“I don’t think there’s one tune on RAM…” Ringo Starr commented dismissively at the time. “He seems to be going strange. It’s like he’s not admitting he can write great tunes.”

Released in Britain at the end of May 1971, and largely ignored by an unsympathetic audience that still held Paul McCartney solely responsible for the break up of The Beatles the year before, RAM was ridiculed. Immediately cast aside simply for seeming, “contrived”, born from some over-bloated sense of self-importance, and clothed in what many critics interpreted as merely the overly-pedantic ponderings of “domestic bliss”.

Rolling Stone magazine labelled it as, “incredibly inconsequential”, and referred to it, glibly, as not just irrelevant but, “monumentally irrelevant”. N.M.E. reviewed it as, “an excursion into almost unrelieved tedium”, adding that it was, “the worst thing Paul McCartney has ever done.” The Melody Maker critic weighed in with the observation that: “It must be hell living up to a name”, but wondered as to whether we perhaps, “expect too much from a man like McCartney”? Now though, retrospectively, the lambasted RAM is seen by many as the best album Paul McCartney ever made as a solo artist.

“I loved that record… because it was so simple,” Neil Young has revealed. “There was no attempt made to compete with the things he had already done.”

Fifty years on from its release, the album is now being held aloft beneath the spotlight and readily proclaimed a classic. Still simple but now “relevant”, “revealing” and “austere”, an endearing snapshot of the time, and of a singer’s circumstance. It has taken time, Lord knows it has taken time, but this collection of songs is now seen and loudly credited for those very same joke-filled, shuffling and spontaneous lyrics to a loving young family that had rescued a tortured man from unrelentingly dark hours, and from the bottom of a bottle.

“The break-up had its effect on me,” Paul revealed later. “I took to the booze. I was trying to recover in whatever way I could.”

Remnants of those dark and unrelenting hours still managed to seep through somewhere though, as thinly-veiled barbs and none-too-subtle digs at his one-time friends and now former bandmates being torn apart by money-fuelled arguments and the endless rounds of high court meetings; four friends now angrily and hungrily picking very publicly over the bones of their joint creation and legacy. And, as a testament to all of this, RAM now stands alone, although suddenly proud. As the sole McCartney album credited equally to both Paul and Linda McCartney. As a family’s scrapbook of lyrical snapshots from a life together, far away from all the madness and recriminations, and of an artist waiting to be rediscovered within the sanctity of a sprawling farm hidden far away from prying eyes in remotest Scotland.

“If Linda hadn’t got on his case,” drummer Denny Seiwell told Tom Doyle for MOJO magazine, “RAM never would’ve been made.”

“She just eased me out of it,” MOJO reports McCartney as saying of that time, “and sort of said, ‘Hey, y’know, you don’t want to get too crazy.’ And made me feel a lot better. And then I moved again into music therapy, which was RAM…”

With each song, cathartically penned and reworked between the daily chores demanded by a working farm and a young growing family, and demoed at night, single-handedly, in a homemade studio that was little more than a simple “lean-to” propped up against an old out-house but containing a favourite four-track machine, McCartney began to rediscover his joy. He began to sober up, “to heal”. He began to emerge from the shadows of The Beatles, from the ties that bound him to John, George and Ringo and from the debris of all the legal wrangling that had threatened to bury him.

“I suppose I was just letting myself be free,” he would admit later to Tom Doyle.

In New York, fulfilling an ambition and finally managing to record in the U.S., something The Beatles had never done, and working with a new band comprising of David Spinozza, who had been recruited personally by Linda, Hugh McCracken and drummer Denny Seiwell, who would later join Wings, the recording sessions for RAM began on the 18th October 1970, and saw everyone enveloped within a family atmosphere, Paul and Linda’s daughter Mary content in a playpen installed in the control room of Columbia Record’s Studio B.

“Immediately what dawned on me was how good the songwriting was,” Spinozza tells MOJO.

“It was some of the best stuff that he did – definitely since leaving The Beatles,” Denny Seiwell revealed to Classic Rock.

The album opens with the track ‘Too Many People’, throughout which McCartney’s feelings begin to form and take shape, rising bitterly to the surface and aimed specifically towards his one time writing partner, John Lennon; the track famously beginning, apparently, with the words, “piss off”, sung in a whisper just above an otherwise slightly psychedelic intro, although now, Paul insists that he actually sings, “piece of cake”.

“And hey,” he tells Doyle, “come on, how mild is that?” And of the lines, “Too many people preaching practices…” and “you took your lucky break and broke it in two”?

“I felt that was true of what was going on. ‘Do this, do that.’” Now it seems as though Paul would not have cared so much if all the “preaching and the practices” he saw coming from those advising John, George and Ringo, namely Allen Klein, had been wise. But, according to The Beatles’ former business associate, Peter Brown, Lennon strongly believed that several songs, including ‘Too Many People’ and ‘Dear Boy’ had been aimed directly towards him and Yoko Ono, whilst both George and Ringo interpreted the song ‘3 Legs’ as attacks directed at them and John, especially the lines, “My dog he got three legs, But he can’t run”, and “I thought you was my friend, But you let me down”. The small image of two beetles, strategically placed on the back of an otherwise simple album cover, would only help to add to all these pent-up feelings of frustration, mistrust and recrimination, to what fans read and heard as barely hidden innuendoes.

One track that McCartney insists had nothing to do with Lennon though, is ‘Dear Boy’. Instead, he says, it was written to Linda’s first husband, who, as Paul sings, didn’t realise quite, “how much you missed”. But, the songs had been pored over endlessly by former bandmates, fans and critics alike, and the interpretations and lasting first impressions had been made, rightly or wrongly. And it was the songs ‘Too Many People’ and ‘Another Day’, the single released just before RAM, that Lennon would soon respond to directly, his track ‘How Do You Sleep’ famously including his own bitter observation that: “The only thing you done was yesterday, And since you’ve gone you’re just another day”. There would be no disguising who that was aimed at.

“Those freaks was right when they said you was dead, The one mistake you made was in your head.”

For Paul though, RAM was a way of making sense of all the conflicting emotions, and of working through them, finally ridding himself of all the confusion and frustrations. “Like I say,” he would explain to Tom Doyle, “that was my saviour.”

Ram is now seen as a more highly polished and professional offering than the album that had come before, McCartney, and with much less of the “homemade” or “rushed” feel about it, even including the New York Philharmonic who added full orchestrated flesh to the singles ‘Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey’ and ‘The Back Seat of My Car’. Still minimalistic and simple, according to the various reviews that mark this anniversary, but now it is revered as tuneful and heartfelt, as a classic album from an artist cheerful and seemingly fulfilled, even in the midst of all the adversity.

“Looking back at it now, like a lot of things in retrospect,” Paul admits to Classic Rock, “it looks better than it looked to me then.”

RAM would reach number 1 in the U.K. album charts, and number 2 in the U.S. Billboard 200.

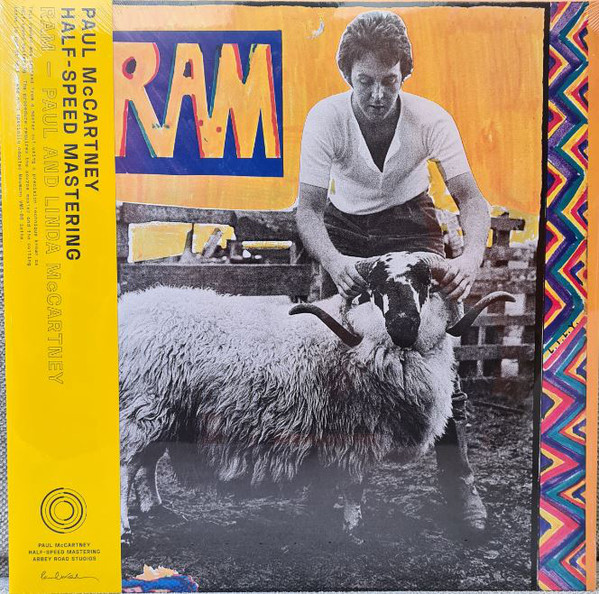

The Limited Edition 50th Anniversary Half-Speed-Mastered Vinyl of RAM is out now.