As we approach the tenth anniversary of legendary broadcaster John Peel‘s death, Horse Party guitarist Seymour Quigley tells us what John meant to him:

People never ask me about John Peel, because I never talk about him. We weren’t related, and we weren’t close friends; I can’t tell you what motivated him, what kind of a husband or father he was, or how many sugars he had in his tea. But the simple fact is that John Peel, who passed away ten years ago this month, saved my life.

When I was 21 I formed a band. We were called Miss Black America, and we were grotty, irate indie-punks. We weren’t particularly good in the early days: Half the band were still at school, we had little in common beyond all liking The Stone Roses, and I, an anorexic, self-destructive, bleakly depressive, periodically insufferable rent-a-punk, had a habit of drinking to the point of collapse and singing like ants were crawling up my anus. Our first EP sounded dreadful, like it was being played through a transistor radio in a giant metal dustbin, but we sent a copy to John Peel’s home address and to our bemusement and delight, he not only played it on Radio One, but invited us – a bunch of rotten misanthropes from a backwater nowhere – to come and do a session (we ended up doing four Peel Sessions – two at Maida Vale, two live – a fact which absolutely floors me to this day).

John’s patronage meant that other people started taking us seriously, and before we knew what was happening we were signed to an indie label, doing radio sessions galore (Steve Lamacq on Radio One, 6music’s Tom Robinson, XFM’s John Kennedy, Virgin Radio), the music press were bigging us up as “The Next Big Thing” (ha!) and we were touring, and drinking, relentlessly. It couldn’t last – and it didn’t – but by the time that band split up, seven acrimonious, boozy, maddening yet oddly glorious years later, everything about my life had changed. Through our DIY exploits, I had become a musician, record producer, fanzine writer, radio DJ and gig promoter; I met some amazing people, many of whom I’m still friends with to this day; and one night in February 2003, at Tunbridge Wells Forum, at the end of a 30-date tour, I met my future wife, Kate, the woman who made me want to carry on living, and who is now the mother of our beautiful son. Kate had found a copy of our most popular single in her local record store and liked it enough to come to a gig; a single that existed because the label had heard our first John Peel session and liked it enough to sign us. I am still alive because of John Peel; my son exists because of John Peel. Judaism teaches that “He who saves a single life saves the World entire”. How many lives did John Peel save?

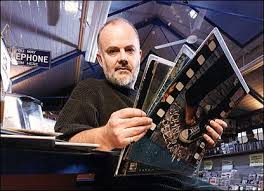

I met John a few of times and he was lovely. He used to turn up at gigs with his wife, Sheila, and we’d talk about ordinary stuff – family horrors, house prices, the weekly shop. Sometimes I’d bump into him outside Pizza Hut in Bury St Edmunds town centre and we’d have a little chat. That nice guy you heard on the radio was exactly the same guy you met walking down the street. My bemusement at the fact that he’d ever played my band at all was explained in a story told to me by Greg McDonald, frontman with fellow Peel-endorsed Bury band The Dawn Parade. Whilst setting up for their Maida Vale session, the BBC postman had delivered four sacks, bulging with CDs, tapes and vinyl, all addressed to John Peel. Greg sidled up to John and suggested that most of the bag’s contents would probably go unheard. On the contrary, replied John: Every single envelope would be opened and every single record would be listened to, because “each envelope contains somebody’s dreams”.

This is why John Peel was the most important and most celebrated radio DJ in broadcasting history: He understood the value of all recorded music, appreciated the hours, days, months and years of toil and sweat that went into every release, particularly with DIY acts and labels who went out on a limb to do something new and exciting. Rather than cushioning himself behind an impenetrable wall of producers, you could send something directly to his house and if he liked it, he’d play it on the radio, regardless of genre. It was that simple. The only context that mattered to John was the universe each record occupied in itself; he understood implicitly that music can only be judged on its own terms, not based on transient and whimsical popular trends. He excluded nothing, and loved everything. Far from the snobby curmudgeon his despicable Radio One peers (Jimmy Savile, Dave Lee Travis) presumed him to be, his radio shows were a beacon of inclusivity, the sound of purest joy.

People never ask me about John Peel, because I never talk about him. I never talk about him because he saved my life, and 10 years later, all I can think to say amounts to, “Thank you.”