‘I think I’m a-come to a point where I’m not gonna be wanting to travel that much,’ says Lonnie Holley as he places a delicate bonsai-scale branch next to a coiled length of electrical cable and takes careful aim with his camera phone. ‘But I think I already done enough music. I wasn’t interested in going out trying to be no rock star. I had a message to deliver, and my music is about the message that humans get out of my music. What can I say?’ Quietly, conversationally, he starts singing to me, ‘I wanna be ready / I wanna be ready / Walk in Jerusalem just like John / I wanna be ready / I wanna be ready / Walk in Jerusalem just like Jo-Anne. You understand what I’m saying? It doesn’t have to John, it could be Jo-Anne. It could be anybody, but I want to be ready in case a storm comes, a tornado, a twister come. I want to be prepared to be able to handle that.’

I nod earnestly. ‘Readiness,’ I say. ‘Yeah’.

‘Most people can’t handle that,’ continues Lonnie. ‘They can’t handle rising water. They’re not equipped. They’re not ready.’

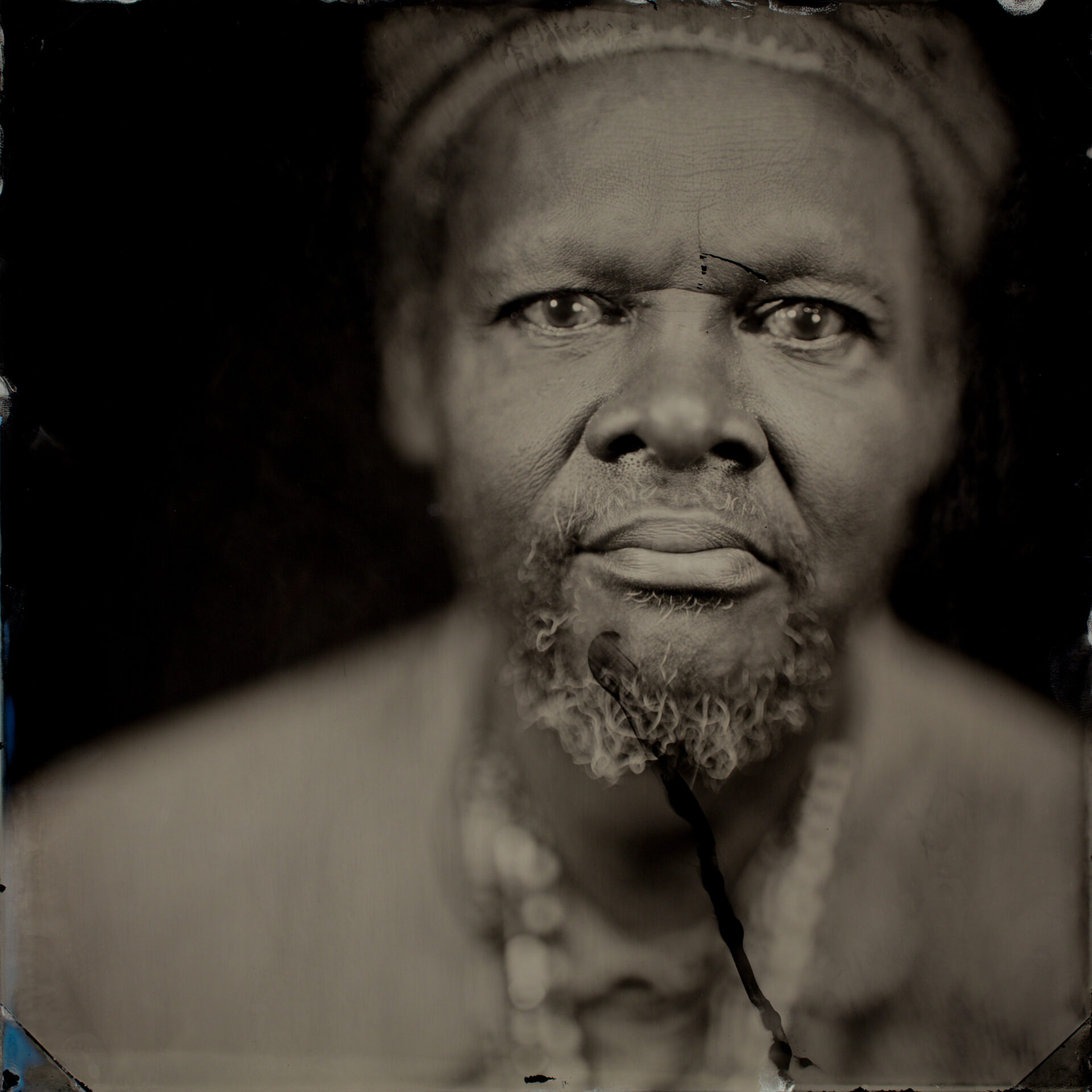

I’m in Bristol, where Lonnie Holley has come to spend the weekend of his seventieth birthday at The Cube Cinema, a run-down, ramshackle community space in Stokes Croft.

Yesterday he showed us some movies, the documentary The Man is the Music and the films that he made to go with his songs ‘I woke up in a Fucked Up America’ and ‘I Snuck off a Slave Ship’, followed by a question and answer session with his manager Matt Arnett. Tonight we’re going to get one of his improvised musical performances, a heady distillation of traditional blues and cosmic jazz.

Better known as an artist than as a musician, he’s in the UK because his work has been included in an exhibition at Turner Contemporary in Margate, We Will Walk – Art and Resistance in the American South (until 3 May 2020). The exhibition pulls together paintings, assemblages, quilts and other artefacts by more than twenty African American artists from Alabama and nearby. Much of the work is engaged with a common background in civil rights protest and shares a set of concerns to do with reuse and remaking of found materials.

In The Man is The Music, he explains that he began singing as soon as he could get the sounds out. The film follows him as he goes about his work – in his studio, in the street, in the creeks and edge-lands of his home town of Birmingham, Alabama. Here and there a bit of detritus catches his eye and gets fashioned into an art-work, all the time singing as he goes. He sees himself as an investigator, he says in the film, collecting junk and garbage which tells a story. We threw away too much, he says at one point, but among the things we’ve discarded, he has found hope, hope which is waiting for you to rework it.

Lonnie’s life story has been well documented elsewhere, most thoroughly by Rebecca Bengal for The Guardian. It’s hard even to pick out the main points among all the twists and turns, but briefly, Lonnie was the seventh of twenty-seven children. He got separated from his family, traded for a bottle of whiskey, was hit by a car and wound up in a coma, and subsequently was incarcerated in the notorious Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children, in reality little more than a forced labour camp, where he was made to pick cotton with the other children. He describes his art and music as a way of living with and controlling these traumatic memories and as a way of helping others live through their own traumas.

Before each show, he is introduced by his manager, Matt Arnett, the son of William Arnett, the art collector and founder of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, who has acted as patron to Lonnie and many of the other artists included in the Turner Contemporary show. Matt tells the story of how Lonnie discovered the power of art in 1979 after the death of his niece and nephew in a house fire. Following the tragedy, his sister had slipped into a deep depression, compounded by the fact that she had no money for gravestones for the two children. So Lonnie carved her some, from the soft, friable bits of concrete used as moulds and discarded by the local steelworks. Her reaction transformed Lonnie’s understanding of what his role on mothership Earth could be. Today his work is on display in museums up and down America, including the Smithsonian and the Met. Margate is a rare chance for a British audience to see his sculptures and the work of his contemporaries, artists like Thornton Dial and the Gee’s Bend Quilters among others.

Talking about the film that accompanies Lonnie’s best known song, ‘I Woke Up in a Fucked Up America‘, Matt dismisses the notion that it’s anything specific to Donald Trump’s election. It might have come out at around that time, he says, but Lonnie has been waking up in a fucked up America all his life and so have his entire family for generations – his mother, father, aunts, uncles, grandparents, great-grandparents. Waking up in a fucked up America is nothing new for them.

I’ve come for the music, so I’m a bit horrified that Lonnie keeps telling me that he didn’t want to be no rock star, but the fact is that for years no one thought of him as a musician at all. He would sing alone as he made his art, sometimes accompanying himself on an ancient, thrift-store Casio that he had taken to pieces and somehow got working again. Then, in his sixties, word got around via home-made recordings and he was invited on tour with the likes of Bill Callahan, Deerhunter and Bon Iver. 2018’s album MITH on Jagjaguwar stands as one of the best LPs I can think of from the last ten years and my attitude can more or less be summed up as MORE PLEASE LONNIE. I am completely, utterly enthralled when he starts singing just for me.

As we speak Bristol is getting a buffeting from Storm Dennis, and the conversation turns repeatedly to the environment. I ask him how climate change has affected him in the United States. The answer is typically Lonnie – straight into the big picture.

‘Climate change is all about all over the world,’ he says. ‘My art has been talking about that for years and years and years. What’s in the water flow or the acid rain and all of these other things that I’m processing in works of art, or how I took the debris that was up and down the creek. I could show you how some things can rot a lot faster than other things and some things won’t rot until years later.’ I nod and mention the tiny bits of micro-plastic that get into the food chain.

‘Man, nobody goin’ even understand about the particle-ness of that. That’s tiny, tiny, tiny, tiny all the way down to a grain of sand tiny-ness, those little bitty particles of plastic, you wouldn’t even believe it how all this stuff can get clogged up in a whale or get clogged up and stop the bowel movements of a lotta creatures.’

‘You can see that stuff hanging on that tree there?’ He gestures to the window. Outside, on the bare branches of the tree in the courtyard, there’s remnants of what looks like bunting. ‘When that gets in the waterway it gonna float on down the water, and it’s gonna get tangled up in this root right here, and then before you know it, it gonna get burned up. Some things if you get it down into what you call the drainage or a sewer, it’s gonna stop the whole sewer up. And once that stops the sewer up, whatever, the seedlings that’s coming behind that – once that seed hits that, it’s going to start growing and then any cracks that’s in the ground between those pipes and the surface of the earth those little, bitty roots crack those.’

‘I think if you go to Margate you gonna see Him and Her Hold the Roots. If you look at the tininess of the roots, not only am I talking about ancestry with information about DNA and whoever we are and from wherever we came, but we are also talking about damage that can be caused by some massive strength in that oak tree. The oak root, man, that’s a strong root. Once that root start growing it’s gonna burst everything. You ever been riding your bike or just running along the sidewalk and see a tree breaking up from the ground?’

The tree always wins, I tell him. He nods, ‘the tree wins every time.’

Lonnie Holley, in many ways, is that tree. We talk about how, in 1997, the city authorities in Birmingham tore down the three-acre patch of land he called his Environment. He lived and displayed his work there for years until local government swept it away to make more space for the airport. It must have been heartbreaking, I say, feeling rather useless.

‘Not only heartbreaking. It almost killed me. Because it was something that I had to try to move real quick.’

’It was bad enough for me moving house recently,’ I continue, fatuously, since there’s nothing in my frame of reference to compare, ‘and I have nothing.’

‘I got ill. It was so much that was going on, I didn’t have the funds to move, I was being forced to move, I had five children, my wife was in prison at the time, I was trying to take care of my children to keep them in school every day, feed them, give them their nourishment, make sure that they have their clothes and everything. And being a father or big brother or son to my mother, a grandson to my grandmother, I was doing all of these things, and it was like I was a big old yo-yo. I didn’t mind – the more I have to do the better I feel about doing, but it was just that it was so much stress and the way that they did it… it really, really was art abuse. If you haven’t heard about art abuse then I am an example of a great amount of art that was abused, tooken advantage of, stolen, and otherwise just buried. But it didn’t stop me.’

If that sounds like an overstatement, don’t forget that when this was going on, Lonnie already had his work on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For a city to lose a space like Lonnie Holley’s Environment would be like the Ayuntamiento de Barcelona tearing down Parc Guell to build student flats. And if you think that Lonnie Holley ain’t no Antoni Gaudi, well then, Birmingham, Alabama isn’t exactly Barcelona either.

I ask him where he shows his work nowadays and he produces his phone and we scroll through his Instagram feed. I smile when I see that he’s followed by Julia Holter, Kathryn Joseph and Kamasi Washington. Of course, I think to myself, yes. Those three are going to be very much on board with every aspect of this. He calls it computer art, collages of photos that he’s been making during down-time on the tour. In London, he made bicycles ridden by bags of trash, and last night he went around The Cube photographing their lights and arranging them around Benin masks from Africa. His mother is Yoruba, he says, from Nigeria, like the Benin.

‘People,’ he says, ‘they always try to put me in a category. But look there. Look at that. That’s uptown London. All stuff that was on the side of the road, so what I did was I took the picture and then I manipulated each one of the little bitty cut-outs and I put em all on the bicycles – can you dig where I’m coming from?’

‘Yeah,’ I say, admiring the trash-bikes, ‘I love the way you work with rubbish and things that people just discard and don’t want to look closely at.’

‘Everything,’ he replies nodding, ‘Everything. I’m trying to show that we can’t put no gravestones on the landfill. We can’t put no gravestones on landfill.’ It’s a hell of an image, one that bears the awful weight of the epiphany that made an artist of him.

He talks to me about the women in his family, how they formed his view of art. ‘My grand-momma taught me a lot because she was the one that dug graves. And how the waste, and materials and stuff that was thrown away, they burned up as much as they could, but otherwise it’s thrown into this big pit of landfill debris. And then it’s ran over by the big bulldozers or whatever, constantly, all day long, and packed. And then with momma, the inspiration that I got from her was choices of materials that we could still use. Because of momma having twenty-seven children out of thirty-two pregnancies, momma was always looking at materials, ripping down materials, making quilts and making blankets, making whatever else, making diapers.’

‘Because everything was precious, right?’

‘Yeah, just like you say. I love you for that. Making stuff out of everything because it was precious. You understand what I’m saying? So it’s the same way now, but we don’t see on what scale. To some people, just another day of life is so precious, because last month a hurricane came through and destroyed their ordinary lifestyle. So my thing as an artist, I try to make it be a lesson that can be passed on. Because just like I said, tomorrow I’ll be seventy years old and with me being seventy years old, I think if don’t do anything else after I go onstage and do whatever I gotta do tonight, I wanna say live the very best that you can for the day. And know that. Because tomorrow is not promised to you.’

He talks me through the tree branch and the cable he’s brought along, mulling over what he’s going to do with some local school kids who are coming along on Monday to make art with him. This community aspect of his work is clearly important to him, particularly as he had very little formal schooling himself. You can hear it in almost everything he says – a very smart, quick brain, beaten down by the trauma of his childhood, left to grapple intuitively and alone with everything that came into its path. Even in the middle of an interview, his mind is restless and can’t keep still, freed by art, seeing art everywhere, making connection upon connection.

‘I’m seeing ideas that are so beautiful. Look outside the window, you see the ‘Caution’? The yellow thing for when the floor is wet, you see?’ I look and just outside there’s a yellow, plastic warning sign stood on a set of steps visible from the barred window. ‘It’s a sign, but it also is a warning. So now I’m seeing it 3D, but what? The bars is on us now? It’s like we’re the prisoners.’ This might sound a bit silly because right now, me and Lonnie aren’t prisoners, we could walk out the door anytime we want. But he’s right, I think, there are bars on the windows. This is totally what it looks like. ‘Prisoners against the elements,’ he continues, composing the image for me. ‘Caution, elements is on the outside! What’s going on with the elements, with the storm, in certain islands now when the storms hit, they’re category three, to four, to five, and that’s totally destructive, tearing up everything.’

‘Sometime we ask the question, and humans may not understand, I cry to pity for them, but Momma said, don’t be stupid. I cry to know that peoples are dying because there are chemicals in the creatures and then those creatures is being eaten and then we catch the disease that’s in the creatures. And then, therefore, we get sick. Toxics. China is an example for us to straighten up and try to understand what some of our conditions is. Again, very scary. Because chemicals is mostly in everything we use in our farms, in our agriculture, mostly everything one way or the other. Even if you say, we gave you free-range chickens, it’s an organic chicken – no, it’s not free-range chicken, it’s not organic – if the rain picked up the toxic dew, added it to the rain and it drops back on, what did you get?’

‘There’s no boundary?’ I suggest.

‘There ain’t no boundaries.’

‘People imagine that there are,’ I say, ‘that you can take a bit of stuff, throw it away and it’s gone, but that’s not true.’

‘Your imagination can’t play that game. No imagination can’t play that game.’

He sounds genuinely a bit vexed by this thought. Rightly so – playing the interview back days later I hear myself use the word ‘imagine’ and kick myself. Imagination is probably the only quality that will get us out of the mess we’re discussing and Lonnie of all people, if he knows anything at all, knows this. If we used our imaginations more – he interrupts me.

‘All I’m trying to do is say what I have learned,’ says Lonnie. ‘Not what I think. I mean, think about me being an artist since 1979. For years I checked out more materials and the identification of materials and the materials’ value than pretty much any other artist than I know on Earth. But I don’t wanna boast about that because I’m not trying to act like I’m better than everybody else. I want everybody else to get better than me and learn from what I’ve been an example of. I am a geographic artist.’

I ask him to expand on this.

‘From every mountain top. To every valley low. From every drip of water to the way the water flow. That’s geographics. From the highest to the lowest. To the depths of the ocean floor. It all meets and all be one. Part of the mothership. Why we in search of another ship? While we in search of another ship, we’re draining this ship of all kinds of fluids, that was necessary for this ship to just keep with this internal burning.’

I try to pester him about space travel. The idea comes up a lot in his music, and he’s often been compared to Sun Ra, another famous son of Birmingham, Alabama, although Lonnie has always denied any knowledge of this kindred spirit’s work before it was pointed out to him. He dismisses the notion pretty quickly, telling me we need to think more about the planet we’re on.

I remind him of a question from the audience last night. Lonnie’s left hand is covered in rings and bracelets, while his right hand is bare. I’d noticed this too and assumed that there was some philosophical or symbolic reason for it. But it’s actually entirely practical.

‘In effect, it’s really so,’ he picks up the cable to show me. ‘Like when I’m gripping, so now the ring is like a cushion between the material and my finger. So I don’t get no calluses on my hand. And with the things that I wear up my sleeve when I’m holding materials like this right here, I’m cutting here and nine times out of ten you can still feel that wire. Feel it, now try to bend it. That’s what I’m talking about.’

‘You work that all day you’re going to get calluses,’ I say.

‘Calluses plus when you’re cutting, like this right here, it may slip and I don’t cut myself. So it’s always protective. And also its a kind of show, I like beautiful things, I’m not so much into gold. I got a couple of little pieces of gold on, but I’m not into heavy gold.’

‘I think Matt said a couple of things about how when people say you’re a visionary, is that a misreading? Is there something a lot more practical about everything you’re doing? How does it seem to you?’

‘What I’m doing is for the times. If you see all the wind blowing out there right now, all the little particles that you can’t see are blowing with that wind. We don’t see it, but it’s in the air and it becomes caught up in the raindrops. So I think about what we have to do for the future and how we have to orchestrate certain materials. See, if I am working for the environment, I’m an environmental person. Also, if I’m speaking on the behalf of the environment, and it just so happened that I may say something about civil rights, then civil rights boil down to the point of having the right just to have an education where I can better myself to become of better service to life while I live.’

‘It’s almost like Gee’s Bend Quilters say, Give Me My Flowers While I Yet Live. Don’t bring a bunch of artificial flowers and think that’s going to soothe the spirit because it’s not. There is nothing happening with artificial flowers. For one thing, there is no fragrance there, and also by now, you have stripped the opportunity for seeds or any other kind of growth as an example of something that can still be planted. So we move toward that as we grew into being the humans that we were.’

The mention of civil rights gets us onto politics. He’s disgusted by the meltdown at the Democratic caucus in Iowa. ‘It was already fore-played,’ he says in a dismissive tone, ‘It was already put in play. They knew what they was doing. And if you knew what you was doing, then it became tricks to those that wasn’t smart enough.’ He talks approvingly about how one of his fellow artists in We Will Walk uses fake jewellery in her work. ‘What we think is gold is just processed material to look like it’s gold or diamonds. We get fooled and tricked, and sometimes we get fooled and tricked all the way to death. And these are the types of things that have came up in the type of artists that I’m talking about.’

‘But you want to play on fake media, but all the time you was going to do something so fake that it became the big bada-bang of fake. And that hit the nation all at one time. Pow! We didn’t see this coming, that Cold Titty Momma – I call it Cold Titty Momma, C.T.M., Computer Technology Management – was going to be managing. Was it going to be managing All Render Truth from an Internal Self?’ Lonnie counts the words off on his fingers for emphasis as he says them. ‘All Render Truth, A. R. T. I. S. Was it going to be managing the arts of politics? I swear to tell the truth and nothing else but the truth so help me, so help you, so help y’all, for all the generations yet to come.’

Cold Titty Momma comes up a few times over the weekend. This image of a culture suckling on a digital nipple seems a particularly bleak take on our dependence on technology and its corruptions. It provokes a knowing laugh when he explains it to the audience at his shows. Yet, all of us, even Lonnie with his enthusiasm for Instagram, are connected. As we’ve already said – no boundaries. No boundaries at all anymore. He tells me about one of his earlier works, a sculpture called ‘In the Grip of Power‘ made from a polling booth and which commemorates the struggle of those who won the vote for African Americans in the US, while also commenting on more recent efforts to disenfranchise America’s black and working class communities. The way that an act as fundamental as voting is changing, going from something as tangible as a mark on a slip of paper, to the ineffabilities of computer analysis horrifies him.

The interview wraps up with a lengthy investigation of the steel cafetière that the staff at The Cube brought me coffee in. Lonnie’s never seen one like this before and is keen to see how it works, while also using it to illustrate some thoughts he’s been having lately about volcanoes and how they could be harnessed for the betterment of humanity.

I’m conscious that I’ve taken up a lot of his time and that we’ve said very little about music. Is he really going to stop touring? He runs me through a couple of his health problems, but the fact is that he’s going to be seventy tomorrow. He survived so far against the odds, but it’s not getting easier.

‘I’m having to move constantly. Sometime I don’t feel like it, but again, I’m doing the very best that I can as an African-American artist. There’s still music. My children say, daddy, why did you choose this? You’re not a rock star. I know I’m not a rock star but I choose to do as much as I can to help the rock stars have a stage to be able to rock and roll and do that jazz, blues, classical music, whatever else that they wanna do. You gonna stay tonight and hear this?’

I tell him that I am and he asks me to remind him who I’m writing for. I tell him it’s for God is in the TV. I can see his mind go to work on this straight away. ‘God… is in the… TV? God is in the TV, huh? I like that. Even in the TV.’

Before the gig, I head out for a walk around Stokes Croft to clear my mind and take in some of the encounter I’ve just had. The wind and the rain seem to have passed by, but only the most intrepid or desperate denizens of Bristol are out and about. A couple of figures have set a fire with some cardboard boxes and other garbage on a patch of waste ground over the road from Hamilton House. Caustic smoke drifts down the empty street. Discarded men and women with fresh-looking sores on their faces mill about the corners looking for whatever it is they’re looking for. England is a depressing place these days. Meeting Lonnie Holley – and I’ve been fishing for this interview for a while now – approaches how I imagine it would be to meet someone like William Blake, someone whose frame of reference might occasionally be a bit far out, even a bit crazy, and whose life might feel separate from mine by a chasm of experience and genius that neither of us could hope to grasp. And yet it doesn’t seem to matter. The man talks my language.

Back at the theatre, I’m lucky enough to sit in for the soundcheck. It’s as I’ve heard it described. Lonnie plays a few bars of something and comes up with a starting point, a line or two that Matt Arnett writes down for him. Then another and another, and that’s the setlist done, and Lonnie goes back to his ruminations, gathering his energy for his audience.

At the show, Lonnie pays tribute to his hosts at The Cube. Describes how he identifies with its history and ambience. He shows us his lifetime membership card. ‘It’s beautiful,’ he says, ‘to know what a little card can do for you.’ He sings about his childhood, being passed from hand-to-hand in Alabama. About violence, about picking cotton. ‘I remember them telling me,’ he sings, ‘they done told us we not having no mistakes.’ His old Casio sounds like water flowing underground. Otherworldly, cosmic reverberations flow from it. It’s a treat to see him without a band tonight.

He tells us not to be distracted, that he’s here to tell us not to be distracted from the greatest you could ever be. He tells us about Cold Titty Momma – those computers will not cry for you, he says. Those computers won’t dig the graves. In one song he even manages to squeeze in a plug for the show in Margate. He hopes we’ll go and see it. As the song closes he pushes his glasses up onto his forehead and wipes the tears from each eye. He talks about his community work here and in Margate. How he’s teaching the kids to tie the rope for hope. He’s teared up, but he’s happy. ‘Beats singing happy birthday to myself all day,’ he says. There is applause from a room genuinely full of love.

Then he sings a song just for me. He’s on a rocket ship, strapped down in his seat. Sent to space in a probe that gets lost, and he goes nearly mad thinking about aliens, and about what he might find if we keep going further and further. The ship loses all power, the planet is wobbling on its axis, deserts burning, heat filling the air. He looks up and sings, ‘We must turn around.’

Thumbs up to Mother Universe, Lonnie. And happy birthday.

We Will Walk – Art and Reisistance in the American South is on at Turner Contemporary in Margate until 3 May 2020. MITH by Lonnie Holley is out now on Jajaguwar.