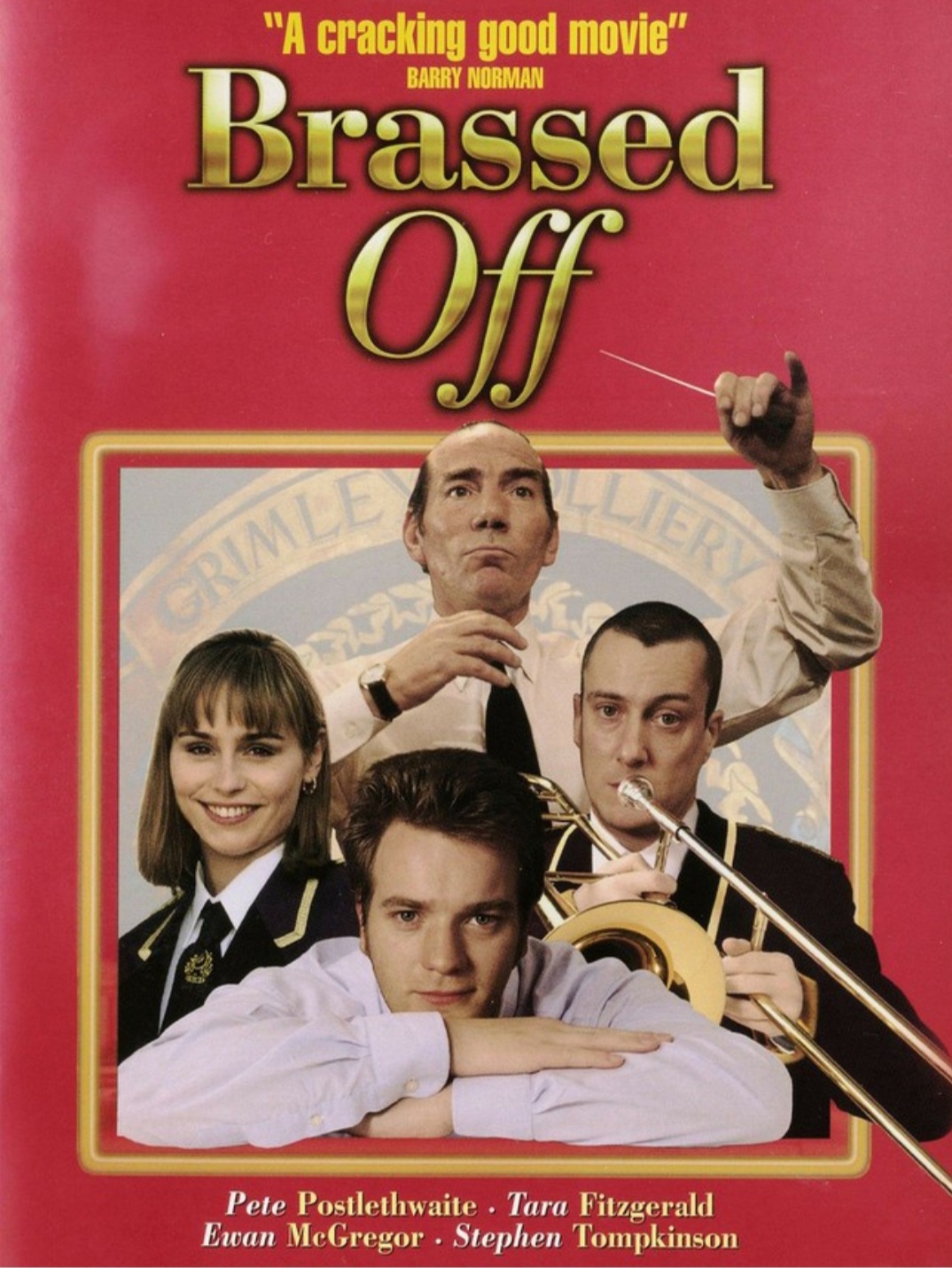

It’s astonishing to think that Brassed Off – arguably the finest British film ever made – will be a quarter of a century old in a few months time. So I was delighted when its director, the exquisite Mark Herman, agreed to talk to God Is In The TV about brass bands, box office and bellboys…(NB, if you haven’t seen Brassed Off before, please, please only watch the trailer and not the other clips. It’s an incredible film and you owe it to yourself to watch the whole thing properly!)

God Is In The TV: I first saw Brassed Off with my then girlfriend at the cinema in 1996, by accident really, after the film we’d gone to see (Independence Day, if memory serves correctly) was full up. It was one of the greatest strokes of fortune I’ve ever had, as it has been my favourite film of all time ever since. It seemed to take some of the critics a lot longer to latch on to its brilliance though, but happily nowadays – 25 years on, it appears to be roundly revered as a ‘British classic’ – it’s rare to see it get anything less than a rating of 5 out of 5 these days, and rightly so. At what point do you think you realised you were creating something very, very special?

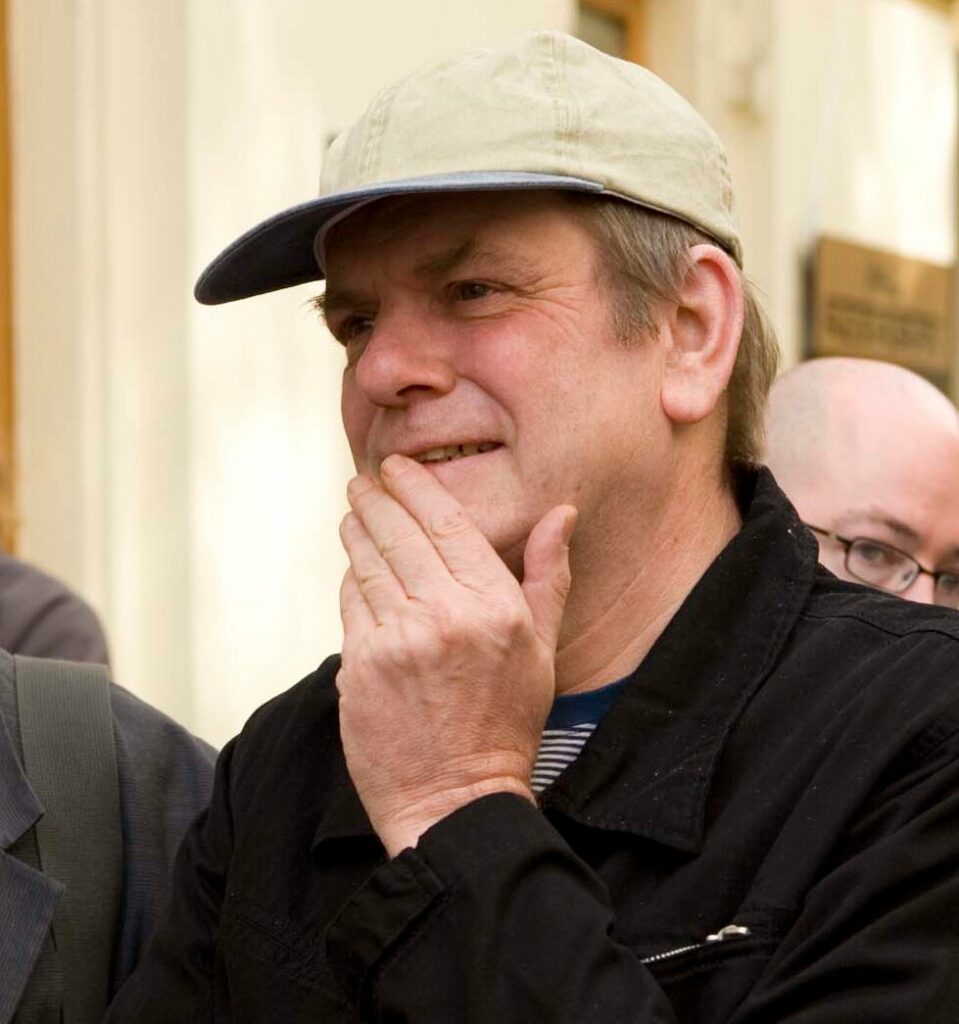

Mark Herman: Good choice to dodge Independence Day even if only by accident of its popularity, but then I’m biased. Interesting that you noted how long it took some critics to “latch on” to Brassed Off, but I’m not sure that’s altogether true. It was actually the general cinema-going public that took a while. We had pretty decent reviews from the off when the film first came out but the box office on that first weekend was weak, to say the least. I’d had an experience on my previous film, Blame It On The Bellboy, which Disney released first in America but which had similarly poor opening weekend numbers and which, as a result, they ‘pulled’. Two years’ work and it lasts in USA cinemas for maybe three nights? I was very fearful that Film4 would do the same here with this. Instead, thankfully, they decided to risk it for another week. Now most films open with their best figures that first weekend, then drop off in the midweek and then probably come back up but have a thinner weekend number than the first. But Brassed Off behaved strangely. More people went to see it during the midweek, and then the 2nd weekend was strong, and that was followed by another big midweek. Despite those good, sometimes great reviews, they weren’t enough to get ‘bums on seats’ to start with, but what became so clear was that the word of mouth on the film was extremely strong. I suspect there was a lot of “it’s so much better than you’d think” going on. The poster erroneously indicated it was a fun comedy, misleading, but I think what happened was that those going to see a comedy found they got something extra, some serious bite, and anyone going for the politics maybe got a laugh they hadn’t expected. Also, it was always a hard pitch – a film about suicidal trumpet blowing miners – and I think that was possibly what people thought the film might be, so didn’t bother – (and indeed probably why you and your girlfriend preferred to try and see Independence Day) – but when there was just enough people going to generate that very positive word of mouth, that’s when it took off, and in some places didn’t stop: It played in one cinema in West Yorkshire for a year, and even then we had to stop it because the video was coming out.

More specifically, in answer to your last question, there’s a big difference between thinking you’re making a hit and thinking you’re making something special. We all – cast and crew – a few weeks into shooting, realised we were making something very special. The more time we spent in Grimethorpe, working in a town that had such similar experience, and with people who had lived through those closures, the more obvious it was that we were making something that mattered. It never really crossed my mind it would be a hit. I thought a few people within a 5-mile radius of Barnsley might understand and enjoy it, but then maybe quite quickly forget it, so it’s always been a hugely rewarding and surprising experience to see it become so big, especially around the world, and – more importantly and tellingly – to still be appreciated quarter of a century later.

Many of the actors in Brassed Off gave what I would consider career-best performances, none more so than the towering contributions of the late, great Peter Postlethwaite and the amazing Stephen Tompkinson. As director, how much did you influence the way they played those roles, and were you, yourself, surprised at just HOW powerful their performances turned out?

Despite a little encouragement otherwise, I was always keen, when casting, not to choose some ‘star’ name that would put the whole thing out of kilter. I wanted it to be a genuine ‘ensemble’ as I thought the audience would buy it more. Hence the cast list we ended up with – they are largely fairly well-known faces, but not ‘stars’. Pete Postlethwaite was a fairly big name (though nobody seemed able to pronounce it). Ewan McGregor was about to be a star – I’d seen glimpses of Trainspotting but it hadn’t hit the screens yet, but he and the others were I suppose all faces people knew from TV, Jim Carter, Phil Jackson, Tara Fitzgerald etc. Sue Johnson was probably the most famous face in town at the time due to Brookside, but still not that big star that would jeopardise the balance of the ensemble I was trying to form. Tara Fitzgerald also hadn’t been too high profile before Brassed Off. I remember an audition session I did with her, Catherine Zeta-Jones and Kate Winslet (and Film4 being more than a little astounded that I had gone for the least famous name). Pete Poss, I thought at the time, and still think now, was the best British actor of his generation. He had been encouraged not to do this film (indeed not to touch me with a bargepole after the failure of my previous film), but he went against that advice simply because he loved the script. Going against that bargepole recommendation, he met with me for a quick lunchtime pint to discuss the project and eleven hours later he was fully on board and we were very much in love. When I met with Stephen Tompkinson he couldn’t believe I wanted him for the role of Phil, and not the slightly lesser one of Andy. Stephen had never done a film, but there was just something about him that I saw in his TV work, even somewhere underneath the comedy of Drop The Dead Donkey, I just had the feeling that he could deliver a performance that I wanted for Phil. I could imagine he and Pete having a chemistry as father and son.

As far as ‘how much did I influence’, I think most of that directorial side of things is down on the page, in a way. All the cast, I like to think, grasp just from the descriptive part of the screenplay what is required. I have always felt, the most crucial part of my work as a director is in this casting process. You need to know you’re going to get on with them, but you also know, or at least you should, that these actors are of a professional standard, below which, you wouldn’t cast them. You meet them, they’re great at what they do, they understand the script, they usually just come up with the goods. Any influence from me, on the floor, is literally, usually, just a tiny tweak here and there. Turn it down to 5 or turn it up to 8 etc. Stephen Tompkinson is a good example. Maybe he was surprised to get the role, but that showed the trust I had in him, and I suppose – if this doesn’t sound too wanky – his performance was a repayment of that trust. Not one of that cast needed the loud hailer directorial approach, they just needed the odd raised eyebrow or thumbs up, a nudge in a certain direction, and that’s what they got.

I watched your debut full length feature, Blame It On The Bellboy, when it came out, and, despite its somewhat disappointing critical response, I enjoyed it, but I must admit, the leap from that film to Brassed Off was gargantuan. There was a gap of about 4 years between the two films. What happened in the interim that led to you making such an incredible movie on your second attempt?

I suppose I covered some of this in earlier answers, but after ‘Bellboy’ I couldn’t get arrested. I wrote a few what I thought were commercial ideas and screenplays, but nobody seemed remotely interested. I had just moved to London, and for those first few years after ‘Bellboy’ had had more children than pay cheques so things were getting a bit hairy. Advice to me at the time then, and still probably the best I ever had, was to stop trying to write things that I thought would be commercially attractive and instead just write something I cared about.

Blame it On The Bellboy was a farce comedy – historically very difficult to succeed with on film. A Fish Called Wanda had been one of those rare successes, and at script stage on ‘Bellboy’ the producer of ‘Wanda’, Steve Abbott, came aboard and I suppose that is how it got made and how – another rarity – I got the chance, first time out, to direct my own script. The Hollywood studios were terrified of missing out on the next ‘Wanda’, and with Steve on board and it being another comedy farce that he was behind, there was as much of a (reputational) risk in rejecting us as there was of a (financial) one in backing us.

But as I say, after it was such a critical flop, it was nigh on impossible to even get anybody to read the screenplays I wrote next. And that advice – to write something I care about – was easier said than done as for a good while I couldn’t find anything I cared about! And in the end it was a complete fluke of a road closure that ignited things. Driving back south after a trip north to see my parents the A1 was closed for roadworks and there was a diversion across to the M1 which happened to take me through Grimethorpe. This was an area I knew quite well in an earlier life when I was a bacon salesman, and I was astonished to see how the place had been killed by the pit closures. The miners’ strike was never off the TV so I was fully aware of that, but the actual closures, and the devastating effect they had on those communities, that sort of stuff never made the news. Shops that I used to sell bacon to were all boarded up, the knock-on effect of the closures on all surrounding businesses was horribly clear, these once thriving towns were now ghost towns.

So there was something I cared about, and the more I delved into any form of research the more I cared. I wrote a film treatment but it was a bit dour and I thought, I’m sure rightly, that it would never get made, and it was only – again pure accident on another car journey – I heard a report on the radio about a band up in the North East having to pack in because nobody could afford the subs any more, and that gave me something to hang the whole narrative on. And although there’s nothing funny about brass band music, it did actually provide a platform for a flavour of some humour. (NB, advice to prospective screenwriters – don’t just sit in the car listening to the radio waiting for ideas to fall on your lap, it doesn’t always work like that.)

So, in answer, I suppose the main “thing that happened” was a realisation that, yes, writing is a hell of a lot easier, and much, more meaningful, and rewarding, when you’re writing from the heart than trying to follow some script-writing manual formula.

There is no other film I’ve seen as many times as Brassed Off. If it happens to be on when I’m channel hopping, I still stop and watch it, even though I’ve seen it a good 20 times (at least) and own the DVD. I don’t normally watch ANY film more than twice, but no matter how many times I’ve seen it, I’m still an emotional wreck after every viewing, yet for all its gritty realism, there are scenes of pure joy too, and I get the impression that it was an absolute blast to make! How close to the truth is that and what is your happiest memory of filming it?

Important thing to know about film-making is that if you’re “having an absolute blast” making one there is absolutely no guarantee that that means you’re making a successful one. In fact, it’s a pretty good bet it’ll be the opposite.

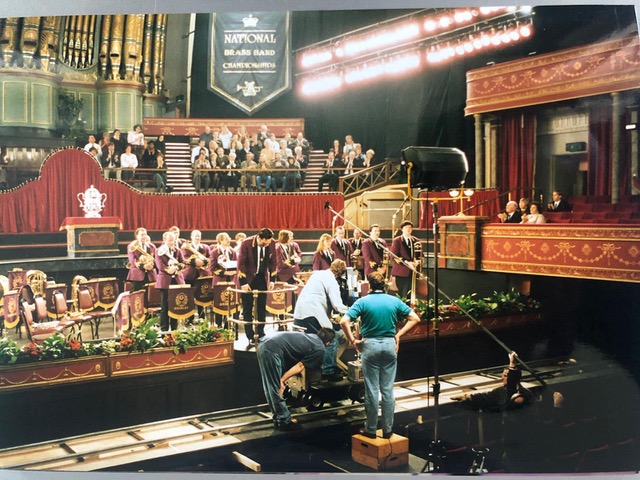

I always say film-making is 20% misery but actually the other 80% is torture, and I’d probably say the same about Brassed Off, but that’s just a misery-guts director with too much responsibility on his shoulders. What was true about this film above all others, though, is that the atmosphere and spirit on set was just amazing. We had a pretty much entirely southern based crew (and cast) up in South Yorkshire having their eyes opened, wide, and because of that, they took the project hugely to heart. It was a very emotional shoot. After at first being held at a distance by sceptical locals, once they knew what we were about, and actually on their side, we became very warmly welcomed, and the relationship between film circus and the community became very strong. The bind between we film-makers and the band itself is still very strong now, quarter of a century later.

Yes, all right, I admit we had plenty of laughs. But I think my favourite memory is again, one to do with the spirit of those involved. The ‘Danny Boy‘ sequence outside the ‘hospital’ (a college building in Doncaster), went long into the night, way, way too long, but the fact that those real-life band members, who all had (proper) jobs to go to the next day etc., were willing to carry on, stoically, into the small hours, will be an abiding memory. It was a moment when we all realised how ‘together’ the whole production was, and how we were making something that really mattered.

Probably the actual happiest memory in the whole process was when the film won an audience prize at the Emden Film Festival in the industrial north of Germany. It came at a moment when we weren’t at all sure we’d made a film that would ‘travel’ internationally, but we got a standing ovation that we just couldn’t stop.

The only people I’ve ever met who DIDN’T like Brassed Off were Tory voters, which only makes me love it even more. It’s 13 years now since The Boy In The Striped Pyjamas (you love making us cry, don’t you?!!). Are you tempted to make another very political film, given that within six months of Brassed Off coming out, we finally had a Labour government (of sorts) in power for 10 years? I mean, looking at our present incumbent, if ever there was a time when a change in government were needed…

I wish. The kind of film I like, or liked, to make, those mid-budget level films, are increasingly hard to get financed, never mind the politics, that just makes them even harder. I’ve written a number of screenplays since Boy In The Striped Pyjamas which you might think, after that film’s international success, would find the backing no trouble, but they haven’t. The industry’s changed, and I don’t think for the better. It’s all blockbuster franchises now, or micro-budget, nothing mid-range. Nobody is taking risks any more, which leads to pretty dull fayre on offer all round.

Brassed Off seemed to have been marketed in the US as some kind of romantic comedy, which I thought was very odd. Don’t get me wrong, obviously the Andy/Gloria subplot was important and both Ewan McGregor and Tara Fitzgerald were wonderful, but it was far from the central theme of the film. I’m curious as to why it was promoted that way Stateside?

That nice Mr. Weinstein, who sold it in the U.S., for all his horrific ‘faults’, was actually at that time recognised as a bit of a master at marketing, but I think he got this one all wrong. It was a hard enough sell in America as it was, but deceiving the public into thinking it was a romance was not going to help anything. He also stuck an exclamation mark on the title, which also implied sort of wacky comedy. We argued over that exclamation mark for weeks. He did in the end admit he got it wrong. He saw the huge success of The Full Monty tear across America but even then all he said to me was “If only we’d got the band to take their clothes off, we’d have had a smash hit”. Though I didn’t know the band that intimately, I’m pretty sure that wouldn’t have been the case. Robert Redford opened Sundance with it, successfully, to an appreciative audience that fully understood it, so it was strange that Harvey didn’t have the confidence to sensibly build on that.

To me, everything about Brassed Off is perfect – the acting, the cinematography, the costumes, the vibrant colours, the powerful imagery, the political stance, the supporting cast and so on. When you watch it back, what would you say you are most proud of about it?

Film is totally a collaboration, and that is what I’m most proud of in Brassed Off. All the departments you mention coming together so well. Not common.

How much of a springboard was Brassed Off for your career? Your next film, after all, was the hugely successful (and also brilliant) Little Voice…

Harvey Weinstein again. After Sam Mendes left as director on the soon to be Little Voice, Harvey (and Liz Karlsen, producer) felt – having I presume seen rough cuts of Brassed Off – that another Northern English music related film needing a script and a director – why not try Mark Herman.

Did you ever see the stage musical of Brassed Off? And if so, what did you think?

Yes, I’ve seen it a few times at different stages. I saw it when it opened at The Crucible in Sheffield, but you could put a can of beans on stage there with a label saying ‘Labour’ and they’d love it. I felt then that it was trying actually to stick too close to the film, and that Paul (Allen) the playwright should be braver with it, and try a few things out. It did develop well and I’ve thoroughly enjoyed it some times I’ve seen it. A crucial matter, often, is the casting of Gloria – do they get a great flugel player who can also ‘act a bit’, or a great actress who can also ‘play flugel a bit’. The former is marginally better!

More recently, Harvey Weinstein (again), before he was otherwise detained, went on and on at me to let him make a stage musical of it, sort of in the realm of Billy Elliot I suppose, but I said no. ‘No’ is not a word he is famed for understanding, so it was a long process to put him off the idea. I mean, the notion of a song and dance being made about the closure of the pits? I wanted to be able to walk down the street in Grimethorpe again, and live!

Phew. I think we can all breathe a sigh of relief about that, readers! There is nothing that needs to be added to what is, pretty much, a perfect film. If you never saw it at the time, I would encourage you to make amends right now, in the year of its 25th anniversary. I’m almost envious if you’re seeing it for the first time!

Thanks to Mark for giving me such a ridiculously brilliant in-depth interview!