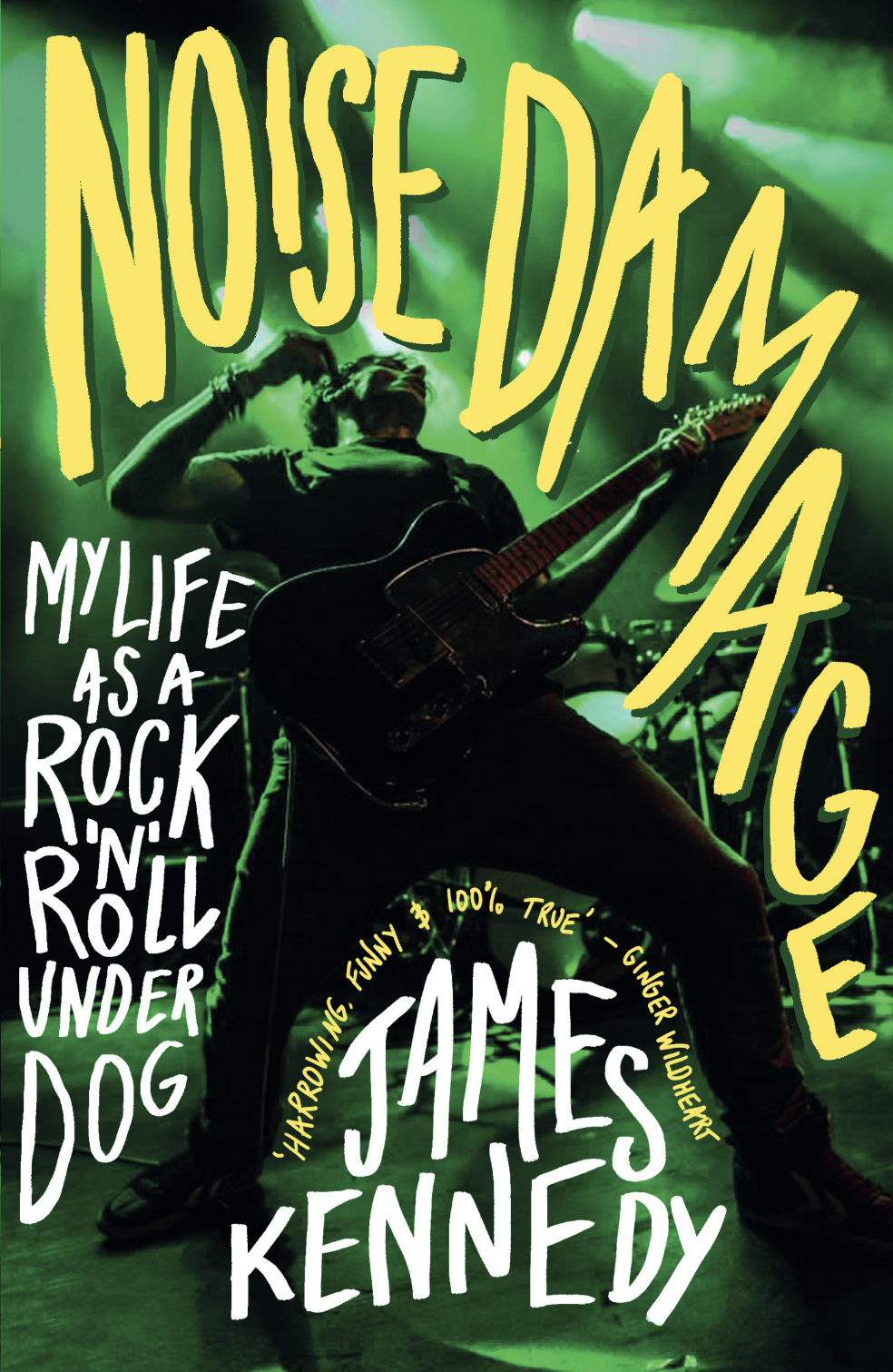

It’s the story of a half-deaf kid from a tiny, remote village in South Wales who was hailed as a genius by the UK’s biggest radio station and headhunted by major record labels, only for the music industry to collapse. It crashed hard, taking with it an entire generation of talented artists who would never now get their shot. CNN called it ‘music’s lost decade’.

Along the way, there are goodies, baddies, gun-toting label execs, life-saving surgeons, therapy, true love, loyalty, hope, breakdowns, suicidal managers, betrayal, drummers and way too many hangovers. James Kennedy shows that the best lessons are to be learned from good losers. It really is all about the journey.

Part memoir, part exposé of the music world’s murky underbelly, Noise Damage is emotional, painfully honest, funny, informative and ridiculous. It’s also a celebration of the life-changing magic of music.”

CHAPTER 6

WHY DO WE DO IT?

There is absolutely nothing that compares to the rush of performing live.

Those who have done it will know what I mean. For those who haven’t, it’s impossible to faithfully describe it, but I’ll try.

Imagine if you will:

The subtle anticipation begins days before the gig itself, always at the back of your mind that ‘it’ is coming. The preparations have been made, rehearsals done, guitars re-strung, equipment packed, sick days blagged, directions and load-in times sorted, and mates nagged to come. When the fateful day arrives, the entire day revolves around the gig. After meeting up at someone’s house (almost always the drummer’s, for reasons still unknown to science) to cram a truckload of heavy equipment into the back of someone’s hatchback, the road trip begins.

Side note: despite the popular misconception that musicians are a bunch of work-shy hippies, most of a musician’s time is spent lugging, lifting, and packing heavy equipment. And we’re experts at packing – if you want to know how to get the back line of Wembley Stadium into the back of a Fiat Punto, ask a musician. Anyway, you are now officially off duty from the real world. Your only responsibility in life is to make it to the gig, kick ass and be awesome. No boss, no dress code, no fixed abode, no rules. Excitable and preferably distasteful banter abounds, and after battling your way through hours of traffic, crap service station sandwiches and the bass player’s Eighties metal playlist, you arrive.

Everyone else is sitting at work, and yet here you are ramping the pavement outside the Dog and Whistle on a cold Tuesday afternoon in Camden, not giving a fuck.

The frantic ‘load in and move that damn car’ routine begins – which means parking five miles away in the nearest residential area and getting lost. Heart already racing from the manic hurtling of amps and drumkits down dark, dingy stairwells and the panicked re-parking of your poor, buckled Fiesta, you now enter the calm before the storm. Back at the venue, you pick an amp to sit on and you wait. Every venue is awesome. Despite being a cold, dusty shit-hole that smells of sweat and bins, with sticky floor, peeling walls and electrics that will kill you – to you, it’s a thing of beauty, history and wide-eyed wonderment. A thousand stickers of previousvagabonds adorn every visible surface (some you recognise) and in this quiet, mechanical light of day, the venue is a world apart from the bouncing, beery dungeon of dreams it will become in a few hours’ time, illuminated by stage lights (the ones that work). And speaking of lights, they’re hot. Real hot. Performing under them takes practice in and of itself.

For me, arriving at a live music venue is like the smell of a new book.

And just like the opening pages of a new book, I see that empty room as a place of imminent new adventure and exploration. As the other bands begin dribbling in and the mysterious ‘sound guy’ begins huffing and tutting at stuff, the excitement starts to creep in again. At this point, it’s all about getting a soundcheck – because no one wants the dreaded ‘line check’, which means the sound tech will be getting your levels right during your set and no one will hear the vocals until the third song. If you’re lucky (and pushy), you’ll get a soundcheck – which means setting up all your equipment and doing a run-through – but then there’s the problem of what to do with your gear. The stage is barely big enough for one band – and there’s five on the bill tonight! Creative stacking of amps and sharing of drumkits helps but the ‘stage’ area is now reduced by about eighty per cent – meaning that all your awesome rock stagemanship will have to be confined to a square foot. You’ve now got half an hour until the doors open, so you stuff another plastic corner-shop sandwich in your gob and getbattle-ready.

The question of whether anyone will turn up only feeds the adrenaline and excitement brewing within you as the lights go down and the first band blasts its way through an awful-sounding combo of line check and empty room reverb. You watch the clock – in forty-five minutes, it’s our turn! The minutes take hours and you pace the room and mentally violate the stage with all the things you’re gonna do up there when you get your chance.

There’s now about twelve people peppered throughout the room (most of them in the other bands) and your phone pings away with the last-minute excuses from people ‘unable to make it tonight, man, my leg’s fallen off’ or whatever. By now, you don’t care: hell, I’m gonna sonically smash this empty room to fucking bits, let me at it! And then, the moment you’ve been waiting for: ‘Thanks, London, we’ve been Satan’s Sphincter and you’ve been awesome’. We’re up.

This is the moment the entire day has been building up to. This is what we all came here to do. Thousands of hours of practice, countless callouses, broken strings, punched guitars, bleeding fingers, hand cramps and tears have brought you here – and by now, you don’t care that there’s hardly anyone watching, this is for you. You need this. As the drummer counts off the first song, a foggy cloud of bliss forms around you like loving armour and for the next twenty-five minutes you’re in Nirvana. (The spiritual kind, not the band.) In this moment, you are free. But it’s fucking hot under those club lights, and trying to contain your pent-up, animalistic release in that square foot of doom only adds to the aggression of it all. You’re up there together, a gang, representing your band and your songs with your comrades – you’re possessed and you’re fucking blasting. You’re allowed to do anything you want up there and people will think it’s awesome.

‘Normal society’ may not get it, but we do. It’s a drug. No. I’ve done drugs and it’s way better than that. Sex, perhaps? I guess it’s what the Quickening feels like in Highlander. Electrifying.

Exhausting. Sexual. Religious. It’s an intense, aggressive workout at the gym and a night out clubbing, condensed into twenty-five minutes. A dizzying cocktail of excitement, fear, ego and passion. Complete physical and mental dopamine bath. And then it’s over. Ringing with sweat, heart pounding, body rushing with endorphins, there’s no time to crash, you’ve got to get all your equipment off the stage within ten minutes so the next band can get on! Your set may be over but it’s still go, go, go. Before you can chat to anyone, grab a drink, or catch your breath, you’ve got to get your damn stuff out of the way – no one knows where, just get it moved

NOW! But it’s dark, there’re cables under foot, things to trip over and drunk people to navigate around while carrying an amp bigger than you – the whole thing is intoxicating – and shit, is that my bag I left up there?

Now you’ll have to wait until the end before you can leave – which of course you don’t do because you ALWAYS watch and support the other

bands.

You feel like a king. Like an undisputed champ. Like…well, like a rock star. And it feels good. Your body and soul needed that. Physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually revived. Carrying your collective high home with you, you sink a few beers, rescue your vehicle, do the load out, stop for late-night chips, big each other up, blast more cock rock and fight the inevitable post-gig system crash that always happens when there’s still two hours of driving to do, before finally getting home around 4am (if you don’t break down and they haven’t closed the roads). The alarm for your day job will go off in three hours but you can’t sleep. You played to twelve people, it cost you money and a day off work to do it and now you’ll be dead all day. Was it worth it?

I told you it was impossible to explain.

Excerpt taken from the book ‘Noise Damage : My Life as a Rock’n’Roll Underdog’ by James Kennedy. Published on October 18th through Eye Books. More information here: http://eye-books.com/books/noise-damage

James Kennedy’s new album ‘MAKE ANGER GREAT AGAIN’ came out on Sept 25th. He says its “Highly political, the album was written before lockdown and I perform all the instruments & produced it all at home.”