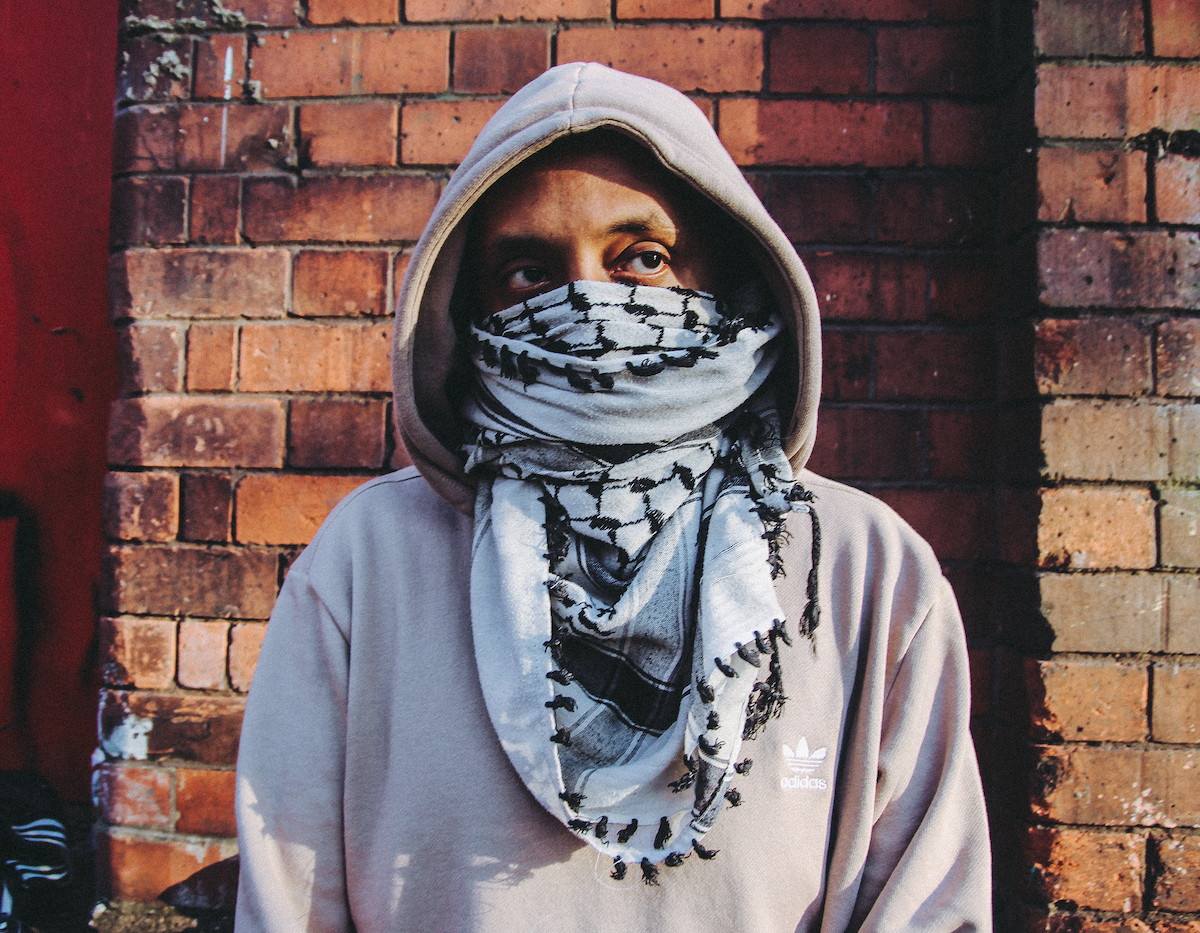

‘Winter of Discontent’ is the mysterious, devastating debut album from British/Somali poet, rapper and neofolk singer-songwriter Knomad Spock.

Born and raised in Hull and now residing in Cardiff (following brief spells in the Middle East, Bristol, London, Thailand, East Africa and Andalucia) he takes his name from the restless spirit that drives him and fuels his creativity, curiosity and artistry.

Recorded in Scotland at the idyllic, isolated St Mary’s Space studio, his debut album is an exploration of alienation and fluid identities, bridging gaps between forms, cultures and musical genres.

Produced by Jamie Smith, the album melds many different influences and textures – sounding at various points like Kid A-era Radiohead, Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians, Elliott Smith, contemporary classical, and Portishead – but always sustaining its own unique mood and voice.

It’s a meditative, minimalistic, other worldy piece of work that’s shrouded in Sufi mysticism – a sincere dream-search for love and meaning that seems to capture something of the prevailing cultural mood of our times. In fact, it’s probably one of the best and most intriguing albums of 2021 so far.

I caught up with Knomad Spock for a chat to find out more about Winter of Discontent and the experiences that went into making the record.

You’re a nomadic spirit – where are you at the moment?

I’m based in Cardiff at the moment. I’m really itching to go back to Hull, to be honest. I love Cardiff and it reminds me of many of the things I love about Hull. Just down-to-earth people, really funny, real working class, communitarian spirit underneath it all. Might be time to go back to the North, I don’t know.

The album sounds amazing and Jamie Smith’s production is unique. What was the recording experience like?

Jamie and his wife Charlotte, they’re really just amazing spirits and very artistic. He wanted a space that could recreate a kind of Abbey Road natural reverberation and acoustics. The thing is, it was just pure fluke.

I was staying in a cottage on the island of Lismore, just to get away, clear my head a bit, think about next moves in life in general. I had no real intention of recording this record at all. And never thought that I’d have the instant chemistry with Jamie, creatively.

It was really random. Did a search, found this place, it was only a ten-minute ferry, the port was 10 minutes from my cottage on Lismore, the ferry was a 10 minute ferry, and then he lives five minutes drive from there.

Sounds serendipitous.

It was just amazing, man. I’ve got a lot of hang-ups about my guitar playing, so the first conversation was ‘I’ve written these songs, I’m not even sure if some of them are songs or not cause they feel more like sketches, but I don’t have the confidence to play them right all the way through on a recording, and have it sound good, you know? Would you mind recording parts if I can’t nail it?’ And he was like ‘yeah, guitar’s my instrument, don’t worry about it‘, just, you know, really cool about it all.

I couldn’t recommend it any more highly, really. I said to Jamie when I was coming down, I was like ‘listen man, I’m gonna make sure that everyone I know comes up here to record.’

Do you know Tom Algorithm, the minimal techno producer from Cardiff? He’s gonna do some remixes of the songs. So he asked for the stems of the tracks without any reverb on them, and Jamie had to explain ‘look, I don’t use reverb – what you can hear on the stems is actually the sound of the room‘.

Wow that’s mad.

Yeah, crazy. He just knows that space inside out, and it’s a very interesting space, man. He’s figured out where in the room to put the microphone to get a particular sound. I’ve recorded in loads of places over the years. No-one I’ve ever worked with comes close to him. He’s on another level, really is.

There’s a real warmth to the record, which probably comes from recording in that space and from that collaborative energy too. Had you written the songs a long time before?

A bunch of them, yeah. Been tinkering about with some of them for years. But two or three of them were written within a 3-month creativity burst. I went to Thailand to learn Muay Thai boxing. I ended up getting injured really early on, basically, cause nah, I can’t be doing that. Dunno what I was thinking!

So I ended up going to this guitar shop and loaning this absolutely haggard guitar which was my companion for the rest of the time I was there. It was awful to keep in tune, but I wrote a couple of songs, I wrote ‘Papillon’ when I was out there. But nearly all of them were transformed while I was in Scotland.

Little ideas would come out of nowhere, I’d just come up with a riff, and I’d be like ‘oh this would work at the end of this’, just random things like that, and then Jamie transformed the arrangements again completely, and even the concepts behind some of them.

Jamie is classically trained, isn’t he, so that’s two different approaches coming together.

Yeah, man. But, interestingly, cause I’ve played in bands with people who’ve been classically trained, and Jamie’s got an avant-garde training as well, he’s got a masters in avant-garde composition. So you’ve got to the point where you understand the form and the structure of music, but now you know how to break the rules as well.

So, with him, there were a handful of things he said to me that were so liberating for someone who doesn’t have the musical literacy. Like for him the most important thing in music’s not melody, it’s rhythm. And that to me just means you can be very uncomplicated with what you play, if you figure out a nice little rhythm to it.

So had you been performing the songs before this, or were you not really performing live? What kind of bands were you in before you did this?

I’ve been in hardcore punk bands. I’ve been in hip-hop bands, DJ-MC combinations. I love playing live, but in the last 10 years I’ve felt like I’ve had to put that dream to bed a bit, cause I’m quite an obsessive person really, and I felt like I had to be obsessive about my family and my daughter.

There was a way to be more moderate about things, if I was like ‘I’m not gonna stop doing the music, I’m just not gonna be as intense about it’, you know what I mean.

But I sold my guitars, for a start. Needed the money – it wasn’t just because of being a father. But finding a middle ground – I’m trying to find that middle ground now.

Was it during the first bit of coronavirus that you went up to Scotland?

Yeah. I was there end of Feb, early March. We did 4 days of recording.

4 days, that’s amazingly quick really. I suppose that’s a sign of inspiration.

I think so. I mean, I write poetry as well. And all the poems I’ve written that have connected with people, the minute you write it, you’re like ‘where did that come from?’ You’re aware that there’s been a moment of inspiration that you’re very fortunate to have had, and you’re not always sure whether it’s entirely from you, your psyche, or externally. It’s a bit of a crazy process.

But that whole week was like that. It was really strange. And then we just trusted, and tried to get out of the way of, the process. I didn’t say no to any suggestion that Jamie made. ‘Poles’ was a straight-up Dylanesque folk song, and I needed to write in that way to get those kind of lyrics to come.

And then I played it to Jamie, and he was like ‘well, let’s let the music follow the lyrics’, and then he designed this entire soundscape and transformed the music. It wasn’t what I went there with.

But in the moment, it was like ‘just trust him. It’s gonna be ok.’ And it sounded brilliant. Those moments of inspiration, you’re very lucky to have them – don’t get in the way of it. Just let it happen, kind of thing. Take a step back, and see what happens.

It’s very refreshing to go to a new place, isn’t it. It’s such a privilege and an amazing thing.

It really is. Which brings me on to this government…

That’s a whole other conversation isn’t it!

It is a whole other conversation, and a really quite tragic one, haha. Britain’s always had problems. It’s always had things that it’s needed to fix, reconcile. But there was always this forward-facing pragmatism about Britain and the British, which has gone. And nothing could have prepared me for this complete spiral into just…nonsense.

I mean, when you’ve spent a bit of time in Europe, as well, things get really interesting. I love Germany, and I love the Germans. I’ve had a few friends who studied there, and any student house I was sat in, it’s how I imagined University would be.

And I was always the weird kid at Uni – so I’d be there, and I’d be saying ‘right, the revolution – let’s get going’ and they’d be like ‘what’s wrong with you?’ with their £5 sandwiches they’ve bought from the student canteen.

And I’m like ‘but we’re supposed to be students!’

Become a centre-right predictable Tory when you’ve hit 40, I’ll forgive it then. But the energy of the society for change has to come from the youth. A society loans that energy, it borrows that energy from its youth. Even if the youth burn out and conform later on, fair enough. You’ve come out of the gate conforming. We’re hopeless. Germany, though…

But you know, the compassion part. If you can’t have compassion for someone else, right, you can’t have compassion for yourself. And that’s what’s happening. People are clinging on to the illusion that they have been taught to tell themselves to get through the banality of their existence, right.

And it’s banal because you go to work in a system that doesn’t respect you, doesn’t care about you. Keeps you tied into debt and fear of losing what little you have. The work you put in goes to support a system that hates you.

I lost years and years in an existentially caused depression, I was just like ‘the world is so horrible, why is everyone so horrible to each other? Why? What is this? Where is this coming from?’

And actually, the last couple of years, when everyone else seems to have been moving to that now, I’m feeling quite optimistic. I’m feeling that there are more people who are just as dismayed about the state of things, who are quite happy to live in a world where they forego some of their rights and privileges and wealth so that everybody else can have a better crack at it, and want to start from a position of empathy and tolerance.

If that’s the case, we just need to get that together. I think enough of us have to say, in our art, ‘we see what’s going on, we’re not cool with it.’ But history goes through these cycles, and hate never wins. It never wins.

Art is the best way to get through to people, I think.

I think so, man. I feel like there’s another…I think what happened in the 60s and 70s, when there was that massive blossoming of class and collective consciousness, right, liberation of women, of gender, of who you wanna be as an identity, as a person. Who you wanna love, who you wanna fall in love with.

All the dogmas around that got looked at for the first time, and people said ‘I’m not going to Vietnam, to die so you can make money. I’m not gonna get into some patriarchal marriage cause that’s what expected of me as a woman’. They didn’t see that through.

It was a failure, wasn’t it. But that is what we need. Tiny revolutions in people’s heads. Nothing to do with party politics or grand gestures, it’s just these small mundane revolutions that we need, I think.

I agree. And how do you do that? You do it with a photograph, a painting, a poem, a song, you do it with a small act of generosity that no-one will ever know about except for you and the person who received it – outside of a shop, or a complete stranger in the street needs a hand, and you take that 30 seconds out of your life to do something for somebody that they’ll be telling people for the next two weeks – ‘it’s not all bad you know, a complete stranger did that for me.’

Stuff like that, they’re the little revolutions we need. The big revolutions – that’s out of our control. But what’s in our control is – what do I have to offer, and how can I apply that energy? And I think it’s artists who do it more than most, really.

Yeah I think so. It can be hard, though. But you’ve just got to keep doing it.

You know, I was talking to somebody today. He was saying that Tom Waits said he’d exorcise his demons, but he’d lose his angels as well. You know?

What we offer, what art offers, what we hope to offer one day, but what art has offered the world since day one, since cave paintings, since the very first person to sing, is light at the end of the tunnel.

We’ve got to be in that tunnel, though. And I think that’s what people don’t see about the whole process of being an artist, a lot of the time, the only reason you can shine that light at the end of the tunnel is, you know the tunnel a bit too intimately well.

‘Winter of Discontent’ is out now