![]()

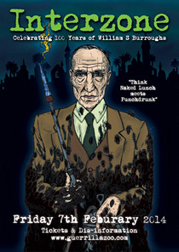

The psychology of jokes can amount for what is so pervasively funny about the works of William Burroughs and the fun of Interzone. The funniness is wound up with a disturbing view of the world. Know as black humor, it’s laughter alongside tragedy or in the face of horrifying circumstances. Interzone attempting to scare you into laughter. The works of Burroughs give a deadpan delivery of the grotesque and Interzone plays on a similar humour from what’s unexplained.

I arrive at North Greenwich station at 8:18 and am immediately shuttled into a cab. The location had been secret up until the day before and I have no idea where I’m going. Nobody in the car says anything until I ask if we are all going to Interzone. (The Guerilla Zoo event celebrating William Burroughs 100th birthday I wrote about here.) ‘I guess that you’re in the wrong car, mate.’ A man upfront says and there’s a few coughs of nervous laughter. I try to smile a bit, and I hope that he means yes.

I know that there is no better way to kill a joke than to try and explain it—to point out, for example, that although John Travolta’s character in Pulp Fiction, doesn’t mean to shoot the guy, but does defeats the humour of the surprise and joke of his death. And that the reason that it’s not meant to be funny, is the same reason why it is. Arriving at a converted warehouse in southeast London is funny because I didn’t know what I was expecting. I move through the entrance—have to crawl through some obstacles, while people dressed as military personal, ghoulish junkies and S&M aficionados shuffle me along. Naked Lunch describes Interzone, as a futuristic wasteland where drug addicts and wasted youth roam. Burroughs, of course, would be in a position where he could appreciate the irony of recreating his nightmarish world for entertainment.

Looking around Interzone, there’s a lot to see. It is dark but a few rooms are lit in a back corner and I walk over to see what’s inside. One has a dreamachine and one looks like a doctor’s office, and a woman dressed as a nurse asks if I have an appointment. I tell her no, but that I’d like one and she scratches my name down on a clipboard. I choose early on to embrace all aspects of Interzone’s immersive experience because the fun arrives from an uneasiness of what’s not explained.

A man with dark shadows colored in pencil around his eyelids makes eye contact with me. He holds my gaze and approaches me. Staring into my eyes, he says nothing as he slips a card into my pocket. He turns and walks away. I watch his back and slide my own hand into my pocket. Removing the card it says nothing on it but: Interzone.

Another problem—even for the most open minded individuals—is, it’s hard to explain what’s funny about, an actor giving me baking powder, calling it bug powder, and saying it’s medicine. Or the fact that a stranger walked up to me and casually put a business card into my pocket. Burroughs’ stories are also sick and surreal. The allusions to phalluses and bodily excretions are countless throughout Burroughs’ work, and are not for the faint of heart.

Not to mention that the particular kind of funniness of Burroughs employs is with a straight face. The fact that all of Interzone’s actors delivered their shctik with such conviction made the experience that much more immersive and enjoyable. There was no getting around the characters that they played. Like the woman issuing classified documents in a dimly lit tent. The card with Interzone slipped into my pocket, allows me to pass into a makeshift tent. She shakes a cane at me and whacks the wooden crate I’m sitting on. ‘Here take this,’ she says and hands me a folder made of black construction paper with: Classified Documents written in silver ink. Inside is a riddle, she instructs me to repeat to a somebody. “The Agent,” She says. “Has a beard and glasses.” Besides describing 85% of the population of the attendee’s, it employs a particular kind of humour.

What Burroughs stories have is a funny kind of sickness, which I personally think is hysterical. Interzone’s humour—not only perfectly timed and executed—is a fun kind of scary. And it is this, I think, that makes Burroughs’ genius inaccessible to people who refuse to look at the dark side of life.

The people who would ‘get’ Interzone are the ones that don’t think that it’s something you get. The central joke: that the horrific facets of life make the good all that much better. Our worst moments are not something to be feared but something to laugh at, much like how the junkies, nurses and doctor are funny. Black humour’s art is in disturbing the comfortable and comforting the disturbed. Like: having been driven in a car, not knowing where you’re going and still not knowing what really happened but glad that it all did.