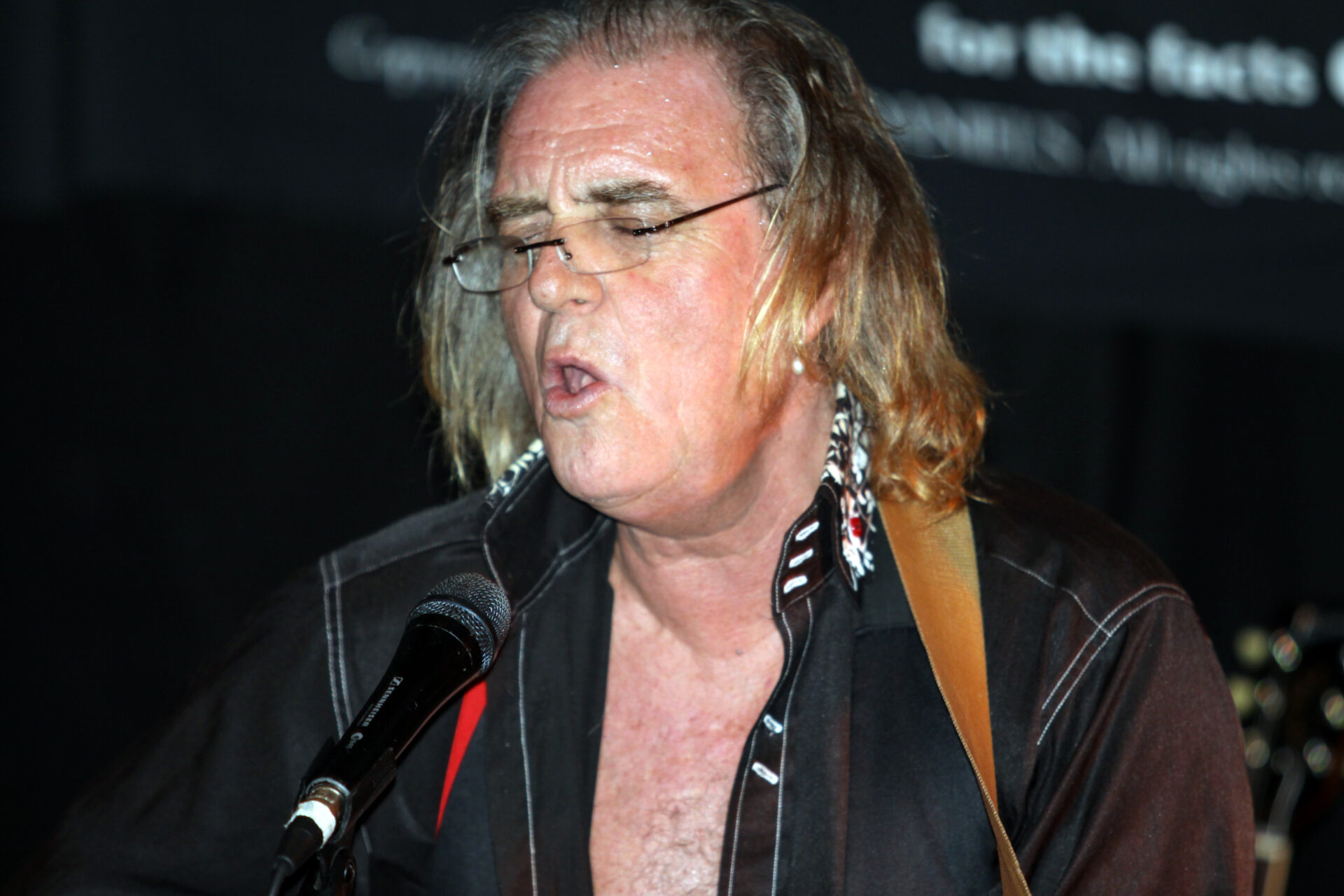

“There are only three things happening in London: The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Terry Reid.” Thus spoke Aretha Franklin in 1968 after catching Reid in the capital’s Revolver Club. But whilst the two bands then highlighted by Lady Soul went on to attain musical immortality, the man from Huntingdon in Cambridgeshire with one of the greatest rock/soul voices this country has ever known saw his career drift into relative obscurity.

“There are only three things happening in London: The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Terry Reid.” Thus spoke Aretha Franklin in 1968 after catching Reid in the capital’s Revolver Club. But whilst the two bands then highlighted by Lady Soul went on to attain musical immortality, the man from Huntingdon in Cambridgeshire with one of the greatest rock/soul voices this country has ever known saw his career drift into relative obscurity.

A handful of records followed – both 1973’s River and Seed of Memory from three years later can rightly be described as classics – but the fact that Terry Reid’s last studio offering The Driver was released in 1991 gives some indication as to his general lack of productivity. Yet he has not been entirely inactive and for the past 10 years he has routinely returned to this country from his exiled home in the Californian desert to treat us to his still quite supreme artistry.

Tonight we are again blessed to be able to spend time in Terry Reid’s company, time which is as much about his storytelling as it is about his music. Before a chord has even been struck, he pays handsome tribute to B.B. King who had sadly passed away earlier on in the day, recalling a time with some lascivious relish of when the great American bluesman had introduced him to a young Donna Summer. Reid is not only a wonderful raconteur – even if we have heard variants on these stories many times before – he is also a shameless name-dropper. Before the evening is out he has referenced most everyone from Otis Redding to Keith Richards; Robert Plant to Graham Nash (who produced Seed of Memory); to Brian, Carl and Dennis Wilson (before his incredibly loose yet supremely heartfelt rendition of ‘Don’t Worry Baby’), all of whom he seems to know (or have known) on a personal basis.

is as much about his storytelling as it is about his music. Before a chord has even been struck, he pays handsome tribute to B.B. King who had sadly passed away earlier on in the day, recalling a time with some lascivious relish of when the great American bluesman had introduced him to a young Donna Summer. Reid is not only a wonderful raconteur – even if we have heard variants on these stories many times before – he is also a shameless name-dropper. Before the evening is out he has referenced most everyone from Otis Redding to Keith Richards; Robert Plant to Graham Nash (who produced Seed of Memory); to Brian, Carl and Dennis Wilson (before his incredibly loose yet supremely heartfelt rendition of ‘Don’t Worry Baby’), all of whom he seems to know (or have known) on a personal basis.

Terry Reid is the musician’s musician and Mick Taylor is another person referred to as one of his close friends, something that reminds me of that time in August 2007 when the former Stones’ guitarist joined Reid onstage at the Rhythm Festival in Bedfordshire and the two men tore through Ray Charles’ ‘I’ve Got News For You’ in a euphoric burst of music which to this very day remains one of the single most incredible pieces of live musical entertainment I have ever had the pleasure of experiencing.

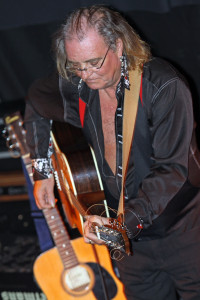

Tonight could never hope to come anywhere near to that astonishing performance, but it is not without its own individual highlights. Reid draws his now almost obligatory quartet of songs from Seed of Memory – the entire first side of the original vinyl album – ‘Faith To Arise’; the record’s imperious anti-war title track with which he routinely closes his set; ‘Brave Awakening’, which is added an even greater poignancy with the presence in the audience of members of his family; and ‘To Be Treated Rite.’ But it is on the one solitary song he plays from River – the record’s exquisite title track – where Reid truly showcases the excellence of his own material as he fuses jazz, blues and folk into a glorious amalgam of hypnotic abandon. The song takes a long, languid path as it slowly ebbs into ‘July’ (from his second, eponymous album) before effortlessly flowing right back into ‘River’ itself.

Yet for all the timeless appeal of his own back catalogue it is on the songs of others where Terry Reid truly excels. American country singer Marty Robbins’ ‘Bend in the River’ – a staple of his set for the past few years now – somehow sounds even richer this evening. And more recent additions to his repertoire – ‘I Can’t Change It’ and ‘Scarlet Ribbons (For Her Hair)’ – reinforce Reid’s impeccable ear and unerring ability as a musical interpreter. The former is a song written by Frankie Miller and first appeared on the great Glaswegian singer-songwriter’s debut album Once In A Blue Moon. Tonight it serves as a tearful reminder of Miller – another of rock music’s nearly-forgotten-men – who was sadly stricken by a brain haemorrhage in 1994, something from which he has never fully recovered. And the latter is taken from the Great American Songbook and shows Reid’s innate grasp of timing as he sings just behind the beat, in a reading of the song that owes more to the American crooner Jimmie Rodgers than it ever does Harry Belafonte (who first charted with the song in 1956.)

Yet for all the timeless appeal of his own back catalogue it is on the songs of others where Terry Reid truly excels. American country singer Marty Robbins’ ‘Bend in the River’ – a staple of his set for the past few years now – somehow sounds even richer this evening. And more recent additions to his repertoire – ‘I Can’t Change It’ and ‘Scarlet Ribbons (For Her Hair)’ – reinforce Reid’s impeccable ear and unerring ability as a musical interpreter. The former is a song written by Frankie Miller and first appeared on the great Glaswegian singer-songwriter’s debut album Once In A Blue Moon. Tonight it serves as a tearful reminder of Miller – another of rock music’s nearly-forgotten-men – who was sadly stricken by a brain haemorrhage in 1994, something from which he has never fully recovered. And the latter is taken from the Great American Songbook and shows Reid’s innate grasp of timing as he sings just behind the beat, in a reading of the song that owes more to the American crooner Jimmie Rodgers than it ever does Harry Belafonte (who first charted with the song in 1956.)

For a concert that stretches to way over the two-hour mark, it probably only offers us something like a dozen or so songs. Much like Terry Reid’s career itself it is a long, rambling, uneven and occasionally directionless affair but one that is punctuated by several moments of sheer, evocative brilliance.

Photos and video credit: Simon Godley