Drako Oho Zaraharzar can remember modelling for Salvador Dali and hanging out with The Stones. But he can’t remember yesterday. Filmed over four years, The Man Whose Mind Exploded attempts to understand and accept the worldview of someone with serious brain damage, and it resonates for anyone who’s tried to care for someone who may not be great at caring for themselves. Following a severe head injury, Drako Zaraharzar suffers from terrible memory loss; he can access memories from before his accident, but can’t imprint new ones. As he puts it, “the recording machine in my head doesn’t work”. Consequently, and as an antidote to depression, he chose to live “completely in the now” and in accordance with the bizarre mottos delivered to him whilst in a coma. Toby Amies starts off making a film exploring Drako’s lurid and exotic backstory including work with Dali, Warhol’s Factory, Les Folies Bergère, and Derek Jarman. But frighteningly soon a line is crossed, and the documentary maker becomes carer. Drako’s way of life and the extraordinary collage of notes to self and erotic art he lives in [the source of the film’s title] threatens his health. What follows is unique, eccentric, funny and moving documentary about the relationship between two men, one who’s trying to make a film about the other, who’s existing in what appears to be a separate reality.

I spoke to the director Toby Amies [or Toby Jug as Drako called him] about the utterly unique and heart warming Drako, and the making of a very special film.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

1. How did you first meet Drako?

A friend of mine had been given some money from the Arts Council to make a silent film in front of which his band Oddfellows Casino could perform. And he suggested we use to Drako. I’d already seen Drako in Kemptown the neighbourhood of Brighton I used to live in, and I’d been fascinated by him from the first moment he cycled past me in a cape!

2.What drew you to making a documentary about him?

Initially it was his exotic appearance, and biography – one that included work with Salvador Dali and Derek Jarman. But increasingly it was his personality and his sense of humour,

I thought I was going to make a film about his past but in fact what I ended up filming was our relationship. Now that I have some perspective I realise that that is what interests me more, putting something on screen that is vivid and vibrant – alive, rather than just describing something that happened in the past.tThere is too much of that re-telling of history in documentary film because I think it is easier to fund. If you can present people with pre-existing story it will give your backers more confidence. Because our film is independent we were able to take a leap into the unknown, that is much more interesting to me, the finding of meaning through questions rather than just adding pictures to a magazine article.

3.To me the documentary is as much about memory loss and dementia as it about Drako himself, delicate topics to cover. What was very life affirming though is that although you cared for him as a character, there was very little pity involved. Was this a conscious decision?

Pity is not really of use to anyone is it? I am interested in the distinction between sympathy and empathy. Sympathy is presented as a positive emotion/dynamic when in fact it’s very much a hierarchical one – you have to feel yourself in a more positive position than the target of your sympathy to experience it, whereas empathy is more about recognising shared humanity. Loss, failure, fucking up, those are hard things to accommodate, and those are the things I am keen to find ways to cope with through the process of making films and taking chances. Also it was important for me to share my sense that Drako’s point of view was just as significant as anyone else’s even though I knew him to be coping with serious brain damage. When we were editing the film it was very important for us never to objectify Drako, but to keep the audience in a subjective relationship with him the whole way through. That way we got to give you a sense of how life affirming and frustrating having a friendship with Drako was. Also autonomy is important to all of us, and part of the process for me was understanding how Drako perceived his own autonomy, and how he defined it , which often was in opposition to what those of us who cared for him wanted.

4. It was obvious as the film developed that you were more then just ‘the film maker’ You actually became Drako’s carer to a certain extent, how did this personally affect you?

Well it was difficult. And I still have very arbitrary feelings about the whole process. I’m not sure I was a very good carer and I certainly didn’t formally take on the role so it was hard to know where my responsibilities were. Whilst I was making the film my sister was battling with acute type one diabetes, a struggle that she lost. And in both my conversations with her and Drako the most important thing was that [whether or not I thought they were looking after themselves in the most appropriate way], their autonomy was respected, no matter the consequence.

5. He was not an unloved man, far from it, but yet because of his daily memory loss, he seemed to live quite a lonely existence. As one particular psychologist suggested, when someone is overly positive all the time, this could be a sign of deep rooted depression never dealt with. Do you think Drako ever fully accepted what had happened to him, and fought his demons?

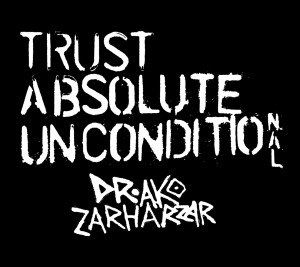

Whether or not it was a conscious process, I felt that Drako had designed/accepted the most appropriate response to his condition and the associated depression, for him. I can’t speak for Drako but I imagine if you are faced with that amount of brain damage, you have no choice but to accept it. That said he mentions 10 years of depression in the film. And the final conversation with Mim is about the degree to which he turned a question about his fate and life into an answer for himself. His beautifully simple philosophy of TRUST ABSOLUTE UNCONDITIONAL goes from question to statement. Ultimately aren’t we all hypnotising ourselves to enjoy the now in the face of our inevitable doom? Cheerfully.

6. TRUST ABSOLUTE UNCONDITIONAL – explain Drako’s mantra to me?

With the mantra that simple so much is open to individual interpretation. Personally I saw it as an expression of Drako’s faith in the fundamental benevolence of the universe. Without a useful short term memory he chose to throw himself upon the mercy of his environment and the people around him, trusting completely that what was in store for him was good, or at least meant to be. Both through the experience of getting older but especially working with Drako I have learned the benefit of being accepting of far more than I used to be. I can change some things, but I can’t change EVERYthing. Drak’s philosophy provides a basis for that process.

7. Without giving too much away, the ending did surprise me. This said a lot about care in the community and how we have lost that community spirit of caring for each other…what do you think has gone wrong in our society, and the lack of care we show our elderly and vulnerable?

I’m not sure I necessarily look at it in terms of something having gone wrong with our society. Broadly speaking my sense is that things now are better than they were. And I am reluctant to to look at things in terms of the good old days versus the bad present. Though it’s clear that there could be better care for the elderly and infirm. I am sure a form of care would have been available to Drako, but it was also clear, that he didn’t want it. Drako had made a decision to cope with his condition, independently, and those of us who were in his wider circle of care, chose to respect that. The film documents part of that process, both in terms of those times when we attempted some form of intervention, and some of the discussions and associated emotions with regard to letting him do it his way.

One thing that is definitely changed in the last twenty years is that people are living a lot longer than they used to. But with regard to Drako is interesting to note that he was surrounded by people who cared very much for him. But a relationship with Drako was a very one way experience. And when someone does not contact you oftentimes you’ll stop contacting then. I think it was hard for Drako’s friends to cope with this dynamic. And with regards to the obligation of the state or institutions to Drako, I am not sure whether he would’ve been better off in some kind of home or form of managed care. I doubt very much whether he would have been able to live as he clearly wanted to in any kind of institutional context. Obviously with an ageing population much of whom will be suffering from dementia in the future, there is a huge challenge in terms of care to the end elderly and mentally impaired. The Japanese are preparing for this with robots. I’m not sure I have any answers.

8.Drako loved attention and the limelight, what do you think he would have made of the film?

I think he would’ve loved it! I have some footage of him where he filmed himself and once he was aware of the day that dynamic the way he had his face lit up was joyful. That said I thought about it a lot and I wonder if it might be distressing for him seeing something that clearly happened to him without him remembering it.

9. This seemed to be quite a personal journey for you too as a film maker, how did it change you?

Well I think it chipped away at some of my self-involvement. It reinforced my view that if you are going to use someone else in your creative process and artwork you owe them at least as much as you want to take from them. And made me realise that for all my experience in framing shots and everything I picked up about film theory, that my work is not done on the screen it’s done in the audience.

10. And finally, what would you like people to take away from this film?

Whatever they like!

A friend of mine said that what she liked about The Man Whose Mind Exploded was not that it says “Oh Drako’s a bit weird but he’s just like the rest of us.” It says “he’s very unusual but we have to expand our concept of “us” to include him…”

The Man Whose Mind Exploded

Now available on iTunes https://itunes.apple.com/gb/movie/the-man-whose-mind-exploded/id894744010

**** Guardian **** Times **** Independent ****TimeOut

100% FRESH on Rotten Tomatoes

WWW.TOBYAMIES.COM