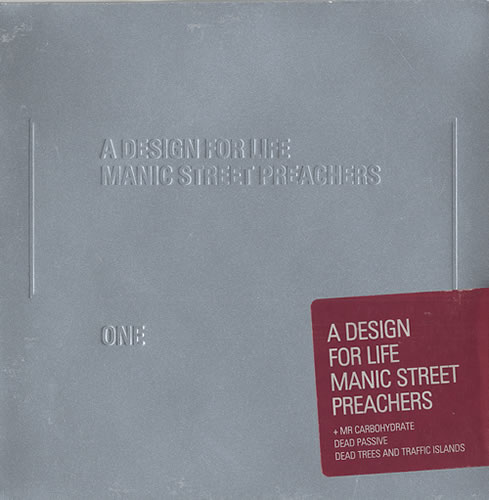

“Libraries gave us power/Then work came and made us free/What price now for a shallow piece of dignity?!” Hollers James Dean Bradfield impassioned with eyes closed, above a backdrop of tumbling arpeggios, cavernous drums and Spector-ish widescreen production that’s steepling strings sway, crescendo and sigh with sadness. This is the unforgettable intro to ‘A Design for Life’ the Manic Street Preacher‘s definitive 90s statement. Tackling the theme of working class identity bassist(lyricist and chief dress wearer) Nicky Wire delivers a staunch defence of the community where he grew up and a belief in the importance of resilience, self-improvement and solidarity as political power attempts to oppress you at every turn– ‘libraries gave us power’ indeed. The memorable video is intercut with quotes and scenes like fox hunting and Royal Ascot to represent what the band saw as class privilege.

This was set against a backdrop of the decimation of their hometown Blackwood, as Thatcher destroyed its mining industry in the 1980s and the economic decline of the early 1990s and many think the miners scars are referenced here with the lines: “I wish I had a bottle/Right here in my dirty face to wear the scars/To show from where I came”.

The bizarre sight of friends arm in arm singing along to its key line ‘We don’t talk about love / We only wanna get drunk’ is an ironic one – are the Manics highlighting the hypocrisy of a working class that only wants to drink and fight, or are they defending its right to do so? I’ll leave that up to you. Regardless, it’s a powerful first statement from the band as a three piece and a epic first single with a elegantly bombastic rock chorus that at the time represented a surprising shift from a band who had musically up until that point dealt only in politically charged glam rock and incendiary proto post punk. It was rather like the shift from Joy Division to New Order…

ADFL bursts to number 2 in the hit parade in 1996, and broke the three Welsh fellas’ album (Everything Must Go) into the mainstream at their time of heaviest loss. Their lyricist and childhood friend Richard James Edwards went missing in 1994 and remains unfound.

In a scene dominated by slogans, crowd like chants and sometimes cartoonish flag waving, Carry on imagery, The Manics were in contrast a band plugged into their surroundings, the working class and their own mythology ‘A Design for Life’ was an epic political statement and stands toe to toe with Pulp‘s superlative ‘Common People’ as the most socially conscious statement of the era. Nicky Wire explained the song’s meaning in an interview with Q magazine April 2011: “It was originally a two-page poem. One side was called A Pure Motive and the other A Design For Life. The song was inspired by what I perceived as the middle classes trying to hijack working-class culture. That was typified by Blur’s Girls and Boys,” the greyhound image on their Parklife cover. It was me saying, ‘This is the truth. GET IT.'”

Drenched in magnificent strings arranged by Martin Greene, and shot with a regret, defiance and a kind of redemption of somehow getting through a tragedy so close to home, the Mike Hedges-produced Everything Must Go recorded in a Normandy Chateaux, was warm and cocooned in its own orbit and quite unlike any other release that year, yet for a very short period the Manics became mainstream, Nicky draped his amp in the Welsh flag at the Brits which was surprising given his views on Wales prior to that, they played a the classic Hillsborough tribute show and rubbed shoulders with Oasis and the like. James Dean Bradfield went onto produce the likes of Northern Uproar and Kylie lending this anthemic string tinged pop sound to them both, the outsiders had become establishment.

The long player Everything Must Go was their most immediate work and struck a chord with a wider public in a way none of their previous albums had. Yet it was tinged with tragedy, regret and a new found functionalism(C&A jeans and t-shirts now replaced feather boas and eye liner)artwork now minimal, as they bravely soldiered on despite still dealing with the grief of the loss of their friend and creative driving force Richard James Edwards.

They would soon fling off the Britpop cloak that they had been smothered in with This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours personal, political and poetic this was the sound of the vast Welsh landscape and loss. It was Nicky’s Holy Bible, melancholic, at times stripped back and at times grand it was a very good post Britpop album that swooped, with grace and pierced with poise…