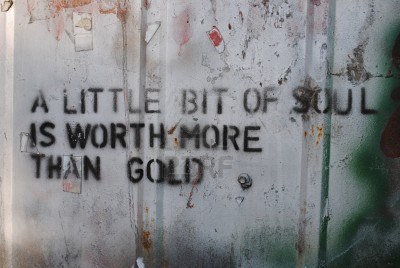

What does soul mean to you? I’m writing primarily in a musical sense, regarding production and integrity to material and performance, but I feel this may extend into a wider social context. It’s no news to proclaim that money and the market are no friends to creativity, and whilst I am no luddite or enemy of technological progress, the perception of what soul actually is is being continually, maybe intrenchably, undermined.

Why are people listening to ‘old’, ‘classic’ artists so much more than searching out new ones? Because, unless they are desperate trendies who care about the judgement of to whom they are talking than their ears, the old music sounds better. Technological limitations can help for sure – you do the best with what you have. When everything is recorded through the same source, and outputted the same way, you’re fairly sure of where you are, and the one-dimensional, visceral nature of the recording process is paramount. Jack White, for one, knows this well.

Fundamentally, everything in the creative process, when it comes to music, has become too thought through, too much a victim of market-planning, brainstorming; of what-will-sell. Recorded music has lost any sense of breath or mystery, where engineers and producers, if not the artists themselves, are obsessed with ‘proximity to the listener’, and promoting that as much as possible. The result is that we end up feeling in fact too close to the artist, and somewhat nauseous in the process. True, very much in opposition to the original punk ideal of removing the barriers between performer and audience – but 90% of recorded punk is unlistenable tripe anyway.

I’m no trained recording engineer, but having recorded three albums myself throughout numerous recording sessions, with varying and subjective degrees of success, and being fundamentally responsible for the production process, I am very familiar with engineers’ resistance to new ideas and anything against the current ‘industry standard’. This industry standard is the very enemy, the reason for our active-maker and passive-listener creative regression, and the essential reason above others that it can be actually hard to listen to the latest Kanye West or Beady Eye albums.

Soulful integrity and durability come from compression of intention and performance, spontaneity, energy, freshness and a degree of hunger, without too much foresight. The Beatles – very much including their producer George Martin – managed this over a series of albums because they were at the vanguard of things, exploiting technology as it presented itself, and because they were inventing the industry, not responding to it – while also placing creative responsibility in the hands of the maker. Of course their sales enabled their record company to accept their every move too, and this was another bonus of the political atmosphere of the time.

Forty years later, a band like Coldplay, capable of writing very beautiful songs, find themselves signing multiple-album contracts, the label responding to sales figures and choices as leverage against the band themselves. Indeed everyone gets rich except for the listeners, who just feel increasingly sad, album by album, as the creative dearth is unendingly exposed. It’s not like anyone actually blames Chris Martin for endlessly trying to replicate ‘A Rush Of Blood To The Head’, except when they remember he himself signed the contract limiting himself to EMI’s concept of ‘representative music’. Play what you said you would, or your dropped. And then sued.

21st century hip hop, with its acceptance of harsh US capitalism as a beautiful, inescapable reality of life, is as big an enemy of real soul as any other. Get rich or die trying. Thanks for the acquiescence of the status quo; we all saw how Obama struggled with the results of that mentality when he first came to office – while the US first and foremost felt the pain – and accept the responsibility of that mentality. With the mass media’s preoccupation with repeatedly stamping this viewpoint on western society, this aesthetic can become embedded, without some kind of a degree of reflection.

Johnny Marr and Morrissey’s rejection of Conservative British Prime Minister David Cameron’s claim that The Smiths were his favourite band is one of the most genuinely punk rock moments I can remember. It’s not that the duo don’t acknowledge that plenty of Tories were and are into their music – their ‘careers’ (another problematic word within creativity) were made by such things – but do not dare inculcate something so real, genuine, impassioned and gracefully acerbic into your cleaned-up, pretentiously baby-carrying and bike-riding public image. Personally I think the presence of soul in The Smiths ouevre is somewhat buried, but their outrage in their music being so misread should be applauded all the same.

The previously-mentioned Jack White appears to be an anomaly, an eccentric quirk in the whole story. Such bloody-minded insistence on spontaneity is appreciated – but on a ‘listened’ scale, he looks pretty lonely. There are others determinedly following a resolute path, but to be quite honest they are all becoming of a certain age (Nick Cave, Tom Waits, Queens Of The Stone Age, Billy Childish, Radiohead, Björk, The Roots, PJ Harvey), and their sales are massively eclipsed by business people-posing-as-

Musicians, writers, apparently almost all creatives-who-mean-it are all stuck within a politically marketed situation between quality of product and various breeds of publishers who already have a market-strategy of what will or will not get through. Between the 60s and the 80s, DJs and quality publications had pretty much the power in dictating taste, as the market for cultural production was in the process of understanding itself. Do you really think Jimi Hendrix, Brian Eno, The Fall, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Television, Butthole Surfers or even Happy Mondays would have been anywhere on the radar without the screaming of critics and reviewers? Individuality, idiosyncrasy, and unique perspectives need support and encouragement in this regulated, marketed world, or soon enough it will be 30 Seconds To Mars for all of us, with no chance of a Lightning Bolt.