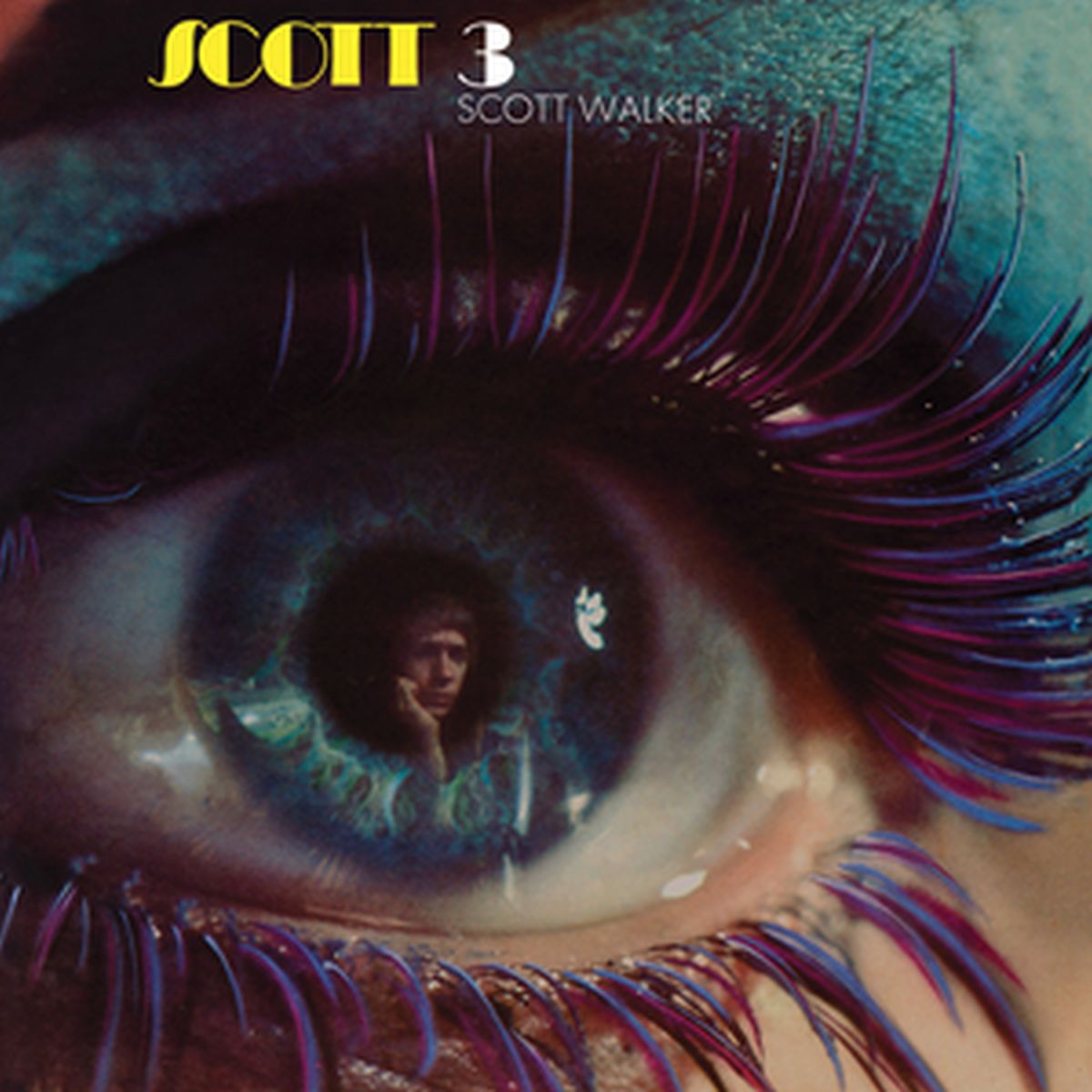

“It’s the work of a lazy, self-indulgent man. Now the nonsense must stop, and the serious business must begin.” So wrote Scott Walker in the sleevenotes for Scott 2. By the end of the 1960s, having already transitioned from Walker Brothers pop pin-up to producing pompy orchestrated Jacques Brel interpretations as a solo artist, the follow up, Scott 3, marked the next departure in his career. While writing MOR ballads for his TV show to pay the bills, Scott was given the freedom to record his new long player, which became the vehicle for his more artistic compositions. So aside from the three Brel covers relegated to the end of the album, all of the songs are Walker originals.

Thus Scott 3 is the exquisitely drawn sound of a burgeoning Scott Walker as baroque songwriter artistic visionary, a luxurious body of work; it’s a sound that would reverberate upon albums like Climate of the Hunter in latter decades and influence the likes of Marc Almond, Jarvis Cocker and Brett Anderson to name a few. Eschewing the more bombastic string led melodrama of Scott 2, its follow-up Scott 3 marked the full emergence of his songwriting talent and draped it in a suite of lavish string arrangements provided by Wally Stott.

It’s there in Scott’s unsettling, world-weary miniature symphonies that examine characters with a poetic fine detail, given life by Walker’s by now cavernous sounding yet weighty baritone. The majesty of opener ‘It’s Raining Today‘ is a grand, sumptuous beginning that hoves into view upon a bed of shimmering orchestration, grasping for fleeting moments in time (‘the train window girl’) like raindrops that “descend on [his] windowpane,” setting the scene of the urban landscape teaming with the dispossessed and outcast, and frames it in an existential heartbreak and regret.

This is followed by the elegantly romantic ‘Copenhagen’ where the city’s vivid imagery becomes a metaphor for heart-leaping first flush of love, as Scott’s vocals arc above this delightful suite of strings. A symbol for his deep love of European cities and culture, it’s also a surprising tracklist from an album that is pitted with little surprises and confounds throughout.

‘Voices from a photograph/Laughed from your wall/Screamed through your dreams’ croons Scott, sinisterly tip-toeing over strings that stab, on the startlingly brilliant ‘Rosemary.’ Each striking couplet initially endears then stings in the tail as he paints a heartbreaking narrative of a lonely young woman. It’s a gorgeous track which confirmed that not only is Walker a great singer, he’s also in possession of a fearless poet’s eye. It’s matched by the fantastic ‘Big Louise’, which is about a transvestite whose life begins to embody the cruel passage of time ( “She fills the bags ‘neath her eyes / With the moonbeams / And cries ‘cause the world’s passed her by”), these songs were the sound of a daring pop artist exploring taboo subject matter in 1969.

Shifting gears, ‘We Came Through’ gallops like a grand cavalry on an indestructible Western soundtrack, all gunfire and horses hooves, juxtaposing the orchestral grandeur with the squalid gutters of mankind. All too tantalizingly brief, gorgeous moments that clock in at under two minutes, are scattered throughout from the fluttering sweep of harps and strings on the delicately meditative ‘Butterfly.’ To the incongruous, almost quasi folkish strum of ’30th Century Man’, Scott’s voice is let free from its perfect pitch to lip curling Dylan-like, faintly ridiculous, almost country tinged playfulness. Scott sketches out, at times, surreal self revealing imagery, contrasting the dwarf and the giant: he stylishly dismisses current persona and the farce of his fleeting fame that he reckons he could freeze for “a hundred years or so” in some vein attempt to preserve its freshness. “I could read all my sadness in faces I knew/Down at Kelly’s bar last Friday” swoons Scott, returning to the recurring theme of loss on the effortless majesty of ‘Two Weeks Since You’ve Gone’, Scott staggering around drunk with pain and longing; it echoes with a rejection he may have experienced from not just lovers but perhaps fame itself.

Some could mistake Scott 3 for easy listening, comparing it to the work of Bacharach, Andy Williams or even Sinatra, but this would be simplistic and trite because Scott 3 is a densely layered classic, ripe with knowing and self exploration. Scott imbues each of his characters into a deep well of evocative emotion and daubs them with a musical sophistication that far outstrips any of his contemporaries. Fearlessly and boldly, he made it a forward looking record, a portrait of an emerging artist, whose commercial ill fortune would be contrasted by its enduring influence alongside its follow up Scott 4 (where he expanded his palette once again to create his first all original album). Scott 3 stands as one of his most visionary, bold, at times varied yet thematically cohesive early works and it still stands the weathers of passing of time.