Yesterday we awoke to the shocking news that Keith Flint the front person of the Prodigy had been found unconscious and pronounced dead at his Essex home, at just the age of 49. His bandmates called him an innovator and a legend. It later emerged that he took his own life, a tragic end for a man who possessed so much energy, his restless spirit and force snuffed out before its time.

Maybe he wasn’t always integral their sound but Keith Flint was always the Prodigy’s talisman, from the early days when his dancing, long hair and rubbery features caught the attention on stage and in their early videos. Later on, he would give dance music a face in a sea of faceless DJs and white labels. His iconic performance in the video for ‘Firestarter’ was both abrasive and thrilling. Gurning and contorting his body, he was embodying the rebel spirit and a spat out anarchic vocal that would scare your parents and delight the kids. Headbanging in a disused tunnel, a cartoonish yet utterly compelling image, a neon spiky haired punk who had lit the fuse on the dance floor. He was also a ball of energy on stage, less a singer more an instigator, and cheeky vocal sparring partner for Liam Howlett’s frenetic collage of sounds. Particularly on their first three albums(‘Experience’, ‘Music for the Jilted Generation’ and ‘Fat of the Land’), The Prodigy chewed up the aggressiveness of punk and bled it with the big beats of dance music and regurgitated it by way of bhangra, reggae and hip hop. Sewn with every sample you can think of, reclaimed and reassembled for the charts. And whilst their latter work may sound a little dated and too wedded to the 90s now on those early albums they were truly a genre-blurring collective who uniquely inspired kids from every scene. I’d lost touch with them in recent years but in the ’90s they brought rave to the mainstream stages and in the process soundtracked a generation. According to those who met him he was vivacious and charming off stage on stage, Keith felt like one of us, embodying our visceral need to dance and scream. His warrior spirit never dimmed. Keith Flint may be gone but he will never be forgotten. (Bill Cummings)

Here we pick some of our favourite Prodigy songs and memories of the man in tribute to Keith Flint.

Charly

‘Charly’ doesn’t owe a lot to Keith Flint in the traditional sense – he doesn’t have any vocal or songwriting credits. But he’s there in the video, which nearly thirty years on still looks like what clubbing can feel like. It’s a mish-mash of strobe-struck performance footage, chemically-induced dance moves and crude animations. Flint’s facial expressions are enticing, sinister, playful and uncompromising all at once. Liam Howlett’s productions may seem too strange to code as pop music, yet The Prodigy was once one of the biggest dance acts in the world. Part of the reason for that is Keith Flint -so much charisma and energy, his position as de facto frontman made them a captivating presence in a world dominated by anonymous 12″ singles that sold thousands in the wrong kinds of record shops. Rave was never meant to be mainstream, and perhaps without The Prodigy, it never would have been – and without Flint, it definitely wouldn’t have. (Scott Ramage)

Out of Space

The Prodigy’s debut album, Experience, paved the way for the British rave scene of the early ‘90s and one song from the album which has been a live performance favourite for the band throughout their near-30 career year is ‘Out of Space.’

The song in itself was a hit, sampling reggae record ‘Chase the Devil’, but for me, the video for the track was just mesmerising. Featuring a cavorting Keith Flint in the days before his trademark spiked hair, back when his role was as the group’s dancer, the inverted negative-style editing of the video intertwined with the occasional ostrich footage really did allow for a drug trip-like experience. The dancing was simply infectious, with Flint appearing in white overalls, wearing rubber gloves, a mouth mask and sunglasses like a character from a low budget horror movie; even now, watching it nearly 30 years later, it still feels as trippy as ever. (Charlotte Westwood)

No Good (Start the Dance)

Along with ‘Out of Space’, ‘No Good (Start the Dance)’ is my favourite single released by The Prodigy. ‘No Good’ lifted from the classic album ‘Music for a Jilted Generation‘ is what the kids of today would call a banger, that breached the top five in 1994: with insistent synth stabs and a cacophony of beats, all deftly genre spliced with a female vocal sample from Kelly Charles (1987). Apparently, Prodigy mastermind Liam Howlett initially had doubts whether to use the sample because he thought it was ‘too pop’ for his taste, good job he left it in because it’s what anchors this song and makes it particularly memorable and stands out from the crowded rave releases of that era.

By the time they released ‘Fat Of the Land’ and the visceral thrill of singles like ‘Firestarter’, and ‘Breathe’, The Prodigy were a household name, their exhilarating genre-blurring sound and Keith’s cartoonish vocals, they united the tastes of townies, moshers and indie kids in the 90s, in an era when musical tribalism still held sway. But for me, this is the addictive tune that defined them. Its black and white video featuring knocking down walls in a cellar and Keith’s memorable dancing reflects the period when ravers took up disused spaces and fields and created their own parties something which may be making a comeback with the closure of so many venues and clubs. (Bill Cummings)

Firestarter

When people talk about the spirit of punk being dead, what they really mean is the role of rock as the dominant form of protest music. But the spirit of punk lives on. Not in the shadows of deathless Sex Pistols imitators and rock posturing, where imagination and innovation are replaced by said moves and over-familiar tropes. But it lives in the angry class warfare of grime, the abrasion of dubstep, the disorienting affectations of every avant-garde Soundcloud producer. In 1996 I was eight years old, and ‘Firestarter’ was astounding to my youthful ears. I knew dance music as the sound of chart-pop songs like ‘Dreamer’ and ‘Don’t Give Me Your Life’, but this was entirely different: those snarls of guitars, rushing snares that sounded like falling from a height, bass rumbling like thunderclaps from Hell. All capped with Flint’s demented, committed performance. As an adult, it’s impossible to view as anything other than pure camp, a pantomime performance of cartoon devilishness designed to antagonise, but as a child, ‘Firestarter’ was so odd, so confrontational and so aggressive – it fascinated me.

Punk and dance met before: Leftfield‘s collaboration with Sex Pistol John Lydon and his vague, pseudo-cynicism on ‘Open Up’, a grab at serious attacks on celebrity and capitalism. But ‘Firestarter’ took that path to its extreme conclusion, by being so abstract – it’s a melange of grunting nonsense, a revel in decadent boorishness. It’s hard to take “Firestarter” seriously now: The Prodigy are part of British dance music heritage, ‘Firestarter’ was a Number One single that’s become a student disco anthem, maybe even a wedding favourite. But I envy anyone young enough and unfamiliar, who gets to experience the sonic thrill of hearing it for the first time. The Prodigy didn’t remain important to me – I discovered Proper Serious Dance Music not too much later, and I can hear a lot of their influence in music that I actively dislike (the petulance of nu-metal, the enforced wackiness of novelty dance music, the brashness of brostep). And they were never really taken as seriously after this – too much novelty and obnoxiousness. But at this moment, the spirit of punk thrived, as The Prodigy showed it wasn’t about guitars and fashion. It was about challenging expectations, avoiding respectability and carving out an original and thrilling sonic space. (Scott Ramage)

Breathe

Dear God. Please don’t let 2019 turn into another year like 2016, when celebrities dropped like flies and every time you saw a name trending on Twitter you started fearing the worse.

It’s still sinking in that Keith Flint is dead, and even worse, that he has taken his own life. A discussion on male suicide is due for another time, but now I’d like to celebrate one of Flint’s greatest moments.

It would be dishonest to claim that I was a Prodigy fan from the off, because I wasn’t and for much of the first half of the 1990s, I didn’t get much dance music. This was far more to do with me being a moody teenager, seeing boundaries that weren’t there, and nothing to do with the music itself (though the fact that I can’t dance for toffee may be something to do with it). I didn’t care much for these tracks at the time – I now recognise them as representative of much of the great dance music coming out of Britain then, that is just as important as the Britpop scene. And indeed, the boundaries started to get blurred, all for the better.

After ‘Firestarter’ had topped the charts in 1996, this was followed by the even-more exciting ‘Breathe’ which mixed Joy Division bass-lines, punk energy, seemingly several different styles of dance music (I was learning by now) and Keith Flint and Maxim leading this brilliant monster out of our stereos. Perhaps like Massive Attack, they were a British band who managed to combine so many different styles to produce something that was reflective of where Britain’s many tribes were coming from and how they had come together. This was the point at which I started to rethink my whole attitude towards dance music. There may have been older style ravers grumbling about indie kids moshing down at the front of Prodigy concerts, but to me this symbolises the barriers coming down and pointing the way to the future. There’s a lot of music from the mid 1990s that has been played too many times now, but ‘Breathe’ is still thrilling, a call to arms and the urge to leave it all behind. Thanks Keith. Rest in peace. (Ed Jupp)

Warrior Dance

Frustratingly, the only time I saw them live was at Glastonbury in 1997. Keith was on fine form, even if the electrics gave out after the second song, and Dennis Pennis had to keep things going by singing to the crowd in Hebrew (no, really). I headed off to China a couple of days later, but not before I picked up a copy of Fat Of the Land, their third album, released the Monday after Glastonbury.

Perhaps I drifted apart from The Prodigy after this period – I didn’t much care for the ‘Baby’s Got A Temper’ single in 2002 or the Always Outnumbered Never Outgunned album from 2004 (which didn’t feature Keith), but my interest was reignited with 2009’s Invaders Must Die album and listening to two of the singles from this album again, they deserve to be shared. What also struck me as interesting – I was teaching by this time – was how many of the kids I taught loved The Prodigy, too. (Ed Jupp)

When a figure of such gravitas leaves us, it often feels as though they left at the time they were most needed. Keith Flint represented a true British everyman – not the toxic, pseudo-nostalgic, xenophobic caricature that has represented us for the past few years. He was the plucky, gritty urbanite and the tweed suited country gentleman and pub landlord. He could fly the flag and not be a dick about it. No matter who you are in Britain, there’s a little bit of Keith Flint in you, in one way or another. He was the rebellious teenager I was, sneaking out to raves where I’d meet (I kid you not) my English teacher who looked like a Quentin Blake illustration in a tweed jacket. I wonder how many other musicians will be eulogised by both Dizzee Rascal and James Blunt. A former neighbour of mine went on hunts with him. Because he was against fox hunting, his pub was constantly picketed. I found that to be so emblematic of him: quintessentially British without the nasty bits.

We Live Forever

Musically, he was the gateway drug to the wider electronic realm for many a rocker, marrying punk’s attitude and abrasiveness with amen breaks and filthy 303 basslines as though they were always meant for one another. You’d be hard-pressed to find a crowd as diverse as The Prodigy’s. More than just ‘Firestarter’- from the explosive ‘Omen’ to the pounding, tragically title‘We Live Forever’, via the swaggering, Queenadreena-esque ‘The Day Is My Enemy’ – The Prodigy were always potent, always relevant, always outnumbered, never outgunned.

Aim 4

He was more than just The Prodigy, too; I fondly remember his rockier side-project, Flint and their sneering “Aim 4”. Check it out if you haven’t heard it already. Acts as diverse as Pendulum, Death Grips, and Bring Me The Horizon owe Keith Flint a hefty debt.

On a personal level, Keith Flint was an unlikely uniting force in my dysfunctional family home while I was growing up. When my mother remarried to an alcoholic mechanic who took an instant disliking to me and everything my angsty twelve-year-old self stood for, I made it my mission to either scare him away or force him to accept me for who I was. Like any British kid in that position, I turned to Kerrang for inspiration, and that inspiration came in the form of The Prodigy. While my younger brother was more concerned with the alligator in the ‘Breathe’ video (he giggled every time it fell off the bed at the end), I took inspiration from Keith Flint’s punk wardrobe and his dark eyeliner, which became my war paint. When my new stepfather moved his CD collection in, imagine my horror when “Fat of the Land” was at the top of the pile, followed by Nirvana’s “Nevermind” and Led Zeppelin’s “IV”. I now had common ground with my mortal enemy. He was suddenly human. Since that moment, I have always sought common ground when faced with hostility. I have Keith Flint to thank for the friends I’ve made with this approach.

The only troubling thing I’ve read in relation to Keith over the past 24 hours is that he was the last rock frontman in electronic music. I can assure you that he’s inspired so many of us that he’ll be the exact opposite. He’ll be the father of a movement. Just watch.

(Aidan James)

Rest in Peace, Keith Flint

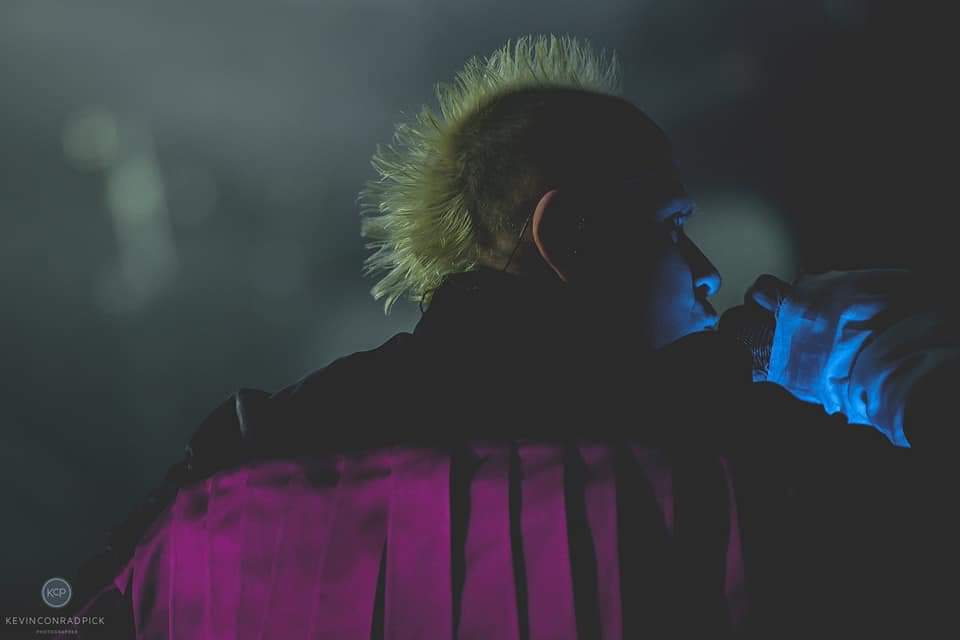

Image by Kevin Pick