The UK Music organisation recently published ‘Wish You Were Here 2016‘, a report on live music’s contribution to the UK economy in 2015. The main reason for doing so, as stated by UK Live Music Group chairman Paul Latham, is to make national, but especially local, government take live music’s economic worth more seriously. The relatively new organisation Music Venue Trust, founded in 2014 to “protect UK live music networks” also contributed to the report. In summary, the report breaks down UK live music tourism regionally and, for the first time, includes data on grassroots music venues.

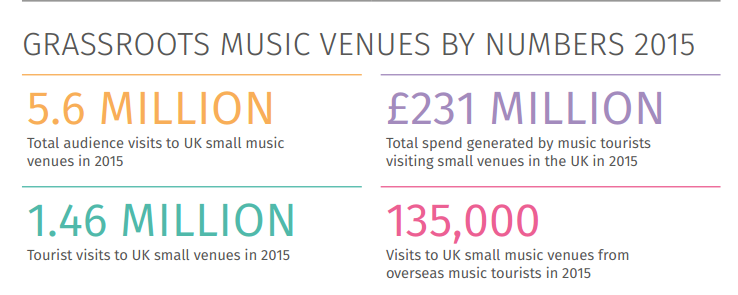

The statistics on live music and especially live music tourism are impressive to say the least. In 2015, the total live music audience amounted to 27.7 million people. Of this figure, 38% were tourists (up by 13% from 2014) who in total contributed a whopping £2.3 billion to the UK economy. For small venues, attendance was at 5.6 million, with music tourists generating £231 million from this to the country’s economy.

Despite the optimistic figures though, the report rightly criticises the government’s contradictory position on the value of music with one example being that the new compulsory English baccalaureate announced last year excludes any creative subjects. Academia still rules over whether a pupil is considered capable, at least while the Tories are in power. This adds to the elite nature of much of the live music accounted for in the report.

For example, the report may boast that this country is home to the three biggest-selling arenas in the world (Glasgow’s SSE Arena, Manchester Arena and London’s 02 Arena), but their market-based pricing system often means charging fans extortionate ticket prices. Organisations like Live Nation and AEG monopolising mainstream live music further contribute to this. The people behind this surely don’t really care for music (and making music available to as many people as possible) but for business. If live shows of the biggest acts aren’t accessible to all, then how is this such an economic success? On top of the slow increase in the ‘poshification of pop’, it seems the biggest live music events are also becoming only available to those with a certain amount of financial backing.

Another problem with this report is that it’s unclear about how it’s measuring its data. They state grassroots venues are ones with less than 1500 capacity though more informal venues may have been left out of this calculation. Whether or not the grassroots venues they fail to be more specific about include the recent surge of ‘DIY’ venues, it’s evident that an increasing chunk of live music is driven by their emergence. Sheffield’s Audacious Art Experiment, Nottingham’s JT Soar, Leeds’ Wharf Chambers, Manchester’s Partisan Collective and DIY Space For London are just a few of these community-driven, not-for-profit places. Such self-sustaining entities are hard to measure by an economy fixated on growth. These are the kinds of places whose events aren’t listed on any box offices, who maintain a strictly all-ages policy, who tell their attendees ‘no one turned away for lack of funds’, who support the kinds of artists not intending to make a living off their music like headliners in arenas do. This is the kind of live music that’s becoming more popular but its informal nature makes it harder to translate into statistics for a government report. It should also be noted that these venues are the ones most under threat from closing.

On a highly relevant note, leaving the EU could only change the UK’s music economy for the worse. In a thorough investigation by Pitchfork, they found that all aspects of the music industry have worries on how a Brexit would hit them. For UK musicians, touring Europe would likely lead to a bit of a visa nightmare (the USA is rarely toured by UK acts for this very reason), a loss of connections especially important to DIY artists and a general stifling of musicians’ ability to reach others. On the industry side, UK labels, festivals, promoters and music retail outlets would similarly suffer from a loss of audience, as well as a struggle to compete in other international markets and possibly losing their voice on issues such as copyright. Since almost 40% of live music tourists last year were from overseas, many presumably from Europe, it couldn’t really be more obvious how leaving the EU could give the industry a considerable setback. Liveurope coordinator Fabien Miclet even calls the UK the “beating heart of the European music scene.”

It goes without saying that live music is a true cornerstone of cultural and social life in this country. Its economic worth is invaluable, and grassroots venues should be particularly supported and protected in the interest of making live music open to as many people as possible. UK Music’s recent report may not give us the whole story but it’s at least a start. Encouraging more people to care about live music and its effects is an essential way to preserve it.