Forgive me for breaking with journalistic protocol here, but I am going to attempt to write a Scott Walker review without spending the opening paragraph summarising the man’s life story. Damn this feels liberating. Walker’s tale of teen idol retreating from the limelight into European Bohemia and eventually transmogrifying into the meat-beating sonic terrorist of today has rapidly become one of music’s hoariest old legends, up there with Robert Johnson selling his soul at the crossroads or Led Zeppelin abusing various forms of marine life whilst on tour – there are probably remote tribes living in the jungles of Papua New Guinea discussing the musical epiphany that was The Electrician even as I write.

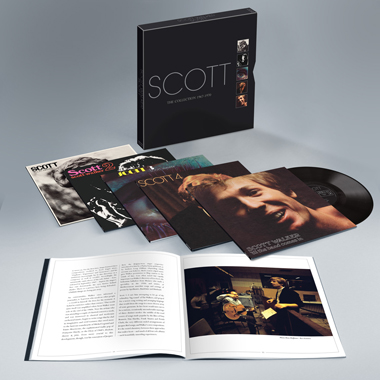

Thankfully Universal’s latest Walker reissue – a handsomely-packaged box set of his first five solo albums, ie Scotts 1-4 and ‘Til the Band Comes In – allows me to focus on the music & write about Walker’s most fertile and listener-friendly period, without having to mention Clara Mussolini or slabs of pork, topics not usually addressed by music writers but apparently de rigueur when it comes to writing about Mr Walker.

Walker’s most fertile period, but also his most misunderstood. It’s widely believed that Scott’s fans deserted him in droves when he went solo, but in fact Scott & Scott 3 reached no3 in the charts, while Scott 2 hit the no1 spot. And had Walker not stubbornly insisted on releasing Scott 4 under his own name – Noel Scott Engel – rather than his stage name, there’s no doubt it would have followed suit.

The other misconception about Walker’s early work is the over-emphasis on the influence of Jacques Brel. I came to Brel via Marc Almond and only heard Walker’s versions a few years later, and when I did I was surprised by how little of Brel’s spirit Walker had been able to capture. Brel was a captivating, versatile singer; by turns scathing, despairing, empathetic and defiant. His accompaniment varied from raucous, burlesque cabaret (listen to the original version of Jacky) to pared down accordion or piano (eg Jaures or Le Plat Pays). Yet Walker’s interpretations, well-meaning though they may have been (certainly when compared to Terry Jacks’ awful Seasons in the Sun, a cover of Brel’s Le Moribond), smother the songs’ original spirit in his smooth baritone and overblown orchestral arrangements. Listen to Brel sobbing & gasping his way through Ne Me Quitte Pas, then compare with Walker’s nonchalant croon on If You Go Away. Or compare Brel’s Amsterdam – he’s in the thick of the action, experiencing it all, and that brilliant line “Et ils pissent comme je pleure sur les femmes infideles” hits you like a punch to the stomach – with Walker’s, which is merely a vicarious, secondhand account. Only his version of the euphoric Mathilde comes close to the original, and that’s due in no small part to it being one of the most faithful English translations of a Brel song (Walker was the first singer to get hold of Mort Shuman’s Brel translations, which are as good as they come). Brel merely seems to have been a convenient name for Walker to drop in his bid to be taken seriously as an artist; he fails in capturing the brilliant Belgian’s essence.

The real pleasure to be had in listening to these reissues is in hearing Walker’s own compositions. Having honed his songwriting on impressive Walker Brothers B-sides such as After the Lights Go Out, Archangel and The Saddest Night in the World, he’s already fully-formed as a songwriter on Scott, and the first self-written song on the album – Montague Terrace in Blue – remains one of his finest achievements, its bizarre opening line (“The little clock’s stopped ticking now/We’re swallowed in the stomach room”) hinting at Walker’s later avant-garde direction, whilst that soaring chorus provides a link back to his teen idol days with the Walkers.

The two other self-penned songs (the rest of the album being made up of covers by the aforementioned Brel as well as the likes of Tim Hardin & Andre Previn) also show Walker settling into his own voice and growing in confidence. Such a Small Love, with its sparse string arrangement surging into a typically massive chorus, is another instant classic, a tale of a dead relationship told in snatches of abstract symbolism (“His shallow half-lit eyes, his rotted teeth grown on, on drunken madman nights ending up in jail”); while Always Coming Back to You is a near-perfect look back at lost love and the impossibility of moving on.

But this mix of Walker’s own work and cover versions, with the tracklisting seemingly put together at random, makes Scott a very disjointed listen, clearly the work of an artist still finding his feet and growing up in public. As is its follow-up, Scott 2, another mish-mash collection of Brel songs, schmaltzy covers of songs by Henri Mancini and Bacharach & David, and Walker’s own works. There’s little progression here, other than slightly more risqué subject matter – Jackie’s “authentic queers & phony virgins”, Next’s account of a military gangbang, The Bridge’s tales of sailors on shore leave (“The sailors stained her cobblestones/With wine & piss & death desire”).

Walker’s own writing is weaker here too. Plastic Palace People and The Bridge are amongst his most pedestrian compositions, whilst The Girls from the Streets is a laboured Brel pastiche. But he is responsible for Scott 2’s one moment of genius, The Amorous Humphrey Plugg, the tragicomic tale of a suburban everyman liberated from his humdrum existence by visits to a local brothel. “Oh, to die of kisses, ecstasies & charms/Pavements of poets will write that I died in nine angels’ arms” sings Walker, atop one of the finest musical arrangements of his entire career.

Within weeks of the album’s release, and in spite (or, knowing Scott, because of) its chart-topping success, Walker had dismissed the album as “the work of a lazy, self-indulgent man”, adding “Now the nonsense must stop, and the serious business must begin” – possibly the first sign of the fearsomely independent, forward-looking artist Walker would become.

Things do indeed get serious with Scott 3, with 10 tracks written by Walker himself, accompanied by 3 obligatory Brel covers – that the latter are the weakest songs on the album show that Walker had indeed “stopped the nonsense” and was focusing more on his own material.

And what fantastic material it is. It marks the point where Walker begins to move away from the bombastic orchestral backing and big choruses of yore, preferring instead a more restrained approach, with genius arranger Wally Stott creating intricate chamber-pop arrangements which suit Scott’s new songwriting style down to the ground. The heartbreaking Big Louise is typical of Walker’s creative rebirth here; the observational vignette of a lovelorn woman, trying to lose herself in dreams to forget her pain. “She fills the bags ‘neath her eyes with moonbeams, and cries ‘cos the world’s passed her by…Her bathrobe’s torn and tears smudge her lipstick, and the neighbours just whisper all day.” Copenhagen is near perfect, using the city as a metaphor for the awakening of love (“Copenhagen, you’re the end/Gone & made me a child again), and swelling to a quite gorgeous climax. And Two Weeks Since You’ve Gone evokes that period of desolation and confusion that follows the end of a relationship, its narrator wandering around the city in a fug of sorrow: “I could read all my sadness in faces I knew down at Kelly’s bar last Friday/And I haven’t been back since I mistook somebody for a friend…If I close my eyes for a while, will you happen to me again?”

There are a few missteps – We Came Through shows that covering Brel and trying to emulate him are two entirely different challenges, while the Dylan mannerisms of 30 Century Man just don’t suit Walker at all – but it’s a quantum leap from Scott 2 and stands as Walker’s first great artistic statement.

Scott 4, released that same year and consisting entirely of Walker’s own material, is simply a work of pure genius. The public, having searched in vain for pop songs on Scott 3 & having no idea who Noel Scott Engel was, didn’t go for it, and it didn’t even chart and was deleted soon after, but we need not concern ourselves with that.

This is bold, confident, swaggering pop from a man at the very peak of his powers, mixing the delicate ballads of Scott 3 with a new ear for a chorus. It’s an album of two halves – the first is classic solo Scott, from the rampagingly camp Bergman-the-Musical The Seventh Seal to the stunningly beautiful Boychild, via one of the great underrated Walker songs, The World’s Strongest Man, and a classic lovelorn ballad, On Your Own Again (no lyric has ever summed Walker up better than “I was so happy I didn’t feel like me”.)

The second is new ground for Walker – having dabbled with Tim Hardin covers in the past, he now throws himself headlong into a soulful country sound that, for the most part, suits him well, particularly on the brooding Duchess and the deceptively sweet Rhymes of Goodbye.

Throughout the album are hints of Walker’s experimental future – the sudden orchestral lurch of On Your Own Again, the surreal political/historical imagery of The Old Man’s Back Again, and the increasingly obtuse lyrics (“I’ve come from far from chains, from metal & stone, from makeshift designs…roaring through darkness, the night children fly” and so forth) – but Scott 4 is essentially a pop album, albeit a slightly quirky one.

And that, by conventional wisdom, is where the story normally ends. But Universal have taken the somewhat controversial step of including 1970’s divisive ‘Til the Band Comes In in this box set – divisive, because whilst some fans see it as the great lost Walker solo album, most people, including Walker himself, see it as the start of his artistic decline and the beginning of his lost years, the years of piss-poor covers albums and working men’s clubs.

Recorded under his own name and with his lyrics “censored” by co-writer Ady Semel so as not to “harm old ladies”, it’s the sound of Walker listening to the record company for once and trying to get back into the charts, with 10 Walker originals and 5 best-forgotten covers (the latter making up most of “the second side of ‘Til the Band Comes In”, as mocked by Pulp on the Walker-produced Bad Cover Version).

There’s some cringeworthy stuff here – Walker apparently chatting up the speaking clock on the appalling Time Operator, and the cod-country of Cowbells Shakin’ – and even one song, Long About Now, that doesn’t even feature Walker at all, but at the same time there’s still some evidence of Walker’s brilliance on display. Joe is the poignant tale of a dying, forgotten old man (“They say towards the end/You hardly left your shabby room”) set to a jazzy early-Tom Waits arrangement; The War is Over recalls the delicate chamber pop of Scott 3; and the gay Dear John letter of Thanks for Chicago Mr James is simply one of the best things he ever did, the line “I’ll move as I began, through fields without a plan” possibly summing up the aimlessness of this stage of his career. Otherwise, you can hear why Walker was quick to disown the record and why it lay forgotten for 25 years.

The box set itself is nicely packaged with the original artwork and accompanying booklet, though it’s hard to imagine who it’s aimed at – Walker devotees already have all this stuff (which has been remastered before), and he’s hardly spent his recent years winning over hordes of new fans. The 2006 Five Easy Pieces box set, which thematically compiles his solo work, is probably a better introduction for the curious. As for Scott: The Collection, it’s a wonderful excuse to immerse yourself once more in this superficially smooth baroque pop and hear a man going from nervous boyband escapee to master of his craft. As Julian Cope described him, truly a Godlike Genius.