequency, Kenneth?’ well, they blew the bloody doors off.

If I haven’t heard it for a while, those opening chords do the same thing now as they did then. There’s a rush of adrenalin, a quickening of the heart, the spine-tingling, hair on the back of the neck standing joy of something that has given you so many memories, given you so much joy yet it still sounds young. ‘What’s The Frequency, Kenneth?’ was the first song they played when they stepped onto the stage at Slane, no one was convinced they were going to appear on stage until they did. Those first few chords. I don’t think I’ll ever forget the sheer pandemonium. The elation.

The oblivion.

Bill Berry wanted noise and Bill Berry got what he wanted. REM delivered Monster having never done gritty; they’d never done sex, they’d done ballads and a little college scuzz, but this was something else. It was a statement of intent, they were still R.E.M. but the Emperor had thrown out the wardrobe department and gone down to the fancy dress store, dug out an Elvis costume and was ready to rock and roll. Every track on Monster is a step further away from mandolins, a step further away from the R.E.M. we knew, this was deeper, darker, dirtier. This was an album that was dragged kicking and screaming through three studios, emergency rooms, tooth abscesses, and the tragic deaths of River Pheonix and Kurt Cobain. ‘What’s The Frequency, Kenneth?’ is about a vicious beating CBS’ Dan Rather suffered in New York City, in the video we see a bald Michael Stipe for the first time. He had shorn the locks and the look of the two previous records, this was new territory in talking about the passion.

In a world that had Green Day and Oasis, Monster sat in a green room of its own, bringing the audience of earlier records along for the ride in a guitar-laden truck through the heart of middle America. Monster is a record that smashes at the idea of the artist as a commodity, something you can contract. In ‘Crush with Eyeliner’, Stipe lashes out about reinvention, at creating an identity for the camera, for MTV. And Thurston Moore chimes in to sing “I’m the real thing” in an effort to prove the point.

‘King of Comedy‘ is the most polished, the most commercially ready, though I’ve always felt that was done on purpose, it’s almost as though Stipe & Co are taking the piss. It opens with the lines “Make your money with a suit and tie/Make your money with shrewd denial/Make your money expert advice if you can wing it,” and ends with the refrain “I’m not a Commodity” repeated into the ether.

The sex references come in on ‘I Don’t Sleep, I Dream’, yet it’s not sexy per se, it’s a little creepy, a little gross perhaps, it might be another suggestion that people look at you differently when you travel with a crew and a record contract. As a line, “Are you coming to ease my headache?/Do you give good head?/Am I good in bed?” hardly needs any further description from me.

‘Star 69′ is about an obsession with a phone stalker, the last call return, the constant need for attention, it’s seedy for all the wrong reasons, gritty, grimy. It’s almost unpleasant but gloriously noisy. ‘Strange Currencies’ is a song about lost love, broken hearts, maybe, somewhere, it’s a song about what happens when you finally talk to that stalker on the end of the phone. If the rumour is to be believed ‘Bang & Blame‘ could be about River Pheonix, it could also be about any number of relationships Stipe had, the anger in “The whole world hinges on your swings/Your secret life of indiscreet discretions” is a call for openness, it’s needy, longing, maybe it is about loss. The one thing we can be assured of with the vast majority of Stipe’s lyrics is that we will never really know what he’s talking about.

For me though, one of the highlights is perhaps the quietest track of the 12, ‘Let Me In’ is a song, rather cheerily, about death, about the death of Kurt Cobain, about loss, suffering, and heartbreak. The third verse is a lesson in singing about suicide, about loss, the lines flow in such simplicity yet they give a real in-depth look at the impact of Cobain‘s loss on Stipe, on the band, on a world of music that was in flux.

“I had a mind to try to stop you

Let me in, let me in

And I’ve got tar on my feet and I can’t see

All the birds look down and laugh at me

Clumsy, crawling out of my skin.”

On ‘Let Me In’, Mills’ guitar is almost lost, gentle, misty, on the shoegaze side, if Berry is in there it’s lost on my ear, and has been since my first listen; on ‘Let Me In’ it’s the Buck organ that brings you along with the lyric, it’s the organ that gives the track its soul and its sadness. It is beautiful. The whole album is beautiful.

Monster gave me the reason to dig through every box in every record store, it gave me the impetus to queue through the night for gig tickets, to drive stupid distances for shows and to ingest every note I can get my hands on. It’s a stunning thing.