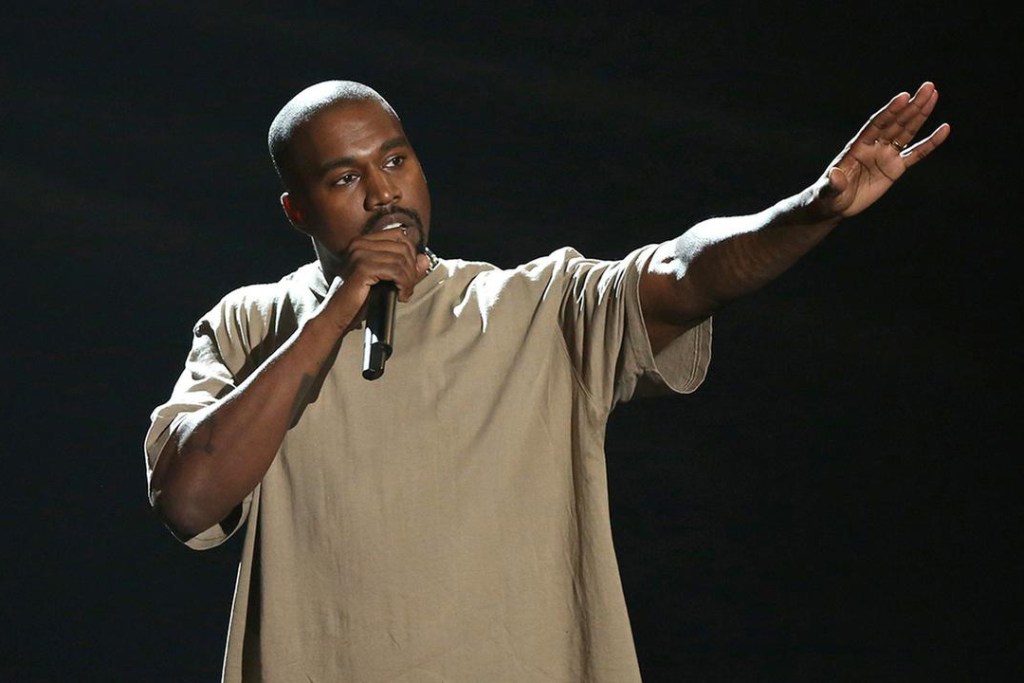

The release of Kanye West‘s new album, The Life of Pablo, has been something of a clusterfuck. Everything, from its title to its track-list to its musical and lyrical content, has been revised multiple times, and quite a few of those revisions occurred after its official release date (14 February).

It would be easy to chalk this all up to a simple lack of planning, but many commentators have found a different angle on the whole thing:

It was bad enough when Taylor Swift offered us two different versions of 1989 – regular and deluxe – then released deluxe-edition-only track New Romantics as a single, thereby revealing that the deluxe version was the real one and that us poor suckers who bought the standard CD only got 81% of the full story. But this Life of Pablo stuff is a breed of chaos that I’m not sure I can even process; that we may eventually end up with a hundred different versions of this LP, none of them truly definitive, is an intriguing thought, but how can I properly appreciate an album if it won’t sit still long enough for me to even weigh it up? It usually takes me a good few listens to really get a feel for an album, and I suspect that this constant state of flux would keep me permanently locked out of the experience. If an artist I actually liked were to pull this stunt, my primary reactions would probably be disappointment and a feeling of alienation.

It gives Kanye’s fans a deeper insight into his creative process.

“Think of how we understand pop music titans like Dylan or Prince. Over time, more demos and alternate versions and live versions get released — officially or not — and our understanding of their process deepens. Given the speed and porousness of the Internet era, we may soon be able to assess and comprehend Mr. West in much the same way. Albums that seem to be complete will only get less so. Songs that sound fixed in stone will be revealed to be the product of much trial and error. The process will be laid bare, as fascinating as the end result.”

Okay, sure – it is sometimes cool to hear the rough sketches that begat the fully-formed bangerz we know and love. But it’s eminently possible to share those sketches with listeners without compromising the sanctity (ugh) of the album as a single, standalone piece. Tindersticks handled this well with the 2004 remaster of their self-titled debut; the reissued version came with a bonus disc containing twelve demo tracks, most of which were early versions of key tracks from Tindersticks itself. This package gave fans a sneaky peek at the flesh and bones of their favourite songs whilst still allowing them to experience the original work in full, sans tampering (remastering don’t count because this undertaking, generally speaking, doesn’t change the actual content of the album).

Or, if ‘bonus disc’ is too humdrum a treat for your listeners, why not do what PJ Harvey did last year and just let people watch you while you’re in the recording studio?

It allows Kanye to make continuous improvements, even after the album has been released.

“Two days before Mr. West played Pablo for the world at a Feb 11 fashion show at Madison Square Garden, he held a listening session for friends, family and representatives of his record label. The next day, a Reddit user began a thread titled, “Rumor: Kanye West is going to diss Taylor Swift on his new album.” The post went on to detail the opening lines from Famous: ‘I feel like Taylor Swift still owe me sex/ Why? I made that bitch famous.'”

It means that the album constantly remains fresh.

It means that no single edition or reissue of the album can be held up as any more ‘definitive’ than any other.

Now here’s the one benefit of this model that I can really get behind. I hate it when I buy an album and, less than a year later, out comes the ‘Special Edition’ with more extras and incentives and inexplicable rewards for the people who were smart enough not to buy the record when it first came out. It always feels like a bit of a middle finger to the fans who bothered to go to the shops on release day – at least Taylor Swift was gallant enough to release 1989 (Deluxe) at the same time as the standard version, giving us the choice right off the bat rather than forcing us to re-buy or miss out further down the line.

So there, finally, is a harbour at which I may be willing to board this ship: if Kanye West’s model of constant change eradicates those dickweedy, cash-grab, come-on-at-least-wait-a-couple-of-years re-releases that seemingly aim to discourage people from buying their favourite band’s new album right away, then perhaps I’ll rethink my position on this matter.

For now, though, it all just strikes me as kind of cowardly. One of the hardest parts of any artistic endeavour is the part where you step back and decide that, yes, this is complete, this is An Art that I’m happy to share with the world. By coming back and tinkering with The Life of Pablo every time he thinks of something else he wants to change, Kanye West is unburdening himself of his duty to take that step, and I’ve no real interest in listening to his “unfinished masterpiece” until he starts acting like it’s actually ready.