Hayward, California rapper Spice 1 has always been supported by street culture. In 1983, when he went by Fresh Rock, his tag and breakdance name, Spice 1 says, “I would go to Pier 39 in San Francisco, breakdance, and actually get money doing that.”

A few years later, Spice 1 was discovered by the Bay Area legend Too $hort. Randy Austin, $hort’s manager at the time, was informed by his niece that her high school classmate Spice 1 was a talented rapper prompting the $hort Dog to call Spice 1 and invite him to his studio. Spice 1 recalls that once his friends on the block saw him going to the studio with Too $hort, they told him, “You may make it. Get out of here.”

After recording his first single cleverly titled “187 Proof” after California Penal Code 187(a) for murder and the measure of alcohol content in alcoholic beverages (proof), the same guys on Forsella Circle who pushed Spice 1 into the studio, bumped the song that came to Spice 1 in a dream about anthropomorphized alcoholic drinks in a noir narrative, and created enough neighborhood buzz around the record for it to cross over into mainstream success.

While the shaky streets of the Bay Area ironically provided Spice 1 with a platform to rap—pun intended—his father provided him with a foundation for strong communication skills. Spice 1’s father was a poet involved in the Black Panther Party, a revolutionary political party founded in Oakland, California in 1966 to “police” the Oakland Police Department’s treatment of the black community it purported to serve. Through the disobedient and outspoken nature of the B.P.P., along with the government’s attempt to censor it, Spice 1 experienced language transcend racial barriers, which influenced Spice 1’s songwriting process. On songwriting, Spice 1 explains,

“There are a lot of things out here and you can’t just look past them. You have to teach the people and they have to learn what is going on. I would be wrong for not telling them what is going on. That’s how I feel and that’s my job to tell people what’s happening, whether they like it or not.”

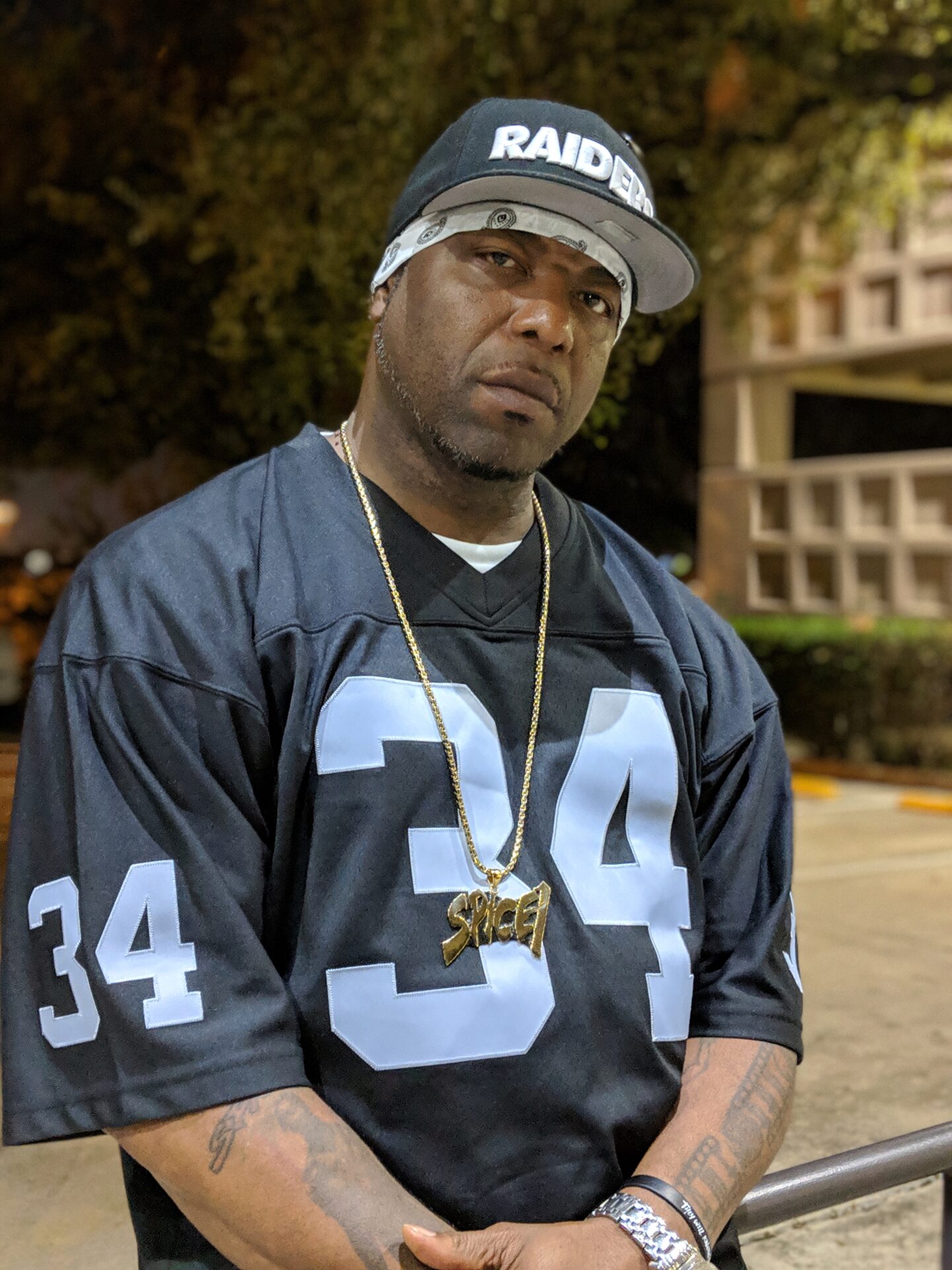

This past summer I had the opportunity to sit down and speak with Spice 1 at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY in the Television and Video Production Studio, while he was in New York City promoting his new album titled Platinum OG. Spice 1 was accompanied by Ryan Elder of Elder Entertainment, who is responsible for the production of Platinum OG, videographer Dr. Teeth, and rap artist Nawfside Outlaw.

Photo by Kayle Hope

Spice 1 and I discussed his unique background and connection with Hip Hop and how that affected his evolution as an artist. He also told me about his relationship with Houston and how he first met D.J. Screw. And, Spice 1 shared his feeling on featuring verses from deceased rappers on his new project, Platinum OG.

Tell me about yourself.

I come from a small city called Hayward, in California, 15 minutes away from Oakland, where we see a lot of stuff go down. My dad was into the Black Panther Movement. My dad wrote a lot of poetry and was a motivational speaker so poetry and speaking are my specialty. I’ve been known to get a lot of cats fired up when I rap.

How did you get your break?

It was the song, “187 Proof.” I dreamt the song up. First, I prayed to be a rap artist. I had a few drinks and went to sleep. And, I dreamt that I was a rap star; in my dream I am walking down the street and there was this dude playing some music real loud. I walked up on him and said, “What’s that you are playing?” And he said, “I’m playing Spice 1 and this is the new shit right now.” Something told me to stick my head in his car to see what song made me famous. I got a few bars of what I was saying and I heard the beat and the melody. I heard myself say, “E had the nine and J had the A.K.” Then I woke up. I am like, “Who the hell is E and who the hell is J?” and I started thinking; E and Jack, that’s alcohol. What if they sold dope on Hennessey street? Then I went with it and started writing the whole song about alcohol and making the alcohol sound like people and I called the song “187 Proof”. Once I got the song down I went and recorded it and I passed out a few tapes on my block on Forsella Circle and everybody started playing the hell out of that song. That’s what did it. The song I pulled out of my dream is the reason I am sitting here talking to you now.

Throughout your prolific career, you’ve been politically outspoken, releasing albums such as, AmeriKKKa’s Nightmare and 1990-Sick. You’ve been featured on America is Dying Slowly, which is a compilation album to raise awareness about the AIDS epidemic. You are known for powerful lines like, “from across the seas comes cocaine, but you’ve never seen a black man fly a plane.” Tell me about your heavy social commentary.

My dad and my uncles were Black Panthers. I would go to the Uhuru house on East 14th in East Oakland, after I got my hair cut and watch my dad speak and say things that made a lot of sense. We had Panther pamphlets at the house and the F.B.I. came to the house and asked my mom where we were sending the pamphlets. That sparked something in me; my dad and my uncles must be saying something right because they were trying to stop us from saying this stuff.

By the time I got to the age of 18 or 19, I got harassed by the police a few times and I was tired of that. I had a few friends do some serious time over some small stuff and I was kind of sick of it. Back in the day, in Hayward when we got pulled over, the whole neighborhood would come outside and make sure the police were doing their job right.

With music we had Public Enemy, B.D.P., and all these motivational speaking rap groups that were from New York and I wanted to be part of that. I knew that when you say something that means something, it lasts forever and that was cool to know my music would be here while I was lying in a grave somewhere.

Why is it so important for you to be heard?

There is a lot wrong in the industry and in the world right now. People don’t think straight and they are not thinking rationally. There is a lot that drives me to keep it as real as possible. Because without real you don’t have shit.

What do you mean?

Without real you don’t have anything. When you talk about something that’s real you have foundation and longevity because people remember that shit; they remember “From across the seas comes cocaine but you never seen no black man flying no plane.” When you say stuff like that it lasts and people respect you for it whether they are on your side or not. You want people to think you are intelligent no matter where you come from. I come from the streets and I’m as hood as possible, yet I speak my words correctly.

On your song “Ghetto Star,” from your album Thug Candy you mention Houston and DJ Screw. What does Houston and D.J. Screw mean to you?

My cousins, aunties, and mom were all in Houston. Well, my mom was in Bryan, but everybody else was in Houston. And, I was out there chilling and my cousin was like “There’s this dude named D.J. Screw and he makes this music and he slows it down and I think he got some of your songs.” I said, “For real? Let’s go over there.” And so, we went over to Screw’s house.

Screw was sitting up there choppin’ up music and stuff. And, I am like, “What is that shit over there you are pouring?” He was like, “Yo man, we call it syrup. We pour it in soda and put the jolly rancher in there, and we let it get real cold and then we drink it.” I was like, “Oh shit…” (Laughs). So we were in there trying to record and we ended up doing a few songs and recording a lot. I didn’t know it was going to (Spice 1 makes explosion sound). The fans were like, “Oh you got a song with D.J. Screw? Ya’ll was kicking it?” I was like, “Yeah, that’s my homie.” After that, we were friends up to the time he died. I became friends with all his friends; the whole Screwed Up Click are my friends.

What year did you do that “Freestyle” on The Meadows Screw Tape?

1992, 1991, maybe even 1990. I was telling him to turn on the beats and he said, “I am going to slow down ‘East Bay Gangster’ and just rap.”

Besides recording with Screw, did ya’ll do anything else?

We would go out to the clubs and get a few females and take them back to the Screw shop, kick it, and drink and chill. He was a real cool cat. We never argued or nothing. We were always just cool.

With respect to your new album titled, Platinum O.G., how does it feel to have several deceased artists featured on this project?

It is really inspiring because they are immortal. I can’t physically shake their hands and say, “What’s up homie?” and give them a hug, but listening to their music makes it feel like that. It brings back memories every time I hear their voices. Big Syke is on their like four or five times and it is just so cool to hear my homie’s voice rapping behind the beat that I am on. You know, every time something happened with ‘Pac, I’d call Big Syke and be like, “Man, did you see that shit?” and then when he passed, I’d call Mopreme, ‘Pac’s brother. Shot out to Mopreme. What’s up fool? Thug Life forever, man. You already know. We throwing up the M.O.B right now; money over bullshit.

Follow Spice 1 on Instagram at @therealspiceone

Main photo Courtesy of Elder Entertainment