When political theorist Hannah Arendt observed Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann’s trial in 1963, she was struck by what she famously termed “the banality of evil”.

A fascination with this banality is also strongly evident throughout ITV’s 3-part drama Des. Des is the nickname of Dennis Nilsen (David Tennant), the real-life Scottish serial killer who between 1978 and 1983 murdered and dismembered an estimated 12 young men and boys.

Des begins when human remains are found to be blocking the drains at the complex of flats in which Nilsen resides in North London, and Detective Chief Inspector Peter Jay (Daniel Mays) is called in to investigate. Nilsen immediately confesses to “fifteen or sixteen” murders, claiming not to remember the exact number, which leads DCI Jay and his team to focus their investigation on the identification of victims. When it transpires that Nilsen is actually an ex-police officer, Jay’s superior officers press him to close the investigation and charge Nilsen with murder before all the victims have been identified, in order to avoid further bad press and spiralling costs for the force.

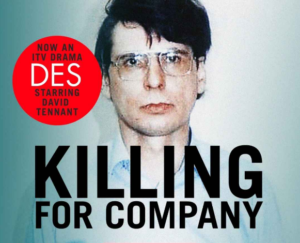

While on remand awaiting trial, Nilsen is contacted by author Brian Masters (Jason Watkins), who is intrigued by his case and asks Nilsen if he can write a biography of the killer. It is interesting to note that Des is based on this book, Killing for Company, which Masters would go on to write. At this point, the series threatens to walk the well-trodden path of the ‘sociopath confessional’ – murderers reveal all to objective third parties, who, along with the viewer, attempt to work out their motivations.

Famous examples include 1991 multiple Oscar winner The Silence of the Lambs and Netflix series Mindhunter (FBI criminal profilers), ITV’s 2011 two-part Fred and Rose West drama Appropriate Adult (a social worker), and multiple award-winning mafia sagaThe Sopranos (a Freudian psychoanalyst). It is a testament to Masters, though, that he never fully indulges Nilsen. Indeed, when Nilsen learns what the title of the book will be, the murderer suggests Nilsen would be more appropriate; however, Masters chides him: “But Dennis, this isn’t about you”. Masters is interested in how one human being can act so horrifically towards another human being, and as such his subject is humanity’s potential for extreme darkness, rather than the darkness in this single, outwardly boring, bespectacled civil servant.

Like Masters’ book, Des is not really about Nilsen himself. The skill and craftsmanship of David Tennant’s work here lies in his cold, understated performance, which allows the larger theme the space to develop around him.

Des is indeed about humanity’s potential for evil, and this is demonstrated with a focus on the victims and the impact on their families. Respect for them stands out not least in the performance of Mays, who is intense and engaging here as DCI Jays, as is Barry Ward as his detective colleague DI McCusker. The fact that Nilsen murdered young men and toyed with them after death yet cannot remember their names enrages the officers, and drives them to continue to seek to identify victims even after being ordered not to.

Very effective screen time is given to victims families, including a perfect turn by This Is England actress Chanel Cresswell as the distraught partner of Nilsen’s seventh victim. The very real grief of the families contrasts strikingly with the media portrayal of the victims at the time as drifters or homeless young men whose assumed homosexuality is portrayed as a risk factor for falling prey to a serial killer. This is another theme sensitively handled here – the audience watching in 2020 will cringe during a courtroom scene in part 3 as Nilsen’s defence barrister suggests the fact that one of the victims performs as a drag act on the weekends may have been a contributing factor to him falling prey to the killer.

The courtroom scenes of this concluding part, however, prove rather anticlimactic from a dramatic viewpoint. Nilsen observes his trial objectively, refusing to engage as to his motivations for his horrific crimes, leaving it up to the jury to answer the classic question of ‘mad or bad?’ This icy abdication of any responsibility, let along personal guilt or remorse, makes for an unsatisfying conclusion. It must be remembered, though, that Des is a docudrama based on very real events, and the unsettling lack of a clear conclusion for the viewer pales in comparison to how the victims’ families must still feel to this day.

The epilogue explains that Brian Masters continued to visit Nilsen in prison for 10 years; it also states that only eight of Nilsen’s victims were ever identified, suggesting that Masters’ decade of visits failed to illicit any further useful information. Throughout its 3 episodes, though, Des ensures that the victims get their stories told – their ordeals are laid bare. The final frame simply states the names of all eight identified victims – this is what the viewer must take away with them.