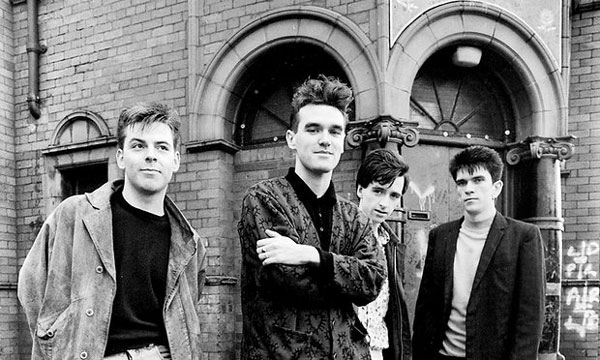

Morrissey cuts a more controversial figure than ever these days, now well past the point where anyone could feasibly even attempt to defend his offensive comments or totally unacceptable views. He has been reported as having said some truly shocking things in recent years, which none of us in our right minds would ever condone. To that end, for the sake of this article, I would like you to imagine, difficult as it may be, that after The Smiths split up there was nothing but an eerie silence, at least from one quarter of Manchester’s favourite sons.

Instead, let’s go back to a happier time – a simpler time when we found ourselves punching the air in delight at the lyrical genius of ‘Mozzer’, marvelling at the seemingly very intelligent, eloquent but shy, gangly individual who was brightening the lives of society’s outsiders, and, indeed, sometimes even playing a part in some of those kids’ minds that hey, maybe life isn’t so bad after all – I’m NOT ALONE.

It’s the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher, fresh from her ‘victory’ over the Argentinians in a needless self-made war in the Falklands, is at battle again, this time with the striking miners, destroying their livelihoods – their lives even – while society looks ever more bleak for the man on the street. Unemployment is at an all-time high, homelessness is rife, and British industry is crumbling by the minute. As a 13 year old schoolboy, like most people, my first encounter with The Smiths came with the entry of ‘This Charming Man‘ into the UK’s Top 40 (although ‘Hand In Glove‘ had been released a few months before and made less impact commercially). Oddly enough, I hated it on my first listen. I’d been used to the catchy fun ska-pop of Madness, or the theatrical pantomime of Adam and The Ants at this point, or the smooth Stateside AOR of Daryl Hall and John Oates, so the sound of a singer who seemed, at first, to be slightly off key was something extremely new to me and not something I felt was worth investigating further.

That thought was dispelled by the band’s electrifying performance on that Thursday’s Top Of The Pops. Here was the daffodil swirling, somehow shy yet uninhibited frontman I’d heard days before on the top 40 rundown, somehow giving off the impression that he was frighteningly intelligent too. Backing him was one Johnny Marr – a guitarist, looking the epitome of ‘cool’, in a black polo neck sweater with sleeves rolled up halfway – and a powerhouse rhythm section that complemented this intoxicating mix perfectly. But it was the next single, ‘What Difference Does It Make?‘ that well and truly won me over. That repetitive but sinister sounding riff and an opening lyric of “All men have secrets and here is mine, so let it be known…” – it all sounded so important, so alternative and, yes, so taboo.

To say the arrival of the self titled debut album was much anticipated is an understatement of mammoth proportions, and it didn’t disappoint. On first listen, I felt like the music was smacking me around the face and going “Listen! Listen to this PROPERLY!” and the combination of innovative, genius Marr motifs coupled with Morrissey’s sometimes humorous, often sordid sounding prose was an astonishing assault on the senses. I laughed, I winced, I recoiled in disbelief and thought “You can’t do that!” on several occasions: “A boy in the bush is worth two in the hand / I think I can help you get through your exams” growled Mozzer, somewhat controversially, on ‘Handsome Devil‘, one of many homoerotic references on the record (not least its sleeve), alongside the more humorous “I look at yours. You laugh at mine” on ‘Miserable Lie‘, which made me howl with laughter at the time and still makes me chuckle even now. Many of the lyrics here are deliberately sordid and depraved – a clear ploy to get the band noticed – yet they get away with it because the narrator in each of these songs seems to reject whatever sexual offers are thrown at him. Whatever you think of Morrissey, the individual, there’s not much likelihood of him ever being exposed as a Harvey Weinstein type, you can be pretty sure of that. I suppose you could arguably suggest that ‘Pretty Girls Make Graves‘ is a tad misogynistic with its indication that the woman in the song, who was after him purely for sex, has become fed up with her continually spurned advances and gone off to satisfy her carnal desires with another man (“a smile lights up her stupid face and well it would. I lost my faith in womanhood“), but it’s done in such a playful way that I don’t think you could really level such accusations with much conviction.

Of course, the most controversial moment arrives at the end of The Smiths, with ‘Suffer Little Children‘, an extremely macabre sounding number focusing on the utterly vile child murders carried out by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley on the Manchester moors in the mid-sixties. 36 years later, it remains an extremely uncomfortable listen, especially as the lyrics appear to be suggesting that Hindley only went along with these horrific crimes out of love for her partner. Morrissey himself even had to explain himself to the parents of the murdered children, and even struck up a friendship with the tragic Lesley Anne Downey’s mother, Ann West, after reassuring her of the true meaning of the song. Nevertheless, its haunting use of children’s voices laughing and sombre tones make it tough to take for many. I won’t lie – I tend to skip it when I play that album myself.

By the time the second album proper came out, Morrissey had established himself as something of a motormouth and a highly opinionated individual that was always good copy, so barely a week passed by without his face, or the band’s, peering out of the covers of NME, Melody Maker, Sounds et al. And of course, eager to capitalise on every moment, Rough Trade put out the ‘odds and sods’ compilation Hatful Of Hollow that comprised various Radio One sessions, B-sides and their recent singles (slightly different in some cases). The set is so effective that it very quickly became, by and large, accepted as an essential part of The Smiths‘ catalogue. And why wouldn’t it? It’s a stunning collection indeed. As an awkward, somewhat gangly, shy teenager myself with absolutely no idea how to talk to the opposite sex – the fear of rejection was strong in this one! – songs like ‘Girl Afraid‘ (“in the room downstairs, he sat and stared“), ‘Accept Yourself‘ (“Others conquered love – but I ran“) and ‘Please Please Please Let me Get What I Want‘ (self explanatory) were something of a godsend to me at the time. Here was someone who felt the same way as me, up in my darkened bedroom (it turns out he didn’t, but hey, I didn’t know that at the time, did I?) and I felt a whole lot less alone with The Smiths on my side. Hatful Of Hollow was a stunning record that bettered most bands’ best proper album! But even at this point, I was blissfully unaware of just what an impact they were going to have on my life.

In February 1985, the band released Meat Is Murder. For as long as I could remember, I’d been uncomfortable eating the flesh on my plate, knowing that an innocent being had suffered, violently and pointlessly, in order for it to get there. Until this point though, I’d always been led to believe that it was a crucial part of a human being’s diet, and that I’d be ill, or worse, history, without it. Here was a band saying what I’d always felt, deep down: that meat is, indeed, murder. The song had a similar impact on my elder brother, who announced one evening, in the wake of hearing it, that he no longer wanted to eat animal corpses. I followed suit almost immediately and remained vegetarian for around 30 years, eventually learning of the horrors of the dairy industry (initially through Erin Janus’s ‘Dairy Is Scary‘ video on YouTube) and transforming pretty much instantly to the vegan diet that I adhere to, to this day. But I digress. The fact is that this weird sounding song, full of distressed animal sounds and industrial farming noises, as well as the hypnotic lyric “This beautiful creature must die… a death for no reason, and death for no reason is murder,” was responsible for arguably the biggest – and best – decision I’ve ever made in my life.

The rest of Meat Is Murder is not that much more light-hearted either, but when you factor in Morrissey’s genius-like lyrics, sometimes once again consoling me by reflecting my own life (“I want the one I can’t have, and it’s driving me mad“) over the godlike Marr’s shimmering guitar arpeggios and jangly chord sequences, or the sombrely beautiful ‘Well I Wonder‘ (“well I wonder, do you see me when we pass? I half die“), it’s never depressing. Quite the opposite, in fact. Cathartic, even. And sometimes it makes us laugh like drains (“I’d like to drop my trousers to the queen. Every sensible child will know what this means” from ‘Nowhere Fast‘) or paints vivid pictures of a grim, violent Manchester on ‘Rusholme Ruffians‘ (“The last night of the fair – a boy is stabbed and his money is grabbed, and the air hangs heavy like a dulling wine“) and the overtly sexually aggressive masters at St.Mary’s Secondary School (“Mid-week on the playing fields, Sir thwacks you on the knees, knees you in the groin, elbow in the face, bruises bigger than dinner plates.”

Later in life, Mike Joyce would go on to bring a court case against the Morrissey/Marr partnership. While it’s questionable whether he was justified in doing so or not, listening to Meat is Murder, it’s the first time you really notice what the rhythm section is doing. It’s probably fair to say that without Joyce and bassist Andy Rourke, the records from this point on would have had a different sound altogether. You could feasibly even argue that the fearsome percussion defined tracks like the glorious ‘What She Said‘ and many of the tracks that would feature on the band’s best loved album, the following year’s piece de resistance The Queen is Dead.

Never is this more evident than on the startlingly triumphant title track, where Joyce and Rourke drive the song forward to its dramatic climax, every bit as important as Messrs Morrissey and Marr in this instance, on a song that you could easily argue epitomises what The Smiths were all about – rejection of the status quo, of the blind being led by the even blinder, but with a massive chunk of hilarious, self-depreciating satire. It contains the outrageously funny verse: “So I broke into the palace, with a sponge and a rusty spanner / She said “I know you and you cannot sing” / I said “That’s nothing, you should hear me play piano.” This was probably the point that the word ‘genius’ became inseparable from the band’s output, for me.

I remember playing The Queen Is Dead upon its release and being stunned into silence. One of those ‘jaw to the floor’ moments that don’t come along too often. Even the music hall folly of ‘Frankly Mr Shankly‘ – often cited as the most ‘throwaway’ track on the album by many and famously alleged to be an attack on Rough Trade’s head honcho Geoff Travis – chimed perfectly with many of us; a weary resignation from the dictatorial trials of working life, to find beauty in the simpler things: (“but sometimes I feel more fulfilled, making Christmas cards with the mentally ill.”)

But then there was the devastatingly gorgeous pull of tracks like ‘I Know It’s Over‘ and ‘Never Had No-One Ever‘ too, exemplifying the insufferable loneliness that most of have felt at some point or another (“…and as I crawl into an empty bed…oh well, enough said” or “I had a really bad dream. It lasted 20 years, 7 months and 27 days.”), the sombre self pity being dispelled at the end of side one by the bright and breezy ‘Cemetery Gates‘, feasibly the four piece’s most uplifting composition despite the implications of its title. If side A was exhilarating though, side B was nothing short of staggering…

Beginning with the brutal but amusing assault of ‘Bigmouth Strikes Again‘, The Queen Is Dead just got better and better with each subsequent listen from here on. ‘The Boy With The Thorn In His Side‘ – almost certainly the first hit song in more than a couple of decades to feature yodeling! – is conceivably the most divine three minutes ever committed to vinyl by anybody, ever. And that’s despite being on the same album as the stunning ‘There Is A Light That Never Goes Out‘, where Morrissey somehow makes the words “If a double decker bus crashes into us, to die by your side is such a heavenly way to die” sound like some of the most impossibly romantic prose ever penned. The atmosphere isn’t even spoiled by the cartoonish Carry On farce of the ridiculous ‘Vicar In A Tutu‘ or ‘Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others‘, which bookend it. If anything, those two light-hearted lyrical diversions only serve to heighten the impact of the more emotionally charged numbers. It remains an extravagantly incredible album and that’s why it’s still talked about now, nearly 35 years later, as a high watermark in musical history.

By the time the band’s fourth and final studio album was released, two more ‘compilation’ albums had been put out – The World Won’t Listen in the UK and Louder Than Bombs across the pond. Both had a similar track listing, though the latter was slightly more extensive with several earlier – previously released – tracks included too. Picks of the bunch were the charming single ‘Ask‘, the mildly provocative ‘Panic‘ (also a single, much to the chagrin of DJs everywhere, who had no desire to be hanged, actually!), the aborted single ‘You Just Haven’t Earned It Yet Baby‘ (another apparent dig at Travis) and the dark, moody but gorgeous ‘Asleep‘, that may or may not be the writer yearning for the end of life.

So what does someone whose music was roundly described as ‘depressing’ by the uneducated, the lazy and the terminally stupid, do next? Easy, he writes a song called ‘Girlfriend In A Coma‘ and releases it as a single, of course! As a teenager, I was incessantly telling the unbelievers that the band were anything BUT depressing. Thanks a bunch, Moz!

To be fair, it was an affecting song with a playful, cheery arrangement that made it hard to resist, despite its uncomfortable subject matter. It felt like a tongue in cheek needling of those who used the “depressing” cliche as a critique to describe the band, and that just made us fans love it more.

Famously, our dynamic duo have been regularly quoted as claiming their swansong, Strangeways, Here We Come as their crowning glory. It isn’t. But it is still, undeniably, superb. ‘A Rush And A Push And The Land Is Ours‘ is a quite splendid opener, featuring a hitherto rarely heard piano accompaniment to a song narrated, it seems, by “the ghost of Troubled Joe, hung by his pretty white neck some eighteen months ago.” It’s a fascinating idea, and Morrissey’s pantomime gurgling makes it doubly so. Then we’re hit with ‘I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish‘ which, controversially, on the surface, seems to allude to some kind of sexual assault. But that’s the beauty of The Smiths’ music – there’s often a deeper meaning, and it may not be what you first thought. Further investigation perhaps suggests that the character in the song is gay, and having mistakenly misread the situation, made advances at someone who is not. Furthermore, it could also be about the Morrissey-Marr partnership itself, with lines like ‘I grabbed you by the guilded beams, Uh, that’s what tradition means / And now eighteen months’ hard labour seems… fair enough!” as though the frontman has put pressure on his faithful guitarist to come up with the goods and it all turned out nice again in the end. Whatever, only the author knows the absolute truth.

The impressive orchestration on ‘Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me‘ is breathtaking, the thrill of ‘Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before‘ has never diminished, and you can’t help nodding in agreement with ‘Paint A Vulgar Picture‘ in its withering – or perhaps scathing – criticism of the music world’s cynical reappraisal of an artist’s merit after their death: “Re-issue! Re-package! Re-package! / Re-evaluate the songs / Double-pack with a photograph / Extra track, and a tacky badge.” But for all Strangeways‘ resplendent, string-laden grandeur, I would suggest that the simplest arrangement on it, the alluringly pretty ‘I Won’t Share You’, is the most captivating moment on it. Once again, the meaning of the song is ambiguous, but that doesn’t stop it being one of the greatest, most arrestingly beautiful, album closers of all time.

In truth, I could probably make a case for practically ANY of The Smiths’ songs being their best (well, maybe not their version of ‘Golden Lights‘ but to be quite honest, I even think that’s a lot better than it’s ever been given credit for). They were always there for me on my darkest days as a teenager, lifting my spirits at times where I felt that was impossible. I haven’t yet even mentioned the astonishing ‘How Soon Is Now?‘ (a completely relatable song for me back then, as a painfully shy young man, especially with lines such as “There’s a club if you’d like to go. You could meet somebody who really loves you / So you go and you stand on your own, and you leave on your own, and you go home, and you cry and you want to die.” – I mean, I was never quite THAT extreme about it, but I got where he was coming from!) or the electrifying ‘Shakespeare’s Sister‘, but let’s face it, I don’t need to, do I? Because if you’ve got this far, you’re obviously a huge fan too. Why would you be reading otherwise? But we cannot cling to the old days anymore, so join me as I lift a glass in celebrating The Smiths – the best British band of all time!

Main image by Stephen Wright.