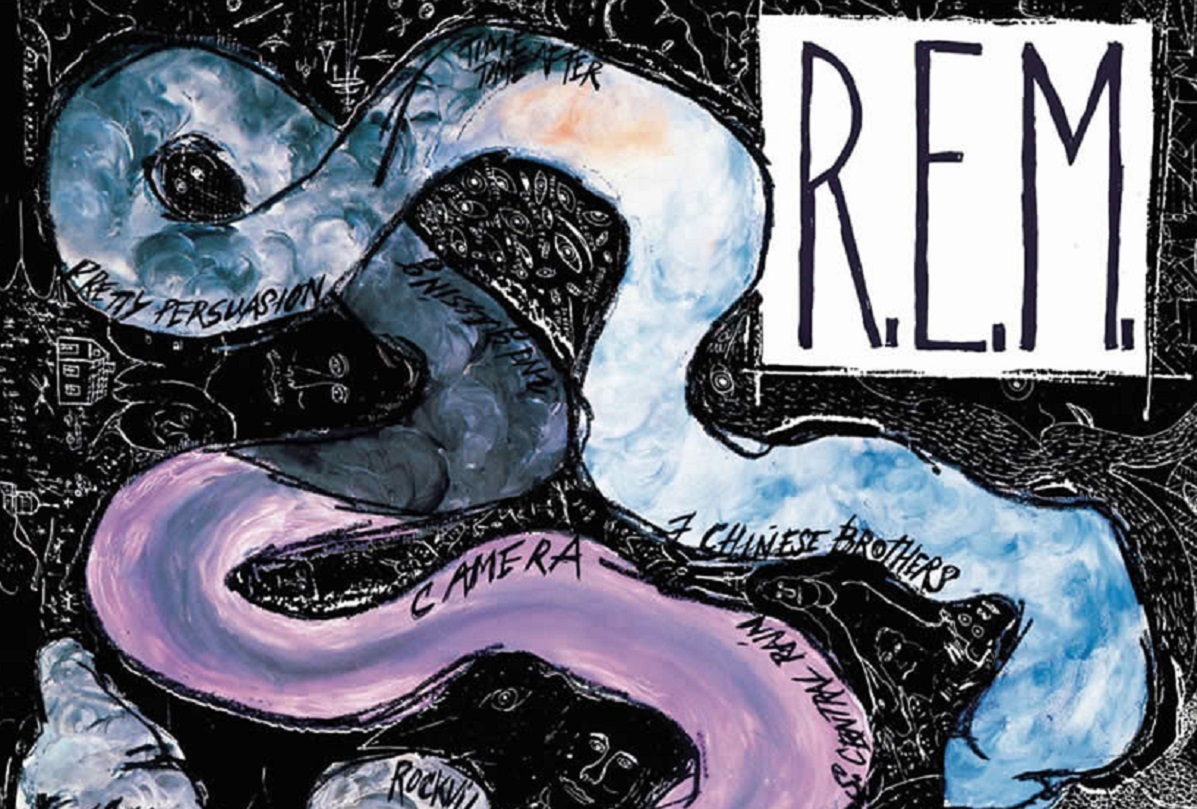

In 1984, just a few days shy of the one-year anniversary of their debut album Murmur, R.E.M. (Bill Berry, Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Michael Stipe) released their follow-up, Reckoning. The band were college radio and critical darlings with Murmur topping endless year-end lists, and the band had been on the road over 100 days between the two albums. Murmur was a dark, earthy Southern gothic album shrouded in mumbled vocals, obscure lyrics and covered in layers of kudzu. Reckoning, by contrast, constantly references water (harbors, oceans, rain, rivers, seas), and evokes how it can appear still on the surface while currents run underneath.

Reckoning is an album about loss (of friends, lovers, relationships, time) and regret, and is very much a product of a band on the road untethered from what used to be home. Being on tour can feel like being stuck in a time loop, where every day is the same but no time has truly passed, and this album reflects on that experience as well as the reality that time really is passing “back home,” or in the physical space you occupy when you’re not on tour. You miss the life around you, friends who were couples break up, they start new jobs, places go out of business, venues burn down, new ones open up, people pass away, the lives of the community keep moving forward regardless if you live there or not, and those shared events are lost to you. Lots of things are gained from relentless touring, recording, writing, rehearsing, but just as many things are lost to it as well.

When I first owned this album it was on cassette, and so I think of it as side A and side B. I’ve tried for years to listen to it as a CD or digitally, but this album feels tracked and sequenced to be enjoyed as two sides, or maybe that is just my preference.

‘Harborcoat’ opens side A and captures that perfect moment where music was moving from the dancefloor stomp of post-punk and to a more optimistic jangle-pop. The music is uplifting, and Peter Buck’s guitar riff would make Johnny Marr jealous, and the drums and bass could be from a lost Pylon song with their simplicity and get-up-and-move directness. The lyrics, on the other hand, are somewhat vague but very dark depending on your interpretation; there has been a debate that ‘Harborcoat’ is a retelling of part of The Diary of Anne Frank, or that it’s about working-class struggle. Within the context of the album, though, it feels more personal, and maybe it’s the struggle to protect oneself coming into a certain level of fame, especially at a young age. The imagery of wearing a big coat and blending to hide, shielding a reddened neck, and hoping the coat can stop or dull the shivs in the back could just be any of the above, but it also lines up with getting noticed outside the small town you are from and with each person wanting you to bring them along there is another that is hoping you fail.

I couldn’t make heads or tails of ‘7 Chinese Brothers’ for the longest time. I remember discovering the children’s tale The Five Chinese Brothers and assumed it had to do with that, considering the selfish and greedy boy who swallows the ocean, but many years later during a deep dive where I was reading R.E.M. interviews, Michael Stipe says the song is about him breaking up a hetero couple, then turning around to date them both. This would be one of the first in a long line of songs following a formula that combines sing-talking verses followed by emotive, raw vocal choruses the band would revisit many times over their career. The slightly affected talking voice narrates the story while you feel the guilt, the pain, or the resolve (depending on how you want to view it). The first chorus has just a touch of emotion, almost hiding the narrator’s involvement, but the second chorus is where we get the pain in the vocal, the backing vocal chorus by Mike Mills, and the tiny “duh duh duh dun duh” Buck guitar flourish, a little extra painful “ooooh, oh” from Stipe, and this slightly heavier drum beat from Bill Berry. You can start to hear the actual remorse. The third and final chorus comes in slightly brighter and more assured. The resolve of “this happened, I played my part, but with time it’s beginning to fade.”

‘So. Central Rain’ is one of the rare entries in the R.E.M. songbook that is as direct and easy to understand lyrically as it is vocally. It has a strong riff and the emotive simple “I’m sorry” chorus is easy to remember and if feeling brave you can try to match it when singing along in the car, but launching an album with a slow to mid-tempo single is a bold move. It’s a simple country-rock song that strolls along giving the listener three verses and three choruses and it doesn’t forget that little bit of magic that set R.E.M. apart from so many college rock bands at the time, that perfect little bit of Mike Mills adding his backing vocal to make the choruses really come alive. Seeing how this follows ‘7 Chinese Brothers’ you might think this is remorse still held over from the track before. A song about a broken relationship strained by lack of communication with time zones between them, either two people live cities apart or maybe one of the people being on tour is always gone from home. Missing these calls and building a story outside what is being said and unsaid is making the distance even bigger than the miles that separate them. If that above isn’t enough ‘So. Central Rain’ makes its real statement roughly after the pop song part is over at the 2 minutes and 30 seconds mark, it’s the non-worded vocal guttural cry and sharp piano ending that drives this remorse all the way home.

Out of the entire R.E.M. catalogue, ‘Pretty Persuasion’ has always been at the top of my list in that this is exactly what they do best, and it is easily one of my all-time favourite tracks of the golden era of ’80s American college rock. ‘Pretty Persuasion’ is almost calling-card early R.E.M. with a guitar riff from beyond, built on descending arpeggios, but the beauty of this track is the speed with which they attack it. R.E.M. get endless comparisons to The Byrds, Velvet Underground, and Big Star, but this one seemed more contemporary, like a hybrid of X and The Soft Boys. I never understood how this wasn’t a single. Maybe they didn’t want to upset the FCC or make a toothless radio edit. The song was released as a promotional single, but not as an official single with B-sides. This is one of the few tracks that was around pre-Murmur, which is why it doesn’t allude to water or sound exactly like the rest of the album. One could think the song might be an allusion to the same couple from ‘7 Chinese Brothers’ and ‘So. Central Rain, but so far that’s never been officially confirmed. It’s been said it’s a song about anti-consumerism, or that it was based on a dream that Stipe had about the Rolling Stones. I always felt the song was about identity and choices and the world around you when making those choices. Is the person of desire the man or the woman, or both? In that way, maybe ‘Pretty Persuasion’ does tie into the water theme as this could be a statement on fluidity. Maybe that’s a stretch, but growing up in the South in a religious family in the ’80s and being bi, these lyrics couldn’t have rung more true. Wanting to be honest, but afraid of wearing it on your sleeve (being out), yet being told it’s all wrong, and goddamn, pure confusion. By the end of the song Stipe doesn’t even finish the last line, he lets “persuasion” trail off mid-word as one last sigh, maybe with exhaustion from all the tension between all of the options and deciding where to go next.

‘Time After Time (Annelise)’ is quite frankly the perfect closer for side A as both a slow-tempo acoustic number and as a song about time spent at home amidst songs about homesickness. The track starts off with hand percussion; nicely-balanced backing vocals; some of the clearest, most direct singing at this point in the band’s career; and this duelling electric/acoustic guitar mix, with each chorus feeling as if a new element is mixed in when it’s actually just a tiny bump in volume. ‘Time After Time’ would soon be a real signpost for the band as they would venture down this same path on Fables of the Reconstruction and Document, and really take it to another level on Out of Time. The song combines water references with a longing for home (“the girl of the hour by the water tower’s watch”), speaking about an Athens landmark water tower that was located on Chase St. and popular with locals at the time. I’ve heard so many stories about who the song is about or what it is about that it’s one of the cloudiest songs on the album for me, but I just try to enjoy it as a bit of a breather before things jolt back to life. It has its place on the album like most of the softer Velvet Underground songs, where it serves to remind you to take a moment. It’s the perfect song about life in a sleepy college town with nothing really to do and the places you find yourself that are away from everyone else, just with your select chosen few.

‘Second Guessing’ kicks off side B and is by far the track that gets the most grief when it comes to Reckoning, often critically considered a throwaway due to its simplicity and repetitive lyrics. This song comes to life not just by listening to it, but living to it; it’s a great track to perk you up while driving late at night, to get people off the couch at a party and moving on the floor, to pick at karaoke… it’s just fun, and with an album steeped in loss, remorse, homesickness, and, well, second-guessing, it is a much-needed uplift before what follows. Mike Mills does the heavy lifting on this track with a driving bassline and backing vocals that arrive slightly before each line of lead vocals. There is no connection to water on this track and it’s never been said who was doing all the second-guessing, but with Stipe’s lyrics on the previous album being so mysterious, you could almost imagine he is second-guessing himself, given how this album’s lyrics are so at-the-front and easy to understand.

‘Letter Never Sent’ leans towards the late-60s Byrds worship, which a lot of critics would use to describe a large part of the band’s early catalogue. It’s strummy, jangly, mid-tempo, with a simple direct drum beat moving it all along, and so much Mike Mills you could almost call this one a duet. Mills’s vocal perfectly lifts the song, allowing Stipe to add that extra bit of rasp and gravel. It’s a bit of a love letter to Athens and being homesick on the road, with lines like “vacation in Athens is calling me,” even though Athens is home. It’s another happy musical number with lyrics that contradict the tone.

‘Camera’ is by far the best song that Chris Bell and Big Star never wrote. The song is about a friend of Michael Stipe’s named Carol Levy who was a photographer that died in a car crash. In this one track alone, maybe more so than the rest of the band’s catalogue, they touch upon the magic of Big Star to leave enough room between the notes, the words, the vocals to allow the listener to join in in the reflection. These open spaces allow the listener to let the songs into themselves and place a bit of themselves into the song. This song is for their friend Carol, but almost anyone can place their own grief within it or calm their own grief from it, and that type of songcraft doesn’t happen that often.

‘(Don’t Go Back to) Rockville’ is one of the few tracks in the entire R.E.M. catalogue with lyrics fully penned by Mike Mills. Earlier versions of this song live were way more rockin’, but somehow the country-rock thing (from some stories told to be a bit of a gag or a fun take) with its honky-tonk keys ended up becoming one the band’s best singles. ‘Rockville’ was the second single released off the album and its country-rock vibe did well at the time on college radio and endeared the band to fans of up-and-comers Jason & the Nashville Scorchers and the Long Ryders. The story is that it was written about Ingrid Schorr, a classmate at UGA at the time and a bit of a plea to try to keep her from moving back home. Water is brought up again figuratively with the phrase “too far out to sea,” which is more to do with drinking away your sorrow than actual sea or water. It’s a song we can all relate to at some point in our lives, a plea to a friend who is moving back home where maybe things are easier, but you hate to see them leave and miss out on the friendship and new challenges.

‘Little America’ brings Reckoning to an end with a mid-tempo rocker filled with inside jokes and allusions to the nonstop touring the band was doing at the time. This song felt like a stream-of-consciousness word jumble before I ever went on tour, but once I did a few tours, I could see a whole entire world within each line. The line “another Greenville, another Magic Mart ” in the Southeast where every state has a Greenville and Magic Mart gas stations could make you feel as if you are never quite sure of just where you are. The “green shellback” the song references is their green tour van, which becomes a tiny home-away-from-home where you take turns getting sleep that’s never restful. Spending each day counting mile markers on the highway and each night on a different floor makes time kind of stand still despite constant motion; “I can’t see myself at thirty” feels like existing within the confines of the van and liminal spaces distorts the experience of the linear passage of days, weeks, months, even years. The title itself is an oxymoron: America is a huge, expansive place that stretches on what feels like forever with each state and region having its own flavour and identity. But on tour, you see mainly gas stations, hotels, and bars, often either chains or interchangeable spots that make it hard to believe you spent six or eight or more hours in a van driving all day to another place. Everywhere is different, yet exactly the same. Get up, eat, drive, stop for gas, eat, drive, load-in, soundcheck, eat, perform, load-out, sleep, repeat. There are moments in the song where the romanticism of a life on the road has started to fade and it’s more of a job, and relating to other random workers creeps in (“who will tend the farm museums?/who will dust today’s belongings?”). The line “Diane is on a beach, do you realise the life she’s led?” strikes me as a moment reflecting on all the things that happen in other people’s lives while you’re endlessly stuck on the road.

Reckoning wasn’t the first or last R.E.M. record I ever bought, but it is by far the one I’ve listened to the most and easily my favourite. At the end of the day, Reckoning stands sure on its own musically. The lyrics are easy to understand, the vocals are loud and clear, the music is confident with R.E.M. riding high off Murmur’s groundbreaking success, which honestly no one was expecting. Reckoning is an album from a band that had improved upon both their songwriting and their performance and formed an even tighter bond personally through relentless touring. It’s also an album that pulls the listener in with jangle-pop and earnest optimistic Americana, but it also gives us a look inside of how unsure things may have been with this newfound success and the life they were living (or maybe the lack of life) on the road. Reckoning, in the end, is also an account, a judgement, and a possible calculation that maybe the fame that was wanted so badly might have had a larger price in life than expected.