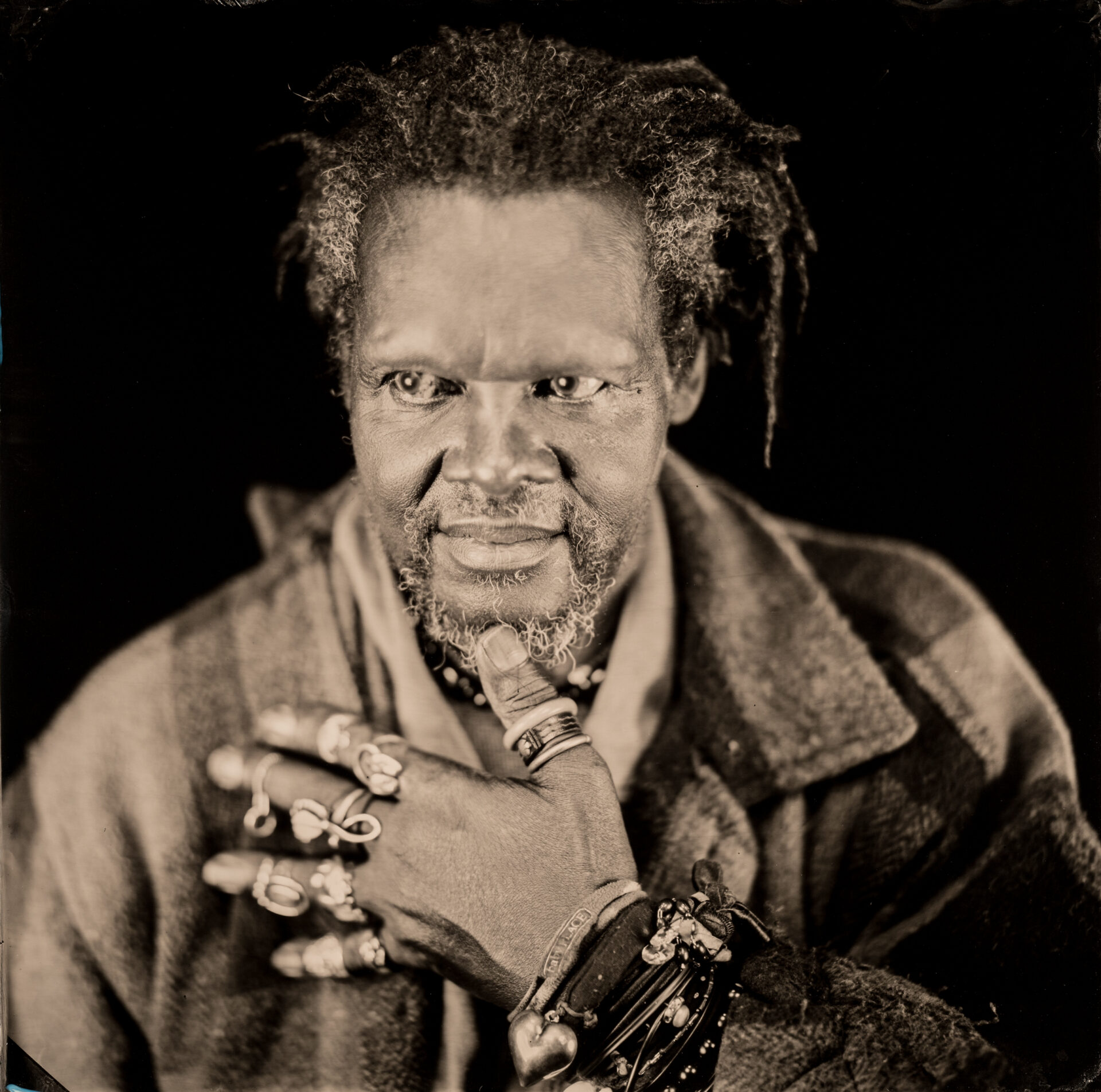

Lonnie Holley makes his way through the chancel of St John on Bethnal Green. His glasses rest professorially on his forehead, left hand encrusted in rings and bracelets, eyes alive and twinkling beneath short, silvery dreadlocks. Nearly seventy years old, he moves slowly and carefully, seats himself at his keyboard and collects himself to perform.

We’ve just heard a few words of introduction from Holley’s manager, and so we know a little of his backstory. We know he was the seventh of twenty-seven children, born into chaotic poverty in Jim Crow era America, and that he discovered the transformative power of art in 1979 after a house fire took the lives of his sister’s two children. We hear also that his work is now collected by museums across America, and how, almost by accident, mesmerising recordings of his musical performances found him an audience outside the art world and the communities where he teaches. That this is the last night of their European tour, and we’re in for something special.

His bandmates, Marlon Patton on drums and bass pedals and Dave Nelson on trombone and loops, play him on stage to one of their own compositions. The piece is stately and diaphanous, creating an appropriately meditative, visionary atmosphere. Holley leans into his twin mics and intones, half conversationally, “I was thinking about the development of humankind…”

Like most of the music we’ll hear this evening, the song that follows is improvised, its lyrics ranging from speculation about the origins of humanity, though to air travel, life in the jungles of Africa, climate change, spaceship Earth, and whatever topics present themselves to his restless imagination. He even includes a verse about how glad he is to be in London singing for us tonight.

There’s no neat way to encapsulate exactly what it is we’re hearing. Some would just call it the blues, and they wouldn’t be wrong – the haunting, inarticulate vocal juggernaut of Charlie Patton comes easily to mind. But there’s touches of Sun Ra’s limitless preoccupation with the cosmic, of Tom Waits in his guise of holy fool, and even of Alice Coltrane’s wayward, cosmopolitan spirituality, or The Last Poets’ devastating turn of phrase.

The next song riffs on the line, “I had to go on,” and it’s about all the times you can’t go on, and yet you do, because you do. Later, we’re in space, where, “They wouldn’t let us on their spaceship / so we had to make our own”. Another song directs itself to the doors of the church, and to the terror and pity of the world outside, and another to the dehumanised hectoring of the daily news cycle.

Patton and Nelson have been playing with him for a few years, since Holley’s extensive contributions to their 2016 Nelson Patton album, Along the Way. Each piece of music starts slowly as they wait to see where Holley leads them, sometimes with a little too much hesitancy, until at some point, something kicks in and there’s a completely realised thing happening in front of you. They’re symbiotic in the way that jazz musicians have to be. They barely make eye contact, Patton gently caressing his drum kit, one foot on a row of bass pedals to his right, while Nelson explores the untapped sonic potential of the trombone.

Everyone and their mother is looping stuff these days, but trombone? Yup, that’s a new one, at least for me. Notes are layered into guttural chords, played backwards, and looped under and around a voice that seems endlessly startled by its own ruminations.

Then out it comes: “I went to sleep / I went to sleep / anticipating / a dreaming”, and we’re into the degraded, ugly centrepiece of last year’s superb LP, MITH, and the apocalyptic fury of ‘I Woke Up in a Fucked-Up America’. In keeping with the improvisational texture of his live performance, there are some twists – tonight the dreamer longs only to return to his dream, to complete his blissful escape.

But we’re reminded, naturally, of Dr Martin Luther King, and of W.B. Yeats’ line, ‘In dreams begin responsibilities’, and of the dream that impels us to resist, to transform ourselves and our reality. There’s no more hesitancy, no more waiting around. All three of them know where this one is going. It gets loud and frightening, and the battered walls of St John in Bethnal Green, with their patches of polite Anglican dilapidation, peeling paint, and the cruel, atheistic realism of Chris Gollon’s Stations of the Cross, can barely contain the indignant force of this righteous, awakening monster.

He finishes on a joke. I won’t spoil it, but it involves Siri. As you can imagine, Lonnie Holley has a lot of questions for Siri, not least of which is just what the hell she thinks she’s doing to him. Cast as the subject of a satirically deployed misogynistic song-writing trope, Siri is in for it tonight.

It’s a final chance on the last night of the tour for the three of them let rip, this time enjoying all the theatrical, over-heated passion of a disappointed lover. Tapping into an old blues tradition of coded protest, Holley pits ironic rage against a device that tracks us, spies on us, takes up our time and attention and money and promises everything, while understanding only as much of us as is necessary to take, take, take. It’s an old question – essentially baby, why you treat me this way? – but musically, we’re way beyond the blues. It’s almost industrially heavy, and comes too quick and hard to really take it in.

Lonnie Holley cuts an inspiring and unique figure. He’s a convergence of music and art, sure, but there’s something more than that going on, and it’s not enough to dwell on the rootsiness of his music. He offers a powerful, contemporary take on a grand tradition of black music, and as a visitor from the sticks, I’m a bit shocked that there were tickets left on the door for this show. Has word not got round? London, where were you? As he wraps up, we’re on our feet for a standing ovation. A haunted and haunting voice, Lonnie Holley is one of the incredible, dreaming trees of the forest, at once tragic and playful, elemental and human.

Main photo credit – Timothy Duffy