The ‘cut-to-the-chase’ summary perusal through Bowie’s twenty-seven studio album legacy continues. Part II begins with the theatrical dystopian canine Diamond Dogs and finishes as Bowie faces the next decade with Scary Monsters and Super Creeps.

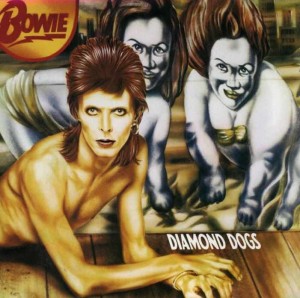

Diamond Dogs (RCA) 1974

“As they pulled you out of the oxygen tent, you asked for the latest party…” And with that the future dystopian, biota canine, leapt from its slumber “onto the streets below”, howling for more.

Bowie never really wanted to be a musician as such. His destiny lay with the grease paint of theatre and allure of cinema. Diamond Dogs of course allowed him to create a spectacle, melding the two disciplines together.

Fate would force the original concept to morph into the achingly morbid and glam-pop genius we’ve now come to love: a planned avant-garde, ‘moonage’, treatment of Orwell’s revered novel 1984 was rebuked by the authors estate. Still, those augural references to state control and totalitarianism are adhered to throughout – both lyrically and in the song titles – but attached to visions of a new poetic hell!

The loose, all-encompassing, metaphysical language may promise melancholy and despair, yet it also knows when to anthemically sound the rock ’n’ roll clarion call too.

Decreed as the leading highlights of the album by the majority –

Diamond Dogs (single), Rebel Rebel (single), 1984

Pay attention to these often overlooked beauties –

Rock’n’Roll With Me (single), Sweet Thing

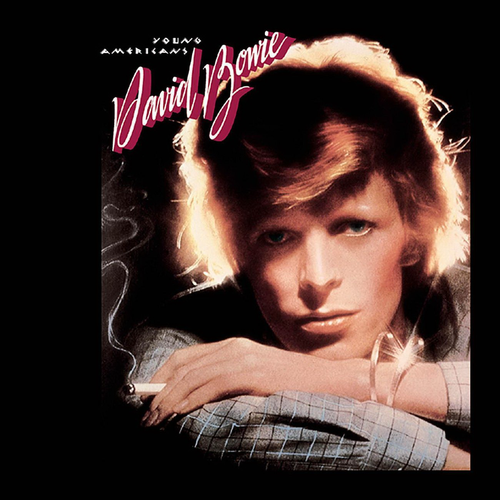

Young Americans (RCA) 1975

Disingenuous to a fault, the cracked actor’s ‘plastic soul’ conversion raised more than a few pencilled-in eyebrows and frowns.

Totally free of his carrot-topped mullet crown, he hotfooted across the Atlantic to Philly, intoxicated by the city of brotherly love’s sweet, lovelorn soul music.

A new face in town, the burgeoning ‘thin white duke’ employed a cast of ethereal backing singers (including an as yet unknown Luther Vandross) and kindred musicians (notably Bowie’s new lead guitarist foil, Carlos Alomar) on his cocaine-fuelled pursuit. Calling in the favours, fellow alienated Brit in residence, John Lennon, helped to write the cynical snide ‘Fame’ (he plays on the recording and adds harmonies too) and let Bowie cover his stirring cosmological trip, ‘Across The Universe’.

Reflective, sophisticated, Bowie and his detractors may have labelled him with derogatory terms, yet there’s no denying it’s another successful musical adoption.

Decreed as the leading highlights of the album by the majority –

Young Americans (single), Win, Fame (single)

Pay attention to these often overlooked beauties –

Somebody Up There Likes Me, Across The Universe

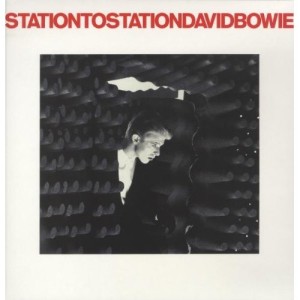

Station To Station (RCA) 1976

A distressed primal howl for the alpine air and culture of Europe were the main motivations for Bowie’s next album. It may have been recorded in LA, but the intention was to reach out across the Atlantic: an escapist gesture of hope to crack the drug habit.

Imbued with, or just unashamedly sucking up, the innovative vapours of the Teutonic music scene, those previous soul allusions were now entwined with the pan-European express of Cluster/Harmonia (and all the various Roedelius and Dieter Moebius projects), Kraftwerk and Neu!

The autobahn was already spoken for, so it would be the allure of continental train journeys that oiled the wheels of the album’s minor opus title track. Heralding the “return of the thin white duke”, Station To Station traversed disco funk (‘Stay’), doo-wop futurism (‘TVC15’) and featured Bowie the Shakespearian glib, warbled crooner (‘Word On A Wing’, ‘Wild Is The Wind’). Oh yes the note register was high all right; a resounding plaintive cry before that all-immersive dip into the Berlin years.

Decreed as the leading highlights of the album by the majority –

Station To Station, TVC 15 (single), Golden Years (single)

Pay attention to these often overlooked beauties –

Stay, Wild is the Wind

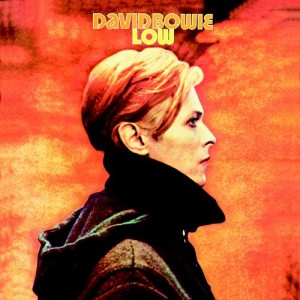

Low (RCA) 1977

Damn Nicholas Roeg and his predilection for the new age transcendental folk of John Phillips, The Man Who Fell To Earth soundtrack was Bowie’s.

Those burgeoning precursor examples of what would eventually become Low, proved too ‘off-world’ for the film director. Bowie kept the image though (the second LP to use a still from Roeg’s movie): his forlorn, marooned gazing profile set against a burnished alien sky, a perfect indicator of what waits inside the sleeve.

Heralding the triumvirate of empirical ‘Berlin’ albums (though much of the material was recorded in France), Low featured the ‘dream team’ of Brian Eno and Tony Visconti. A bookend to that year’s concomitant Heroes, its Northern European, Lutheran melancholy reflected where Bowie’s mind was wondering. Druggy delusions of LA were replaced with the darker underbelly of Berlin’s smack culture (see Christiane F), as Bowie and his Teutonic sightseer buddy, Iggy Pop, immersed themselves in the shadow of a cold war miasma-walled city.

Much to the surprise of the country’s musical vanguard, his adoption of the German new wave received all the acclaim they’d been denied. Yet there’s no denying that he gave the Krautrock blueprint a sheen and wider appeal, which only Kraftwerk and managed to achieve.

Half spiritual progressive soundtrack, half assuaged meditations on addiction, Low may still lyrically feature the themes that dominated his torrid lifestyle (drugs, isolation, marriage problems), yet the sound had once again moved on – those soul postulations now just a distant memory.

Decreed as the leading highlights of the album by the majority –

Sound And Vision (single), Always Crashing In The Same Car, Be My Wife (single), Warszawa

Pay attention to these often overlooked beauties –

Breaking Glass, Subterraneans

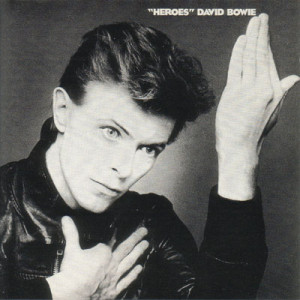

Heroes (RCA) 1977

Part two of the synonymous Berlin tirade could at least claim to have been recorded there. The Hansa Ton studio stood literally within spitting distance of the Russian border guards: a constant reminder of the foreboding presence of the Communist eastern bloc, breathing down their whey necks.

If Neu! weren’t already gnarled by Bowie and Eno’s marauder raids on their transcendental futurism, then borrowing the ‘Heroes’ album/single title from their Neu! ’75 LP, all but sent the duo’s Michael Rothar into a piqued fit. Rumours abound that Rothar was actually originally approached to play guitar on the subsequent album. He declined, allowing Carlos Alomar and (just flown in for one day only from NY) Robert Fripp to lay down the exploratory industrial winds and bends for posterity.

Apart from the arching, attenuate linear guitar anthem to star-crossed lovers – caught in the shadows of the Berlin wall – Heroes, the observational moody paean to the city’s heavily Turkish-populated district Neuköln, and the ironic tribute to Kraftwerk’s Florian Schneider, most of the material doesn’t allude to Bowie’s German residence.

Instead the themes concern Bowie’s LA drug years (‘Beauty And The Beast’), eastern contemplation (‘Moss Garden’), fantastical horizons (‘The Secret Life Of Arabia’) and the conceptual performance of Chris Burden (‘Joe The Lion’).

Decreed as the leading highlights of the album by the majority –

Beauty And The Beast (single), Heroes (single), V-2 Schneider

Pay attention to these often overlooked beauties –

Sons Of The Silent Age, The Secret Life Of Arabia, Blackout

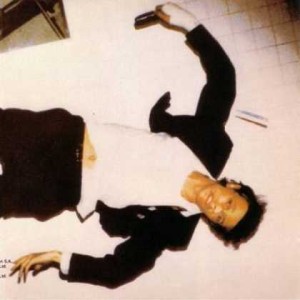

Lodger (RCA) 1979

The most ‘at odds’ album in the Berlin trilogy, Lodger was greeted with indifference and bewilderment on its release. Recorded entirely in Bowie’s other adoptive city, New York, between dates on his 78 tour, its shorter, snappier and angulated songs aped the awkwardness of Eno’s own solo material more than ever. This partnership though would fizzle out during the process, yet their third album together is easily as inventive as the previous two chapters.

Sophisticatedly disjointed, the oblique ‘strategy cards’ guided lyrics seemed calculating and sardonic (especially on the glib, sneering ‘DJ’). Bowie performed as though still in character, postulating from an aloof safeguarded position.

His clipped, alien, Cary Grant burr deliberated on masculinity (the unruly guitar avant-pop beast, ‘Boys Keep Swinging’), the anguish of mental illness (‘Fantastic Voyage’) and the Kenyan ‘veld’ (‘African Night Flight’).

Those Germanic influences still permeated, even though Bowie’s mind had drifted back across the Atlantic: Klaus Dinger and Michael Rothar found ‘Red Sails’ an uncanny veiled tribute, and ‘Yassassin’ floats very close to Can’s own Turkish-flavoured reggae grooves.

A tough sell and hard thought listen, but still worthy of its place within the revered Berlin series.

Decreed as the leading highlight’s of the album by the majority –

Fantastic Voyage, DJ (single), Boys Keep Swinging (single)

Pay attention to these often overlooked beauties –

African Night Flight, Look Back In Anger

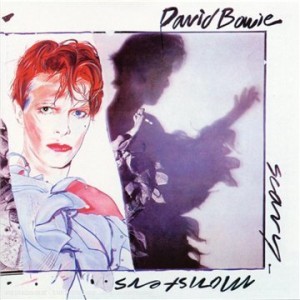

Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) (RCA) 1980

Upon the threshold of a new decade – an overtly garish and greedy one at that – steely Bowie produced a career high with his 14th studio album in just over a decade. Kept awake at night and harassed by visions of an industrial, anvil beating, future present, the gnawing, grinding and extruded backing track sounds like it was created in a furnace.

Minus the theatrics of Diamond Dogs, Scary Monsters features a mature Bowie, adorned with a sloppy mix of cyber-harlequin and Pierrot clowns make-up and costume; preoccupied by his own past meditations.

I feel like I’m repeating myself, but the omnipresent spectre of drugs pops up again as Bowie revisits Major Tom the ‘junkie’ – the poor soul’s been rattling around in that capsule all alone for the last ten years. But thankfully he has other more pressing matters to focus on, including the fall-out of his divorce from Angie; the nature of celebrity; and mental illness (another constant worry and stress that hounds and informs Bowie’s work).

Bowie the elder statesman (still only 36 years of age) also takes a thinly veiled swipe at the new guard, with fretted crooning diatribes on the supposed ‘computer world’ myth of Gary Numan and the consequences of finding fame at a young age (‘Teenage Wildlife’), and a sardonic automated dismissal of the fashionista sect, ‘Fashion’.

With a perfectly pitched, emotively shivering version of Tom Verlaine’s (former Television guitarist and solo artist) ‘breaking rocks redemption’ song ‘Kingdom Come’ to boot, Scary Monsters would be the last truly classic Bowie album for some time. Ending a solid run of experimental exploration, not seen again until another decade, as Bowie chose to peruse a more congenial and commercial path in the 80s.

Decreed as the leading highlights of the album by the majority –

Up The Hill Backwards (single), Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), Ashes To Ashes (single), Fashion (single)

Pay attention to these often overlooked beauties –

Teenage Wildlife, Kingdom Come