Later, as he sat on his balcony eating the dog*, Colin Bond wondered what the devil he was going to write about Zone Rouge, the new album by Right Hand Left Hand. He was, in his own opinion, if not in point of fact, slightly late with the piece. Having had a couple of months to put together his thoughts, he had quite uncharacteristically left it until a few days before the release date to begin committing these thoughts to paper, and, as he usually found when given too long to ruminate upon a particular topic, had a wealth of things to say but no obvious way to begin saying them. The fact that his editor, Bill Cummings, was also handling PR for the band was an added incentive for procrastination. Not that Cummings would have sought to influence a contributor’s opinion one way or the other. But, as he surveyed the bedraggled wreckage of the over-priced apartment he had purchased following his divorce, Bond unaccountably found himself entertaining the urge to please, a fatal weakness in any critic.

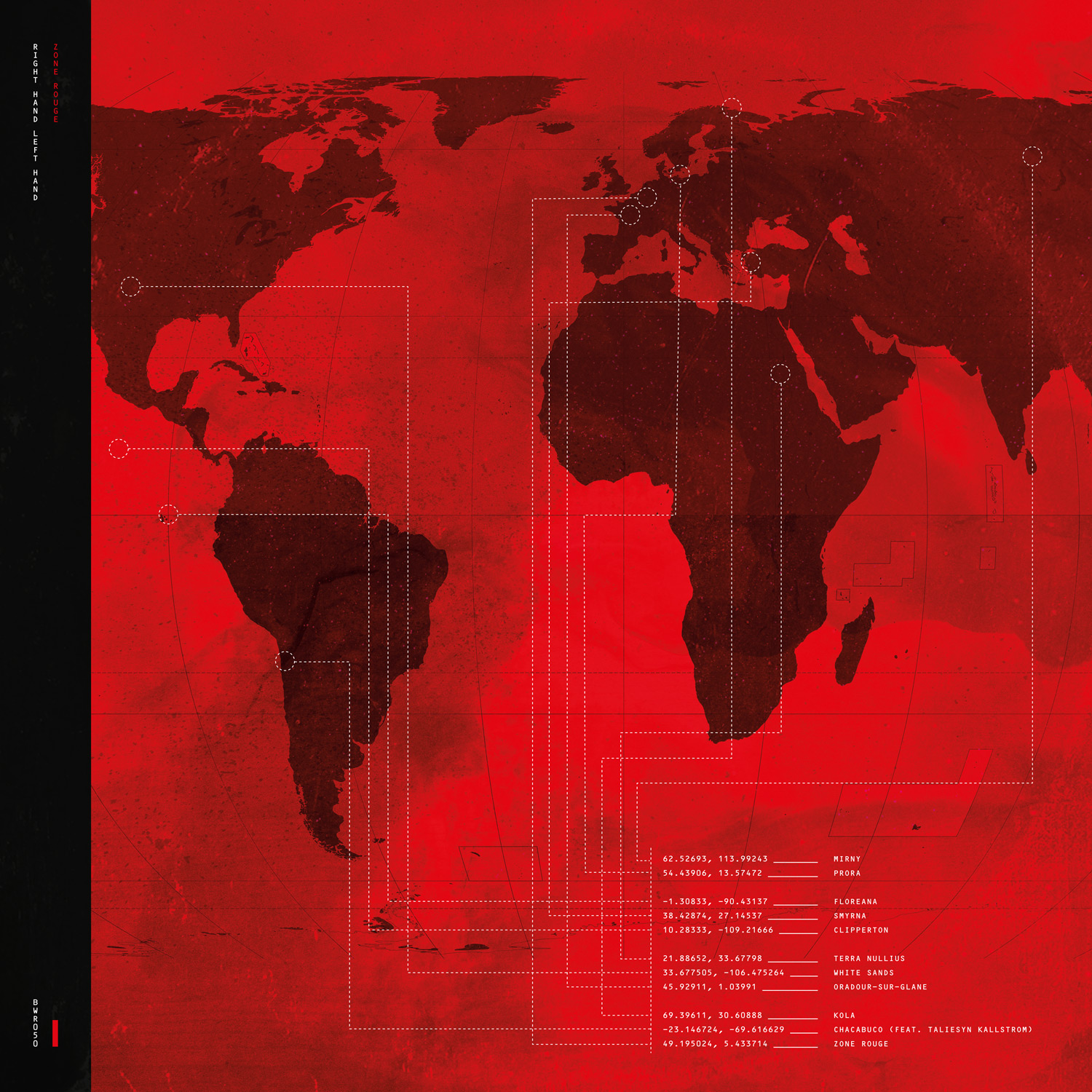

He fished a transparent vinyl disc from a mound of stinking garbage, wiped it with his ragged shirt sleeve, and inspected it. Disc two. There had been a map on the record’s cover, wherever that now was. An early draft of his review, mislaid during a violent skirmish with a mob of advertising copywriters from the twelfth floor, had begun with the observation that the best books have little maps at the beginning, but that this was a trope that had rarely, if ever, been exploited by the recording industry. More albums, thought Bond, should contain maps. Thinking back, he recalled not only a map – a Mercator-style depiction of the Earth’s geography, with further distortions returning Africa and South America to something like their true scale – but also a latitude/longitude reference for each track. He squinted at the soiled remnants of the label and made out the title, ‘33.677505, -106.475264 – White Sands’.

There had been no electricity anywhere below the thirty-fifth floor for weeks now, therefore Bond had to rely on the fading impressions the LP had left in his memory. But he had liked this track a lot, so it seemed like a good place to start. It had begun with the kind of thuggish riff the one might describe as muscular. These bulging slabs of rock-and-roll protein sat either side of a central thorax composed of a succession of stunned silences punctured repeatedly by disturbing knife blades of sound. Probably a sample of a guitar chord played backwards or something like that, thought Bond distractedly. But the timing was impeccable. Each flash of steel in the darkness was both identical and suggestive of a fresh horror. Or the same horror observed from a different perspective in time. White Sands, he remembered from the press release, was the location of the first atom bomb test in New Mexico, so he supposed this to have been the aural representation of the flash of the explosion, a kind of attempt to indicate something essentially unrepresentable.

Bond took another bite from the Alsatian’s hind leg. It’s all about time isn’t it, he thought? It seemed like an important question. When was the music? Was it the moment of the explosion itself? Or were these sounds a Dr Stranglelove style montage of the idea of the explosion, drawn from some newsreel archive of the musical imagination, and unfolding in some timeless zone of representation? Or was he barking up the wrong tree entirely? Perhaps, more prosaically, the musicians had in mind merely the general topography of White Sands, an anonymous and remote stretch of desert, remarkable only as a passing, half-forgotten binge in humanity’s ongoing quest to slake the death instinct.

There were scant lyrical reference points to navigate by. Only one track, ‘-23.146724, -69.616629 – Chacabuco’, could really be called a song, its repeated refrain of ‘Do you remember us?’ a desperate plea to be noted. Chacabuco had been a Chilean nitrate mine, abandoned, and then revived as a concentration camp during the Pinochet era. From his expensive cell, slotted randomly into the sheer cliff face of the high-rise, Bond surveyed his own crumbling horizons and tried to imagine Chacabuco, out there somewhere, still surrounded by land mines, but currently being restored by its one remaining inhabitant. That’s a lot of history to pack into five minutes or so of post rock. Do we remember them? Can we? Taliesyn Kallstrom’s defiant voice remained clear in Bond’s mind, raw with emotion, commanding and accusatory. She had found something beautiful there, something which needed expression. He had no doubt about that. If it fell short of reality, as it must, there was art in it nonetheless and that had to be worth something.

Squatting beside his makeshift fire of telephone directories, it occurred to him that the title track, ‘49.195024, 5.433714 – Zone Rouge’, embodied something of the paradoxical relationship between time and space they were exploring here. The Zone Rouge designates the site of certain First World War battlefields in France – specifically places where the volume of ordinance deployed has contaminated the ground to such a degree that more than a century later they remain out of bounds. Again, when is this music? When is Zone Rouge? A hundred years ago, or the day after tomorrow? Before or after the fact? But the fact stubbornly continues – an act of violence on a loop, persisting just below the surface the of the earth, just waiting for the stroke of a foot on the pedal.

Bond stared in frustration at the mute circle of plastic in his hands. If only he could decipher the grooves visually, he’d have access again to its pleasures. Perhaps one day, an arachaeologist would find it and reverse engineer the record player from this very recording. What would they make of us?

Was the record a memorial, he wondered, not without distaste? Other names came back to him, a roll call of ecological and human destruction – Clipperton, Oradour-Sur-Glane, Mirny, Floreana, and the Zone Rouge itself – names for the most part unfamiliar, others a sinister echo of some ancient bit of reading, obscured in a dim corner of Bond’s mind. He cursed the loss of the press release and hoped that Cummings and his colleagues at God is in the TV would be forgiving, or that he could somehow occlude his ignorance behind a veil of critical gravitas. It hadn’t felt like a memorial exactly. There was, as with all of Right Hand Left Hand’s music, a kind of frenetic dynamism, an ineluctable, looping energy that swept you along with it. That morning, in the corridor outside, Bond had found a scrap of paper in his own hand bearing the heading ‘10.28333, -109.21666 – Clipperton’. His illegible scrawl pointed to a half-formed comparison between Slint and Dick Dale and his Del-Tones. Good, he nodded. He could probably work that up into some kind of preposterous analogy later. People seemed to like those bits. As with the greatest eschatological writings, he observed, from After London to Cat’s Cradle to On the Beach, Zone Rouge often conveyed a sense that its authors were rather enjoying themselves.

He recalled the interview he had conducted with Right Hand Left Hand’s Rhodri Viney. It had only been a few months ago, but it might as well have been on another planet. Viney had spoken then of Zone Rouge, albeit obliquely, and had seemed earnest about the project. He had even given Bond a lengthy and largely neglected reading list. Viney had struck Bond as modest and thoughtful. The kind of quietly spoken, bespectacled man you’d nod at in passing in one of the corridors on a lower level and promptly forget about. He’d been discussing some music he’d made under the aegis of his solo project, Ratatosk, and although very different in style, there were numerous parallels of tone. Both possessed a similar sense of the melodramatic grandeur of the landscape and of humanity’s failure and general unworthiness to sustain its own existence within it. And if there was sometimes irony there, it was irony of the best kind, an unblinking, sincere irony that dared you to find any of this amusing.

Yes, thought Bond with a self-satisfied smirk, eschatology hasn’t been this much fun since the Sisters of Mercy. Zone Rouge is, above all, an album to be played very loud indeed. It really gets the blood pumping, he decided and regretted its absence as it would have been quite the swashbuckling soundtrack for his new life here in the high rise. He needed to think of some clever line the band might put on a poster. Usually, prior to the submission of an article, he’d go through the text and try and identify anything like a quote that might be useful for PR purposes and either delete it or find some way to turn it into such a backhanded compliment as to render it moot. In this case, though, he was happy to overcome his usual aversion to other people’s commercial considerations. Cummings could probably do with a break, and he’d rather liked Viney, and wanted to do him a good turn. Besides, all things considered, Zone Rouge deserved to find the widest possible audience. He resolved to give it his whole-hearted endorsement.

He would think of something very nice to say about the album in the morning he decided, as the sun went down on the derelict, trash-strewn car park thirty floors below him. Tonight however he had an invitation to join a raiding party with a trio of airline hostesses and a documentary film-maker. Bond delicately tossed the last remnant of his supper over the balcony and prepared to join his new friends. Yes, things were working out very well in his new home. Very well indeed.

* With sincere apologies to J.G. Ballard and, well, everyone.