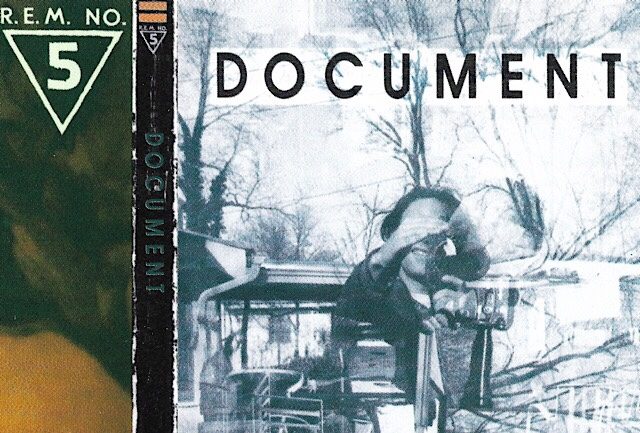

Nashville. 1987. R.E.M. are recording Document their final album for their independent home I.R.S., their first album with Scott Litt (Carly Simon, Ian Hunter, the dbs), the producer they met recording ‘Romance‘ for a film soundtrack. For the next six records, their working relationship would become intrinsic to their artistic blooming and commercial success as a band.

Document lit the fuse and it sounds humongous: a sound crafted for stadiums, the switch has been flicked and R.E.M. finally sounds like a band who could comfortably fill stadiums and football grounds. Document is possessed of a muscular live sound, its clarity and directness is constructed and lays the foundations for the live arena domination of future years, but it also sounds industrial armour-plated, and self-confident like a tank trundling into the battlefield. Intersecting the post-punk of Wire and Gang of Four and the work of the Byrds, Television and new wave, it was the distillation of everything R.E.M. had been working towards for the last much of a decade.

Whilst U2 wrote music for stadiums, from the off R.E.M. had time to develop, play hundreds of shows, and experiment in the studio. To grow into the role of arena band, they did things on their terms, they didn’t appear on album covers, didn’t have lyrics in their album sleeves (up until this point), they were a democracy split four ways, and they wanted to make artistic statements. Thus when they got there they still retained what it was that made R.E.M. special their ability to shift, to infuse an artfulness into everything they did and speak to everyday people in a way many cliched MOR rock bands didn’t, not to play the “game”, because they were still four humble softly spoken art students from Athens.

“We wanted to make a tougher-edged, loose, weird, semi-live, in-the-studio album,” Peter Buck told Rolling Stone just before Document was released. “I don’t see this as the record that’s going to blast apart the chart, although you never know. Weirder things have happened.”

The band said they wanted Document to be a record of their early years and to the “crazy crazy times” they were living in. A document of an era, a time. A struggle to be heard feeling that change can only happen when we point out injustice and band together to oppose. But it’s also a launching pad, as they move towards bigger audiences and a major label. Document was intrinsic to this shift, and formidable in its own right if slightly frayed at the end.

Scott Litt found the balance between folk and rock and the balance between the individual band members songs on a tracklist. Building on the work Don Gehman did with Lifes Rich Pageant, his production added a new clarity and a bold, expansive, timelessness to their ever-changing songs. A sound they had honed and built towards over hundreds of gigs across the world and four albums in as many years since their debut 1983’s Murmur.

Unlike portions of the more eclectic tracklists of its predecessor’s Fables of the Reconstruction and Lifes Rich Pageant, Document sounds coherently threaded throughout, shorn of much of their trademark melody or jangle, but still wielding it as an exclamation, this is a sound built to last.

Vocally, Michael Stipe sounds as strident and as knowing as he ever had, and well angry – no longer (that) abstract, no longer trying on styles for size, but full-throated and confident, standing firmly in the face of a tumult, steeped in the black humour of it all. It’s a call to action, a call for collectivism, but also a reflection of the fiery furnaces. It broods with paranoia, a menace a disquiet, brutality of the age of the individual, and Wall Street where the working man and the middle class were being screwed. Themes that are just as prescient today. Inequality, misinformation and political disquiet, there was a sense that all wasn’t right with the world in 1987, and Document not only mocks it but bears witness to it.

Peter Buck’s guitars are central to this shift: as prominent as Stipe’s holler, throughout he mangles, crunches and scours, with precision and a menace he hadn’t brought as consistently until now. Less reverb coated melodicism of early jangly R.E.M. and more the spiky off-kilter licks that ring out with brutalism, an angular incendiary quality, that was only hinted at on Fables opener ‘Feeling Gravity’s Pull’. Bill Berry’s huge reverberating drum trembled and Mike Mills’ bass lines laid the firm supports, it’s like post-punk sharpened for liftoff, yet each instrument has space and clarity a space and separation in your speakers, each of the three-way vocals harmonies of Stipe, Mills and Berry honed, like pointy elbows.

Producer Litt turning everything up a notch and yet removed anything superfluous, allowing each instrument its space and clarity, its sound armour plated and indestructible, a widescreen sound built for the live stage. Forged of Reagan’s America, the cold war era of paranoia surrounding the potential for nuclear war. It’s a sound that would come to define the early 90s alternative music, with the likes of Pixies and Nirvana.

If Lifes Rich Pageant‘s excellent ‘Fall on Me’ and ‘Cuyahoga‘ had alluded to the politics of American history, civil war and acid rain, Document is the brashest and nakedly political and sloganeering as R.E.M. had been to this point.

Opener ‘Finest Worksong’ sets the tone: “The time to rise/has been engaged”, asserts Stipe over this urgent and visceral call to arms, sounding like a leader at the pulpit singing of reform and revolution. Fired by stinging repeated one-note, guitars and Berry’s cavernous drums and ever so slightly funky rhythms, Mike Mills adding backing vocals to fantastic effect in the chorus line: the combined effect sounds like a worker hammering away in a sheet metal factory.

‘Welcome to the Occupation’ broods with frustration, sings of the ‘primitive and wild” taking on the warmongers in Latin America. “Listen to me” pleads Stipe in the songs ominous outro an almost desperate plea for democracy. The jittery percussion ‘Exhuming McCarthy‘ pairs unsettled verses with pianos, and brass splashes with Stipe’s queasy almost jaunty tongue in cheek refrains, (“Look who bought the myth, by jingo, buy America“) making parallels between the red-baiting of Joe McCarthy’s time and the sense of American exceptionalism during the Reagan era, prevalent in the Iran-Contra affair.

“Michael is concerned — we all are — about this neo-conservative wave in America,” Mike Mills told the Globe and Mail in 1987. “With all the repression of personal freedoms, the knee-jerk reactionism, it’s the sort of atmosphere old Joe [McCarthy] would fit well into. Hence, the song.”

A college radio hit before it was a single, ‘Its The End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)’ is one of Stipe’s finest list songs, it rattles with choppy riffs, frenetic percussion and the awesome three way singalong chorus, Stipe flicking through a dizzying barrage of information, a blizzard of references to pop culture, 24-hour news and current affairs and the upcoming end of the world, it has elements of Bob Dylan‘s ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ or Patti Smith‘s ‘Horses’ about its loosely assembled stream of consciousness, word jumble. But its gallows humour of the punctuated refrain “And I feel fine”, is delivered with the kind of ironic side-eye that defined the era. Most of all it’s an insidious cold war anthem of rushing dystopia, that took on a new significance in the pandemic. There’s black humour elsewhere too the cover of Wire‘s ‘Strange‘ becomes a slightly unhinged self-referencing song for Stipe, he changes the lyrics to “Michael’s nervous and the time is right”.

Speaking of irony, there’s no little dark irony in the brutal kiss-off song ‘The One I Love‘ which became their biggest hit so far, crashlanding at number nine in billboard charts upon its release. Like Springsteen‘s ‘Born in the USA‘ many ignoring the meaning and the chorus, the references to “a simple prop to occupy my time” and focusing on the dedication to the “One I Love”. But it’s little wonder it’s an undeniably great single, ominous clanging guitars, and looping verses give way to Stipe’s incredible vocal and explosive chorus fired off by Berry’s bounding drums and call returned by Mike Mills’s backing(“She’s comin’ down on her own, now”), like a foreboding storm cloud delivering several thunderstrikes. It’s an incredible single, yet often misunderstood.

So, Document is also an album of violence, and brutal moments, “Fire!” exclaims Stipe on the chorus of ‘The One I Love‘, the “fire on the hemisphere” in ‘Welcome to the Occupation’, the downbeat paranoia of ‘Disturbance at the heron house’, the arsonist’s tendencies and horn shronks of “Fireplace“. “Firehouse” as Stipe sings on the ominous and clanging religious references of ‘Oddfellows Local 151‘. In this company the rhythmic drums and dulcimer laden ‘King of Birds’ positively simmers and doesn’t quite liftoff, but its plaintive interwoven refrains intersect the work of George Harrison and the mysticism of early The Doors. “Standing on the shoulder of giants leaves me cold” he sings with the desolation of helplessness, stretching his voice to breaking point in the last portion.

Document would also hint at what was to come as they pushed themselves musically too, a saxophone was added to ‘Fireplace‘, with Steve Berlin being brought in by Scott Litt to add his sax skills. This experimentation would lead to their adoption of the mandolin, which featured prominently on their subsequent albums Green and Out of Time; the band began swapping instruments both in concert and the studio to explore new sounds.

“It’s a sideways look at the world and us,” Buck said of Document in a 1987 talk with Melody Maker. “It has a kind of Orwellian wry humour. It’s not that we’re making light of America; it’s just that I can’t look at it the way Bruce Springsteen does. To me, America in 1987 is Disney World.” (In fact, it was later revealed that R.E.M. had considered calling this album Last Train to Disneyworld.)

By January of 1988, Document had already gone platinum, becoming R.E.M.’s first million-selling album ever. Whilst their previous four albums to this point showed the roots of R.E.M.’s core, and hinted at the band they could become, their last album for I.R.S, Document marked the end of a chapter and gave them the platform for lift-off.

Topical and immediate Document chisels out a defining statement to where they were, and a testament to the power of their collective, and the start of the sideways view they would take of American life. A clarification of what they were as a live band just at the point where they were growing into the global band they would become, their sound would give way to more experimental and symphonic and accessible pop moments at their artistic and commercial peak. But Document still stands on its own two feet and raises its voice in the world as an album that shaped the late ’80s, not just for R.E.M. and not just for the changing society around them, but for alternative music they had defined. Now they were primed to become universal.