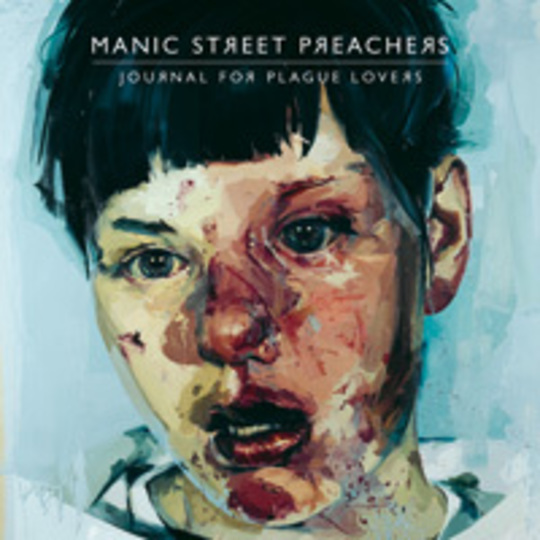

When I was a teenager in the mid-2000’s first becoming obsessed by music, Manic Street Preachers seemed to be to just another Coldplay. Bland, safe, yawn-inducing. I have vague memories of being 6 and hearing ‘If You Tolerate This…’ on the radio and then the next time they appeared on my radar was in 2007, when they released ‘Your Love Alone is Not Enough’, which was enough to condemn them to the MOR prison which housed Embrace and Snow Patrol. It wasn’t until the release of Journal for Plague Lovers in 2009 that I learnt about Richey Edwards and the complex history of a band whose career seems to go in acts, with some changes more tragic than others.

Before Richey Edwards, Manic Street Preachers’ lyricist and guitar player(ish), went missing on February 1st 1995, he gave each of the band a folder. Inside the folder were dozens of lyrics, prose writings, drawings and paintings. At the time, the band did not perceive anything unusual about this, which Nicky Wire has since said ‘was a bit stupid really’. But in hindsight, there was something different about these folders, housed inside a Bugs Bunny binder with the word opulence carved into it, it contained a sense of finality. It took 14 years for the band to use Richey’s final words, but the resulting album was worth the wait, the record is sonically pulsating and intellectually dazzling.

Journal for Plague Lovers is defined by Richey; by both his formidable writing and his absence. This is the only Manic Street Preachers album in which all the lyrics are written by Richey alone. Richey’s writing on The Holy Bible was maximalist; it was an intensely cerebral collection of lyrics – complex, daring but still contained within a pop structure. They were also extremely dark, discussing everything from self-harm to capital punishment with a healthy dose of the Holocaust in between. It must be noted that The Holy Bible’s lyrics were not the sole creation of Richey, which over years of mythologising has become accepted, but 30% were written by Nicky Wire.

The lyrics for Journal For Plague Lovers are still complex in their ideas but much more restrained in their language and length. Some songs feature a verse repeated and a chorus, which sounds almost like individual haikus stuck together. While the construction of the lyrics themselves feel very different to The Holy Bible, there is a definite continuation of themes. The album dwells on porous self-identity, mental illness, the seeming impossibility of authentic relationships – all strung together with pop-culture references and literary allusions. It is difficult with many of the songs to draw any definite meanings, the lyrics too abstract or fragmented. But the album feels all the more beguiling for it, like we’re listening to a mind working several moves ahead on the board. Rather than songs meaning this or that, you instead catch glimpses of understanding within the density of the writing.

‘Facing Page: Top Left’ seems to make allusions to Richey’s time in hospitals and the people and disease he encountered; ‘Here is oblivion bathed acid red/Mute oily discolor, skin cancer, calories.’ ‘Marlon J.D.’ appears to be a reworking of the Marlon Brando film Reflections in a Golden Eye but then Richey then seems to fuse in elements of the life of James Dean, to create something otherworldly and violent:

He stood like a statue

As he was beaten across the face

With a horse whip

Where the wounds already exist

Some songs are more concrete, ‘Virginia State Epileptic Colony’ was an actual hospital-cum-prison in the Virginia early 20th century. Richey imagines the lives of the inmates as they deal with the daily oppression and supposed treatment; ‘They sit around tables rendered dumb/Colored sticks of chalk are passed around.’ ‘All is Vanity’ is wonderfully nihilistic, gloriously rejecting the thing central to late stage-capitalism – infinite options; ‘I would prefer no choice/One bread, one milk, one food, that’s all/I’m confused, I only want one truth.’

But the album is also home to some genuinely hilarious writing, which is something often overlooked about Richey, I genuinely think ‘Archives of Pain’ from The Holy Bible is the funniest song ever written. Take this from ‘Me and Stephen Hawking’, ‘Overjoyed, me and Stephen Hawking, we laugh/We missed the sex revolution/ When we failed the physical.’ For a writer often considered the epitome of dark and tortured, Journal For Plague Lovers shows Richey’s talents for comedic writing. ‘The dwarf takes his cockerel out of the cock fight’ from ‘Peeled Apples’ always brings an absurd smile to my face.

The album finishes with ‘William’s Last Words’, which given the circumstances of Richey’s disappearance, seems nakedly confessional. But this song was edited down from a full page of prose into a gorgeous, stream-lined lament; with the almost tender last line ‘I’d love to go to sleep/And wake up happy.’ It seems churlish to say this is not about Richey’s depression, but also to view it as a Plath-esque confession is to seek clarity in a situation where there is only murkiness.

On the Manic Street Preachers website, there is a section composed entirely of lists; from best Heavenly album to best trumpet maker. Journal For Plague Lovers comfortably sits in the top 2 of best Manics records. It’s an album with a strange feeling of sounding both vitally new but achingly historical, caught desperately between past and present. It was brief but Richey Edwards wrote some extraordinary lyrics, and Journal for Plague Lovers is a shadowed glimpse into a mind that raced at speeds few of us can imagine.