The No Wave scene of ‘70s New York has been all but relegated to a footnote in the history of outsider pop. The ramshackle grooves and rudimentary musicianship is punk at its core, but the scene’s aims went beyond the recycled tropes of rock into a sense of artfulness and originality. Light In The Attic, a cult label specialising in reissues of lost, forgotten and maligned music across all genres, have done sterling work in their attempts to redress the balance of canon formation by unearthing outlier gems, and following last year’s reissue of Lizzy Mercier Descloux’s debut Press Color comes four remastered albums from the French No Wave singer’s later career.

Descloux was a cross-genre stylistic renegade, drawing on world music, post-punk, jazz and dub reggae, her catalogue exploring a world of sound. These albums were recorded all over the world, from the Bahamas to South Africa, and the lyrics include English and French, but Descloux’s vision seems beyond any corner of the world, untethered to convention and expectation. The four albums (and last year’s reissued debut) are varied and distinct, but there’s certain features that bind them together. The most obvious is Descloux’s voice: a girlish, breathy mix of purrs, gasps, yelps and snarls, expressive and energetic in its commandment. Descloux is not a natural master of vocals, straining and missing notes at times, but her vocals are rich in character and personality. It’s a thrilling instrument that most obviously recalls The Slits’ Ari Up, but also Neneh Cherry at her feistiest, Grace Jones at her most bracing, even Madonna at her most playful.

The other thread common to these albums is Descloux’s approach to rhythm. Afrobeat influences loom heavily, particularly on the drums and basslines, while the melodies and structures range across the spectrum of world music. Descloux may have travelled the world absorbing ideas, but it’s a fragmented approach, a melting pot of disparate styles and ideas than full immersion in specific subculture. The more cynical might see cultural tourism and appropriation, but Descloux treats her influences with respect, presenting them as a natural directions for her music to take, rather than any sense of exotic cosplay.

1981’s Mambo Nassau is the earliest of these albums, and feels the most primitive. With its simplistic basslines, flailing drums, unsophisticated sound palette and Descloux’s undeveloped vocals, it’s the work of an amateur auteur. Mambo Nassau feels minimal and spacious in its post-punk grooves, recalling !!! and Out Hud, a sense of deliberately angular funk running through its disco strut. There are throwaway moments – skit ‘Milk Sheik’ runs under a minute, and its merry-go-round oompah march jars – but it suggests a myriad of directions Descloux could have taken.

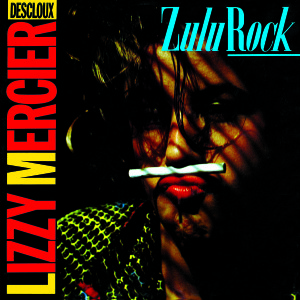

Zulu Rock follows, and it’s easily the stand-out Descloux album. The arrangements are richer, with organs, accordions, even African choirs providing backing vocals. The melodies are adventurous yet instinctive, while rich brass and steel guitars create an atmosphere of exotic luxury. Descloux’s voice is at its most charismatic, falling up and down octaves as the music struggles to keep up with her frantic delivery. At times it can feel a little overpowering, echoing the excess of Kate Bush’s The Red Shoes, but for the majority it sits at the intersection of Talking Heads and Paul Simon. In any case, Descloux sounds like she’s having too fun much to care, and on tracks like the irresistible ‘Wakwazulu Kwzizulu Rock’, it’s impossible to not get swept up in the joy of it.

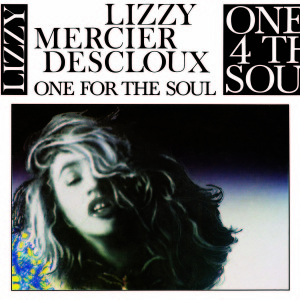

The album spawned the accidental hit ‘Mais Ou Sont Passees Les Gazelles?’ and thrust Descloux into the spotlight, creating pressure to follow-up with another commercial success. The resulting album, One For The Soul, sounds polished and glossy in a way that her prior releases could never. But it takes the wrong approach to what makes Descloux such a captivating performer, downplaying her idiosyncrasies with refinement and almost a sense of tastefulness. It doesn’t help that One For The Soul contains the most underwritten songs of her career. Acclaimed jazz trumpeter Chet Baker guests, but it’s not enough to save it from feeling like a misdirection. There’s still plenty to recommend about it, but as a follow-up to Zulu Rock it feels like a missed opportunity.

The final album of Descloux’s career, Suspense, isn’t quite a return to form, but it’s a strong improvement on its predecessor. It’s the one album of Descloux’s where the role of the studio becomes obvious, with manipulated sounds and audio trickery expanding her range as a performer and songwriter. Again, it feels tame by comparison to her earlier career, but there’s a wealth of potential in the ideas it explores.

The record label didn’t agree: Suspense failed to provide a hit and Descloux retreated from music to focus on painting and writing. Descloux passed away in 2004, aged 47, following a year-long battle with cancer. To die so young is a tragedy, and it is compounded by the fact that, for the majority of her life, her talent and vision was somewhat maligned. These reissues are an act of retroactive justice for an unparalleled creative whose ability to investigate, interpret and interpolate a world of sound was matched by nobody else. Descloux’s spirit lives on: in art-rock heroes like Vampire Weekend, pop provocateurs such as MIA, singular visionaries like Roisin Murphy. These reissues are a fitting tribute, but her subtle yet vital influence on pop culture is her legacy.