It’s now January 2017, and for many of us life after the festive season will be returning to normal. The Christmas decorations will once again have been boxed away for the year and our houses put back to their usual state. But it is worth remembering a deeply troubling fact that we’re all too likely to shelve with the rest of the festive season.

According to figures released by housing charity Shelter late last year, there were 120,000 children facing homelessness in the UK over Christmas. In 2015, it was 100,000. And in 2014, it was 93,000. In the space of two years, the housing crisis in this country has worsened significantly, leaving more families living with the threat of homelessness. In fact, Shelter currently state that a family is made homeless in the UK every ten minutes.

But what exactly are we talking about when we talk about homelessness? As some critics of Shelter are often very quick to claim, many of those included within these statistics do in fact have a roof over their heads. Not all of these people are living on the streets.

But the statutory definition of homelessness extends to more than just sleeping rough. This isn’t some sort of dubious manipulation of definitions. This is a release of figures in line with the government’s own legislation. Homelessness in the UK, whilst most certainly including rough-sleeping, also includes (under the Housing Act 1996) anyone in temporary council accommodation, and those who have been served eviction notices. Further examples of what is considered by UK law to constitute homelessness may be found on Shelter’s website (http://england.shelter.org.uk/get_advice/homelessness/help_from_the_council_when_homeless/homelessness_are_you_homeless). But suffice it to say, that those critics who attack the figures for being misleading are very wrong.

There’s a vast amount of material out there dealing with the evolution of our housing crisis. Tracing the current problems back to Thatcherite ideals of class-mobility, where home-ownership was preached as a means to scramble from the classification of working-class status (which was made to be seen as something you’d want to scramble from). Social housing was sold off as a means to assist people in reaching this goal. Owen Jones examined these issues in greater detail within his books Chavs: The Demonisation of the Working Class and The Establishment: And How They Get Away With It. But it is becoming a widely acknowledged fact that all of this housing – some of which fell into the hands of those wishing to profit by letting it back out again – has not been replaced.

Over the years, we’ve seen ideas concerning property shift from being a basic human necessity, to being a wealth generating investment for those who hold the reigns. A profitable commodity. We’ve seen house prices rocket, thus pricing first-time buyers out of the market. We’ve seen a reverse of worker’s rights and secure contracts of employment. We’ve seen wages stagnating. We’ve seen zero-hours contracts rise in popularity. We’ve seen a brutal increase in welfare reforms, benefit sanctions and housing benefit caps. We’ve seen people fall into mortgage-repossessions, home-owners plunged into turbulence, leaving them no choice but to pick up their belongings and head gloomily back to the start of the property ladder. Begrudgingly forced into the insecurity (and financial black-hole) of renting. We’ve seen tenancies become shorter and less secure. We’ve seen landlords becoming ever more selective. We’ve seen letting agents profiting from the increasing demand in rented properties by charging grossly unjustifiably fees for their services.

In essence, there has been a swirling and noxious concoction of circumstances that have driven the homelessness figures upwards, whilst landlords and letting agents suckle greedily from the exploitative “industry” of private rentals. Those in need of housing, and affordable housing at that, are not the priority here. Their ability to generate wealth for the ones who are in control is. And if they’re not capable of powering the money-machine, they’re simply disregarded.

State-provision of housing has been, like many services within the machinery of capitalist societies, shifted to the arena of private investors and the upshot of this is that large amounts of people are suffering at the expense of personal greed. Trying to deal with this problem now in a political sense is no different to slapping sticky-plasters on the crumbling wall of an enormous dam. The issue of whether capitalism is working or not is another debate. But the issue of whether our housing system is working under a capitalist society is very much a relevant one.

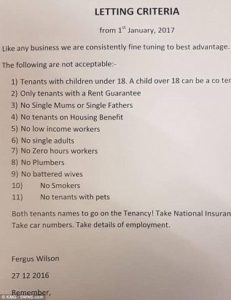

Notorious landlord Fergus Wilson was recently in the news after posting online his lettings criteria, which included eleven “rules” in connection with the letting of his property.

Whilst this list may not break the law as it currently stands, what we see here is a very clear interest in financial investment manifested by decisions of a prejudicial nature. Mr Wilson’s concern may indeed be his money, but this list demonstrates a clear lack of concern about the difficulties faced by ordinary people. And with attitudes like this becoming more and more common, where are vulnerable and needy people to turn? Where are those deemed a hindrance to landlords’ profits to turn? So much of our housing is controlled by people with similar prejudices, that the options for vulnerable and needy people are becoming more and more limited all the time. Council budgets have been reducing considerably over the years. Their obligation to house vulnerable people and people in need is costly, and so a pattern of reducing liability to assist seems to have been emerging. A freer and more relaxed approach to finding people “intentionally homeless” as a result of investigating the reasons people are evicted is one way this is being done.

I know this from direct experience. It has happened to my family. Having “upset” my last landlord for complaining in quite reasonable terms about three incidents of unlawful behaviour, we were evicted. The council’s final response to this, despite supporting our complaints fully, was that we made ourselves intentionally homeless as a result of complaining. Which means that whilst the council may agree that the landlord is behaving unlawfully, they may not always have your back when it comes to you needing some help.

This sort of thing isn’t breaking news. But it isn’t getting better either. The recent commitment of the Tories to ban letting agent fees is a very positive step in the right direction, but it isn’t enough. Despite a vacuum of contextual information about this promise, landlords were very quick to protest online about it, claiming that if they are the ones who incur letting agents’ fees, then tenants could be assured that rents would rise to compensate.

The fundamental truth of renting, is that it is very expensive. Landlords frequently defend this claim by asserting that they have debts, they make little profit from renting and other such excuses. I can’t speak for the nature of any landlord’s debts, but I will suggest that the very fact of being a property owner, and often property owners with multiple properties, is by its very definition evidence that landlords are far wealthier and in a far more powerful position than ANY tenant – who would quite likely decide, if they were able – to buy a house that’s theirs rather than plough years and years of income into a landlord’s pockets with zero return.

As there are now many more renters out there, it stands to reason that landlords not only control a lucrative market, but that they can cherry-pick from the vast supply of needy tenants and settle on the ones they feel to be the best fit for their needs. And the upshot of this is that many tenants are now in a difficult position, and the vulnerable and needy ones have increasingly fewer options. The operation of the current system renders them subservient to the landlord’s – often, although not always – intentionally oppressive whims, because to upset the landlord can so swiftly result in eviction. Had I simply tolerated my previous landlord’s unlawful practices, we might not have been evicted.

The figures presented by Shelter bother me, but they led to a mixed response from the public which really surprised me.

There were of course, people defending Shelter, and speaking sense. It would be a disservice to the public as a whole to not mention this. There were some very compassionate, understanding and decent people on that thread. But it seemed to me, that the majority of voices were slamming Shelter, slamming the figures, slamming the basis of the findings and making tenuous and pointless links to immigration figures.

The out-pouring of hate could – roughly speaking – be divided into three categories.

* If Shelter cared so much, why don’t they use the money they have to home people.

* Why don’t the parents of these 120,000 children stop neglecting their children.

* If we didn’t help immigrants so much, we’d be able to help our own kids.

Firstly, Shelter are a charity whose aim to is provide advice, assistance and to campaign for changes in the legislation for everyone’s benefit. If they wasted all the money they got through public donations, they’d very quickly have none left to help us all.

Secondly, to assume that people get evicted because the parents are neglectful is a ghastly and seriously misinformed opinion. The research is out there. One only needs look for it.

Third, the idea that refugees and immigrants are causing the housing crisis is another fundamental misunderstanding of the crisis, and also plays into the kind of increasingly popular right-wing politics that will, in the long run, do harm to this country. In defence of this argument, people were claiming that “Charity begins at home!”

A lot of people seem to genuinely believe this…that charity begins at home. And to me, this is uncharitable nonsense. Elevating the priority of a person’s needs because they are from the same country, is equal to devaluing the needs of people who are equally needy. There is nothing compassionate or charitable about that in the slightest. It suggests that you’re happy for some to suffer as long as they are from another country.

Charity does not begin at home. Charity begins in the heart, and to devalue the needs of anyone in need is not charitable, and it is not compassionate.

We should show compassion for ALL in need. 120,000 technically homeless children is appalling by any standards. And the fact that is has increased by so much in two years is very worrying indeed. What’s more worrying about it is the fact that renting in this country is so problematic, that next Christmas, it could be your children.