On Wednesday it was announced that the NME was to cease its print edition after a 66-year run, and with it ends a chapter of music history. Sadly it had become inevitable given its steep descent into a barren, free lifestyle title that nobody seemed to care about anymore in recent years.

What you consider the peak years of the NME probably depends upon your age, alternatively the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, ’90s? Even parts of the noughties are cited as its peak years. It might be tied up with nostalgia but the memories of the NME paper will be as mixed as the eras. Bratty, insurgent and rebellious at its best from firebrand punk chroniclers Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons in the 1970s to the excellent prose of Nick Kent.

As Charles Shaar Murray recalls: “Up until 1971, the NME was still run on the lines of a successful pop music magazine of about 1964. Cilla [Black] was in the charts and Cliff [Richard] was in the charts. What Cliff and Cilla had for breakfast was the sort of thing they published; it was hopeless.” He continues: “It was well behind The Melody Maker, which was a far sharper, much better magazine than NME – it was a dying entity.” At the time, NME had been given a prognosis of “12 issues left” before it was finished for good. Back then, the magazine had reached a crisis point – selling less than 60, 000 copies a week. “The whole thing was up for grabs,” Charles Shaar Murray remembers.

In the early part of the 1970s, according to Tony Tyler, the one person who made the NME what it was then was Ian MacDonald. “The whole tradition of irreverence that everyone subsequently copied all came from Ian. There was once a group called Argent led by a very competent organist called Rod Argent, but they were rather dull, and Ian saw the essential dullness of this group. I can’t remember who wrote the piece, but he just took the same picture of Rod five times. The headline was ‘The Five Faces of Rod Argent.” All this sounds rather tame today, but it was people like Ian who actually started doing this first. People were still being tremendously reverent about anyone who was famous.”

Others like David Quantick and Danny Baker who lent an authority and infused their writing with that excitable feeling that there was a mischievous fellow music fan by your side as you discovered the latest single or new band; for teenagers who grew up in Satellite towns pre-internet the NME was their window to another world, a lifeline to a culture beyond your hometown. As David Stubbs (aka Melody Maker’s brilliant Mr Agreeable) puts it NME’s paper was also an education, not just in music but opening up the world of possibilities. Writers like Paul Morley and introducing to writers, directors, authors, philosophers entire new worlds to explore and inspire:

“When I was at University I was ostensibly reading English Language and Literature. In fact, I read the NME. It was formative, not just a gateway to new music but also to European literature, free jazz, politics, philosophy, film, as well as validating the best of popular culture from Laurel and Hardy to Hill Street Blues. This was a paper that had Joy Division and Sun Ra as well as Coronation Street on the cover. It was brilliantly pretentious and brilliantly funny. It made me. It taught me that rock journalism needn’t be a tediously hermetic business of assessing guitar bands but a transcendent mode of discourse. It could be about everything. As a writer, you could become – whatever, through your writing. It was the perfect journalistic mouthpiece for the conceptualism and radical ambition of the post-punk era.”

Charles Shaar Murray also recalls that journalists were given previously unavailable access to the stars. “It was relatively informal, free, and easy. Basically, you were allowed an enormous amount of access. As well as doing a formal session with a tape recorder, you would hang out with them for hours.” Remembering an interview with David Bowie that was something special, he continued: “I got invited down to the studio where he was finishing off what eventually became the Aladdin Sane album and was able to watch his recording and hear most of the material from the album – probably before the record company.” At the time, Bowie had publically stated that he wasn’t doing interviews. A privileged position – and experience – that most people would treasure forever.

In 1976, NME ran a piece by Mick Farren that today many people regard as the blueprint for punk. However, Farren himself doesn’t see it that way. “This was the classic era of Keith Moon driving limousines into swimming pools, and the Rod Stewart album with the Polaroids of all the groupies, and your mega-stadium rock band was starting to live like something out of the fall of the Roman Empire. My question was ‘How is it possible for Rod Stewart, with his lifestyle, to write music that communicates to an increasingly impoverished audience on the streets of say, Manchester?’ It wasn’t a matter of starting anything; I don’t actually believe that any written piece of criticism can start anything. What I do believe is that if there’s already something loose in the waters and the air, a piece of writing can crystallise it, can give it a certain coherence.”

Around the same time, Tony Tyler had decided that at 33 he was just too old to be writing about rock music. The NME advertised for ‘Two hip, young, gunslingers.’ Saying of the time: “I’ve been accused of freely unleashing Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons on the NME knowing that I myself wasn’t going to be there. And that’s true, I knew I wasn’t going to be there, but I thought that they were just what the NME needed because it was getting a little complacent. I thought they would shake it up.” He wasn’t wrong!

The then 17-year-old Julie Burchill sought to live up to what the advert had asked for – with great gusto. “First, they tried to send me out to interview people, but I was so shy,” she remembers. “I learned very quickly that if you put amphetamine sulphate – and there was a great deal of it about in those days – into people’s tea, then they talked a blue streak, therefore taking away the necessity for me to ask them questions. I took to doing this, and unfortunately, I was caught doing it to Country Joe McDonald. The record company person went back and told Nick Logan and I wasn’t allowed to go out and interview anybody else because I was thought to be irresponsible.” Of course, things changed again. No doubt if an aspiring rock writer was to pull that kind of stunt with whichever band has topped the lot this week or month, not only would they not be allowed out to interview people, they’d most likely find themselves behind bars and jobless.

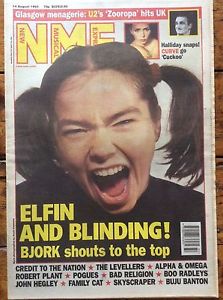

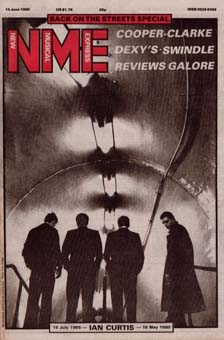

Iconic interviews and front covers featuring the Smiths, Joy Division, Public Enemy, Manics, Suede, Elastica, bis, My Bloody Valentine, Super Furry Animals, New Order, Bjork are unforgettable.

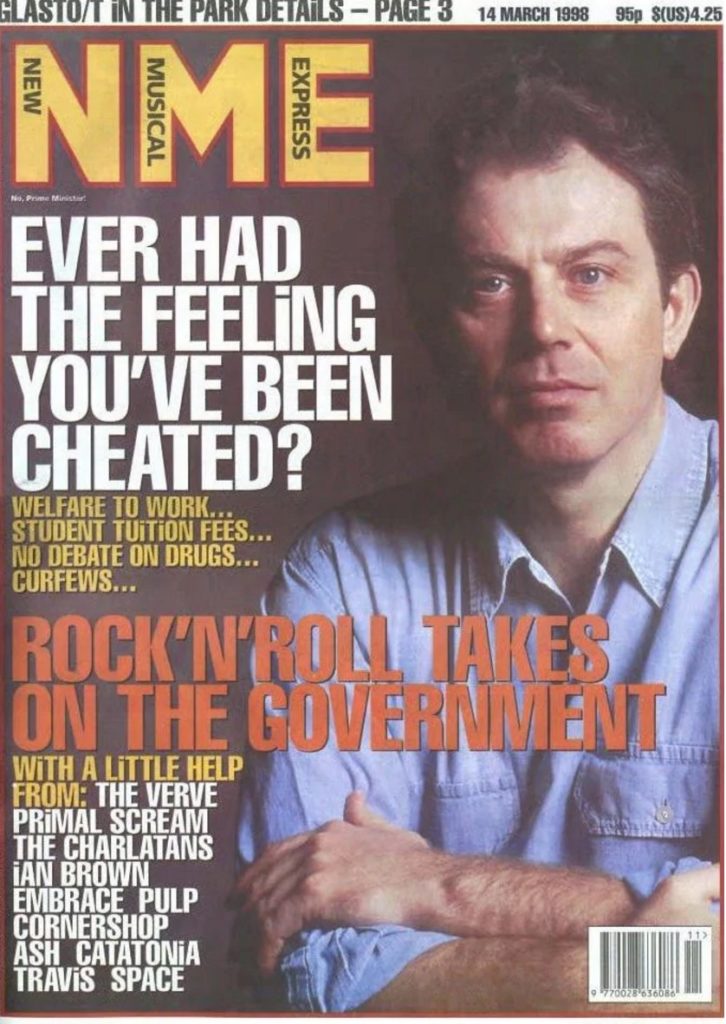

The era I remember most was during the 1990s with the witty, acerbic and irreverent Steven Wells and Johnny Cigarettes their savaging pieces were as hilarious and riveting as the hyperbolic articles about bands they praised to the skies. The issue I remember most was the anti-Blair edition in 1998, not long after NME was bought by IPC media and never again would it be so political and abrasive. It shrank back into its box in awe of marketing numbers and target audiences and it just lost its way.

The steep decline started in their early part of the noughties, laddish editor Conor McNicholas nearly destroyed the magazine in the early 00s with his retro ‘new rock revolution’ seemingly more concerned with haircuts, banter and brands than the music. How many times can you feature the Libertines?

The truth is at various points Sounds, Melody Maker and Smash hits were far better than the NME, less pretentious less in awe of the white male guitar bands, less narrow in their focus, less rockist, more iconoclastic, better written. For as many who loved the magazine there as many people have a visceral hatred of the NME for various understandable reasons, the bullying ego loaded writers attacking whatever was popular, the build them up knock them down culture, the faddy nepotistic coverage, the slavishness to the past, the obsession with what was ‘cool’ rather than what was good whether that’s unsigned or independent artists or huge pop stars or not. The obsession with creating a new scene whether it existed or not. In the end its collapse into corporate compliance and slavishness to brands. They have no affection for it and no regret about the print closure Luke Haines bid it viciously goodbye on Twitter: “Haha. Piss off NME. Everyone who worked for you was a twat. Now you’re gone. Good riddance.” Then followed up with a rebuke of the misfiring predictions, dodgy ownership and snide ‘bullying’ culture of the NME on Radio 4.

But for better or worse over the years the NME was an outlet for outsiders, working-class writers and musicians as Danny Baker put it on twitter:

“The NME never once asked me where I studied. Or what certificates I had. Or where I saw myself in five years. They just sent you to see some band and asked for 400 words on them. If they liked it they’d give you an album to review. Next thing you know you’re in New York.”

The last genuinely good period of the NME writing-wise was helmed by the editorship of Krissi Murison nearly a decade ago, fostering exceptional talents like Laura Snapes and closing the gender gap that existed on the magazine’s staff and in its coverage. To feature in its pages for a new act still meant something, still had cache. I always thought the NME should have used what identity it had left to become a monthly increase the depth, expand its scope of coverage in terms of genre and not just signed artists and improve the writing quality, then there is still a place for print as a special bi-monthly or monthly edition, even in these tough days for advertising, music media and magazines where quality websites like the Guardian and Quietus are asking their readers for funding. Instead it dumbed down became driven by commercial realities and its owners.

While its fair to say that music may not be the vehicle for social change that it once was, so of course the NME doesn’t hold the place in culture it once did. It was mainly the internet that finally did for the NME; the shifts in how we consume music and the gatekeepers we trust, how could it compete with the immediacy of music online? Blogs? Streaming?Social media? They all replaced the rush of picking up your copy and finding out about a new band you had never heard of that week. Indeed even online, words are being replaced by images and videos, this is the shift in music journalism too. By the time it went free in 2015, it was a pale shadow of itself a glorified advert for hair gel, with scant music coverage, a focus on lifestyle and a preponderance to push the latest lad bands or mainstream pop that are covered better and with more depth elsewhere. Still interviews with Jeremy Corbyn, Rihanna and Stormzy showed they could still do depth even if the barren advert-ridden magazine failed in depth, everywhere else as it attempted to be all things to all people, to attract advertising it lost its identity with such little music coverage. There was also a disconnect with the myopic retro focus of its website still obsessed with ridiculous clickbait headlines and retromaniac NME names of the past to drive hits.

All of this saw it plunge into irrelevance as discarded copies were left in tube stations like some sad monument to former glories. Perhaps its the fact that the NME lost sight of what it was great at in its peak years, great writing and iconic images documenting music of its time whether that was from the underground to the overground, independent or mainstream, through the eyes of giddy music fans with a sense of humour. Rather it became boringly either only obsessed with the clichés of music of the past people associated with the NME, the bankers or with a very shallow focus on a celebrity, big pop star or already mainstream guitar bands, it had abandoned the independent labels or the bedroom artists, in the rush to seem relevant and compete with the new digital realities. It was like your dad trying to breakdance. Some argue that the death of NME in print is a sign that guitar music is in decline, given NME’s fortunes seemed to ebb and flow with its popularity and even though there are still great guitar bands around, if you look at the charts there may be something in that, even though its ‘death’ has been predicted many times before. However there are other factors many shaped by NME’s editorial policy and corporate ownership. The writing increasingly became a tick box exercise shorn of the personality and critique, and the writers may have seen the NAME as a step on the media ladder rather than their dream job. Rather than genuinely embracing the increasingly eclectic tastes of its readers and sheer diversity of music online today, whilst recognising a great artist whether they played guitars, a synth or were a grime artist whatever, still embracing their identity and not leaving their audience behind with writing that respected that they were possibly as knowledgeable, if not more than its writers, giving a platform to artists that fitted into that lineage, but not being in awe of it to the point that it became backward-looking and refusing to fully move on and cover different genres, more females more artists from the LGBT community. Instead it fell between two stools, lost its identity, they weren’t in touch with their audience anymore and worst still in its last incarnation it felt like it really wasn’t about the music anymore. They say they will focus more online but that isn’t the point the inky fingered pages of its paper still meant a lot to people of a certain age and its sad to witness how it has shut without even a tribute issue and its writers in the dark. Still, there are NME staff who have lost their jobs and that isn’t to be celebrated.

Alexis Petridis noted in the Guardian that its focus had become too narrow and it had lost its identity and audience as a result:

“Perhaps if it had paid less attention to market research and kept its musical outlook broad, it might have survived longer, better-equipped to navigate an era in which R&B and hip-hop are commercially and creatively dominant, and grime is the underground genre enjoying the biggest crossover into mainstream success. Or perhaps not: the precarious climate for print media, particularly in the music press, doesn’t really encourage any kind of risk-taking. As it is, NME finds itself exiting the stage mourned exclusively by people old enough to remember a time when it seemed important. Sad to say, it seems unlikely you’ll find an 18-year-old in 2018 who cares much whether it exists or not.”

So, as my memories of the NME paper are mixed, for me the sadness of its closure is less to do with the hollow target market obsessed busted flush it had become and more what it used to be, what it represented. That despite its many failings and faults as a title, at its best it gave opportunities to genuinely eccentric people from different backgrounds, to get a foot in the door, to be heard. What the NME paper meant to me when I was young, the acts it introduced us to, the writing that inspired us, the images we will never forget. (Bill Cummings)

Here are some other mixed thoughts on the demise of the NME in print from our staff:

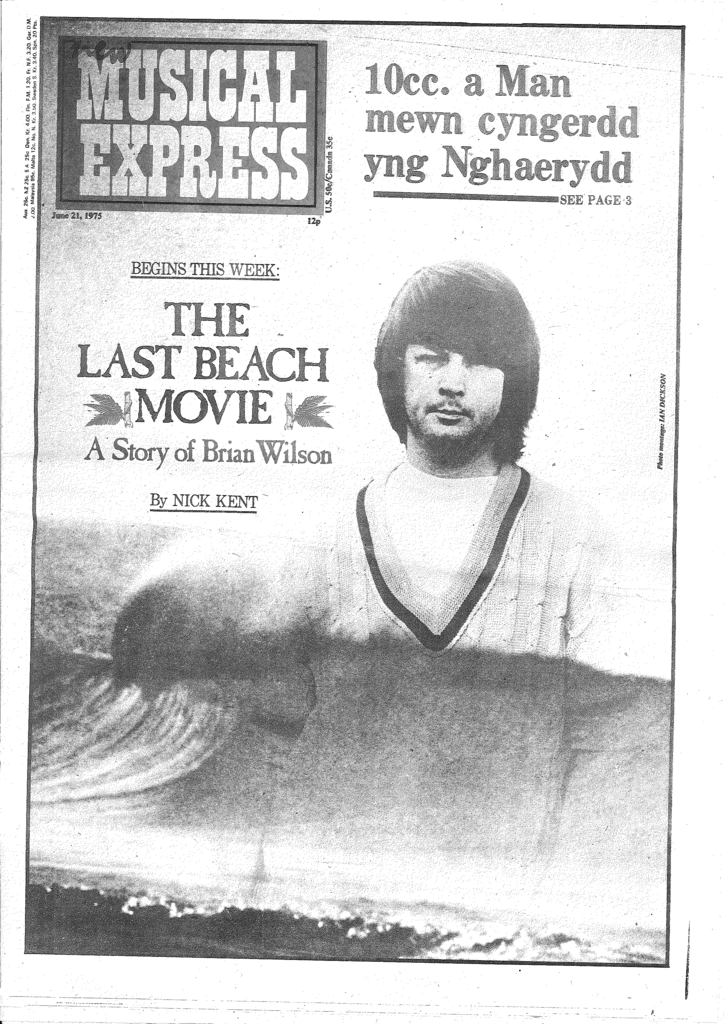

“Growing up with the NME in the early 70s there were many reasons to high-tail it down to the local newsagents every Thursday morning. There was Nick Kent, Charles Shaar Murray and Ian McDonald, producing some of the most influential, informative and inspired musical writing of its day. Kent’s The Last Beach Movie about Brian Wilson and produced over three consecutive weeks lingers long in the memory. Another great reason to get the NME every week was Tony Benyon’s wonderful strip cartoon Th’Lone Groover. It was packed with irreverent observations on the rock’n’roll life from the eponymous hero (and his faithful sidekick Pronto) and a rather ridiculous line in humour that would probably not pass scrutiny by today’s diversity police. The publication sadly lost its way and its relevance but in those heady days between about 1972-75 it was essential reading for any reasonably hip 16 or 17 year old music fan. The influence it had upon shaping musical tastes at that time cannot be overstated.” (Simon Godley)

“At its peak, NME magazine was sprinkled with the greatest acts and some world class music journalism. It was a true backbone, a colossal publication which garnered a fan base and a prolific readership. When the magazine launched in 1952, it rapidly grew as a go to source for music. Many people, young and old, were receiving their weekly fix of quick fired stories and legendary features. With print magazines struggling, NME has become the latest publication to eradicate its print run. This has sent shockwaves through the media, but we all knew it was coming. And although NME became a free magazine in 2015, its popularity dwindled drastically. This was due to too many ads and unnecessary pieces being bundled into its core.

NME became a lifestyle mag, a publication driven by celebrity gossip and pop music. It began to forget its roots, it started to imitate other glossy magazines, leaving the underground behind. This has become a trend for far too many publications. And Independent and underground music is important. But when a popular magazine begins to scorn it, it becomes a problem. Yes there are many people who like to read about celebrities and stories circling these topics. But where is the music? Where is the passion and pride, where are the stories which make us engrossed and compelled to read on. NME lost its enormous readership when the editors felt the need to alter its look and content.

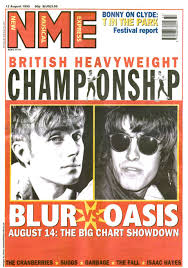

But, with all the pessimism being spread, NME will always be in many musical hearts. It is the magazine which gave us stories about Blur and Oasis’s fight for top spot. Their spat was chronicled by NME, written with verve and groove. There has been many brilliant cover stories created by the editors and writers of NME in the past. The Beatles and The Rolling Stones were given a spotlight in 1960’s, and those stories made NME a household name. Also NME was a brand which had given many working class people jobs in the 1950’s and onwards. It gave many writers a home for their trailblazing music journalism, it spawned many glittering careers. These writers include punk rock expert Julie Burchill and Paul Morley. And although the magazine will be slightly tarnished, its legacy is still intact.

Print magazines are on the edge of oblivion, there’s no doubting that. Even the massive publications are struggling. The internet may be a culprit, as clickbait is a major issue on the net and it drowns out good, honest content. NME and other places online do utilize clickbait, so it could spearhead a drop in views. People want the real news, now. But it isn’t down to that alone, as there’s not as much money to play with. This may stem from the economy or the way these print editions are run. We all remember what happened to two of the most decorated magazines in the world. Metal Hammer and Classic Rock were both cascading into nothingness until they were saved. This created a storm, it rallied a cause. And thank god they’re still running and kicking ass as two pioneering music mags.

“With NME dead as a print run, there will still be a website to enjoy. But we don’t know the angle it will take. This is left to the writers and editors. And it is sad to see such a heavyweight deflate, a significant bible for many, but money talks, and sales are mandatory for survival.” (Mark McConville)

“I bought NME religiously from 1985 until probably about 2012, when it had lost its ability to break music news due to the internet always getting there first. Reviews were dumbed down over the years and the magazine physically got smaller and much thinner and was a shadow of its former self. I always had a fondness for the NME but it has been limping towards the inevitable for a long time now.” (Andy Page)

“The NME was always rubbish really. Writers should have personality but a lot of their “peak era” content was just clenched-fist “fuck normy culture” diatribes that anyone can write without any insight or wit. I mean I’m not sad it’s gone. I’m only 30 so I don’t know its heyday intimately but if the cultural climate is that the internet has leveled out the playing field and the cross-section of society both writing about and producing acclaimed music isn’t just white men then I think thats a great thing. It’s not like the great tradition of British snark doesn’t live on in terrible charisma-free Vice articles.” (Scott Ramage)

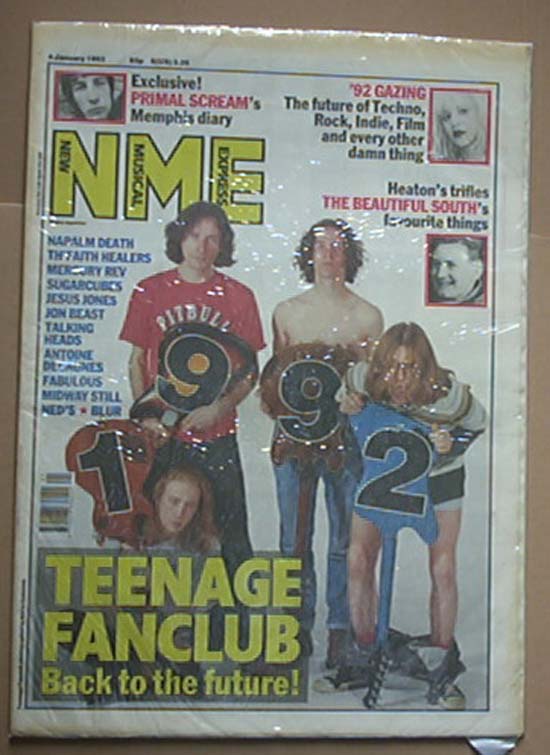

“Being a teenager in a small English town in pre-internet 1990s, NME was a lifeline. Feeling isolated and lonely much of the time, music was liter ally what kept me going, and naff as it may sound, NME was a gateway to a world where music mattered as much as it did to me. It may sound unthinkable now – but seriously, I would buy singles and albums without having heard so much as a note because I had read about them in the NME. Too many to list – but Teenage Fanclub’s Bandwagonesque is one that stands out. It opened up not just the present but also the history of music. It also featured a lot about books, films and politics which was extremely important.

ally what kept me going, and naff as it may sound, NME was a gateway to a world where music mattered as much as it did to me. It may sound unthinkable now – but seriously, I would buy singles and albums without having heard so much as a note because I had read about them in the NME. Too many to list – but Teenage Fanclub’s Bandwagonesque is one that stands out. It opened up not just the present but also the history of music. It also featured a lot about books, films and politics which was extremely important.

A while back, whilst having coffee with one of my old teachers, she told my wife that my knowledge of music at school had been ‘encyclopaedic.’ The NME must take much of the credit for that.” (Ed Jupp)

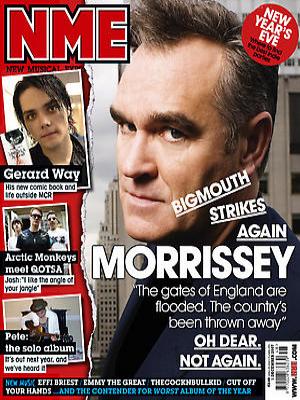

“I don’t know whether I’ve really got a favourite/least favourite memory. Obviously all the great bands I discovered through them when I was younger is good, that time they called Morrissey a racist for being racist and he tried to sue them or something but failed, that was good, but also all the times they put the Libertines on the cover despite being bad, all the other shit bands they pushed coz they were mates with the writers. Sean from DiS put something up yesterday about how it was a dream come true writing a column for them once, and fair play to him, I love DiS and stuff. But there was a band described as “spastic punk” and a caption to a photo of George Pringle (who I have no memory of but is a woman) calling her “the best looking George you’ll see” or something. And also pushing Les Incompetents who I remember being in the magazine every week at the time despite doing nothing of note. So, yeah, kind of showing all the best bits and worst bits (especially since it was published under Conor McNicholas) of the NME all at once. But then, you know, all those great bands I got into through them” (Andy Vine)

“My first memories of the NME are from the early 90s. Around the time, Seattle’s grunge scene was huge, but power centres were shifting, as Camden was fast becoming the centre of British music. The paper felt like a door into a secret, alternative adult world that was exotic, and much different from the one around me.

I was attracted to the wit and intelligence of the way it was written. The writers would alternate between challenging the reader to take music as a serious high art form, of real intellectual import, and employing childish humour.

They would often make fun of certain musicians on the scene. Every year the paper would hype up certain bands, and by the end of the year, they would be tearing most of them down, barring one or two success stories. Being an ‘NME band’ became something of a mixed blessing, in many cases.

This all happened long before the internet had taken hold, and so reading the magazine was a rite of passage, along with listening to John Peel and other specialist shows on the radio.

The NME is probably most famous for the late 70s period when journalists like Nick Kent, Charles Shaar Murray and Paul Morley were writing about punk, but this was before my time, and I knew nothing about that until much later.

For me, the NME (and similar Melody Maker) were where I obsessed over bands like the Manic Street Preachers, read about the death of Kurt Cobain, and found laugh out loud quotes from Noel Gallagher. All while riding the bus to college.

I discovered countless bands, some of which are still famous, and some of which have been largely forgotten. Young people today may have Youtube or countless blogs to choose from, but I’m grateful that it was around the time that I was coming through.

By the end of the 90s, it was obviously losing touch, and the attitude of the magazine to black music in particular began to seem antiquated.

This was at a time when grime and 2 step were emerging as vital music forms and American hip hop reached a level of prominence in popular music that brought truly into the mainstream.

The paper didn’t seem be able to authentically embrace this shift in the culture, and was instead more interested in churning out generic guitar music. It seemed to crystallise the sense that the magazine was staffed by dinosaurs.

The paper began the gradual process of terminal decline shortly after, fighting a losing battle against the rise of music blogs, which always seemed closer to the cutting edge of popular music, and had none of the baggage.

Music is infinitely different now in a variety of ways. The way it is delivered, the way word of it spreads, happens in a complex ecosphere of social media, blogs, and the real world that is music more complex than the past.

But there is a passion, and simplicity to the way the NME brought music to fans like me that I will always cherish.

Looking for the magazine on newsagent shelves, and comparing notes on which band was the next hot tip was a ritual that made music enjoyable, a private language among people in the know.” (Abbas Ali)

“For me, the NME was the very start of any kind of inkling I might have had to pursue music journalism – or even consider it in the first place. In the 1980s and ’90s, my sister [10 years my senior] was an avid reader, and would quite often leave copies lying around the house that I would sometimes sit and flick through. I had no clue as to who the bands or people they were writing about were, but the idea that writing about music in such a way was absolutely fascinating to me (I would have likely been around five – eight years old back then]. I mean, who could really forget those letters that a young Steven Morrissey sent in almost every week?! It wasn’t until my teens (roughly 14) that I began to buy my own copies. When my sister left to go to university when I was nine years old, I quickly forgot about it because it wasn’t around anymore. Because I lived in a village on the Norfolk Broads, for several years, the only way I got it was if I begged my Dad to drive me to the nearest town (which would have been Great Yarmouth) so I could get a copy from WH Smiths. But we both soon got tired of that so I plucked up the courage to ask the nice people who ran the village shop if they could order it in. And until around 2000 (when I cancelled the order), there was always one extra copy on the shelf among the rest in the tiny newspaper and magazine section. That was down to me, which I thought was both hilarious and awesome. NME broke a lot of new territory since its inception in 1952 – but it didn’t do it as easily as it might have. It had been in trouble before, but it always somehow managed to sort itself out. You have to admire that kind of tenacity! NME was the place to go if you wanted to find new and exciting music; so much so for me, that when I was writing my dissertation (for a Music Journalism degree – the only one of its kind in the whole of the UK at the time) in 2010 – I based it around New Music, and even managed to bag an interview with NME’s Mark Beaumont – a man who could have been Editor as far as I was concerned, but he was just too damn good to lose as a writer, as part of my research. It’s sad to see it finally bite the dust, but I guess it was inevitable.” (Toni Spencer)