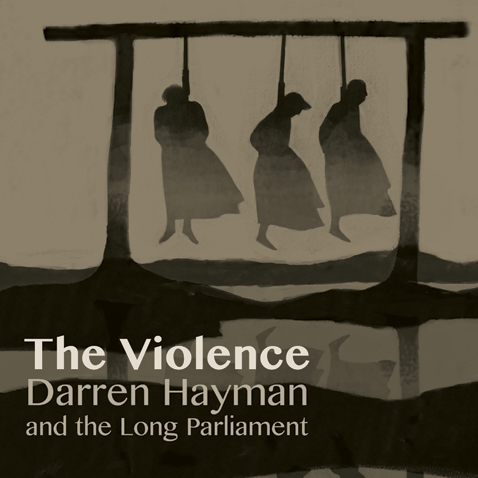

Chronicling the mundane predilections and modern state of his native Essex on previous albums, the adroit Darren Hayman now lends his assuaged methodology to the infamous witch trials that took place in that very same county, over 350-years ago.

As part of his disparaging/homage to Essex, Hayman has finally completed the trilogy of LPs that began with Pram Town and Essex Arms, with this conceptual elegiac tome The Violence. Although planned and worked on for a considerable time, this twenty-song suite has caught the recent witches zeitgeist that’s prevalent in music, TV and the theatre: Maxine Peake’s Lancastrian burred narrated guest spot on the Eccentronic Research Council’s brooding, industrial synthesizer paean 1612 Underture, and the bewitching dual cover opus of both Alex Harvey’s ‘Isobel Goudie’ and Maddy Prior’s ‘The Fabled Hare’ by Sproatly Smith, are just two recent examples of that witch trials fascination.

Through the Middle Ages, Elizabethan and well into the 17th century, the zealot purges of Europe even spread to the Americas: In particular with, perhaps, the most synonymous trials in both literature and history, Salem. Paranoia, jealously and plain old ignorance drove on these tragic “cleansing” during tumultuous periods of uncertainty, and in The Violence’s case, civil war. Replace the supernatural and esoteric with politics, or beliefs, and you’ve travelled forward hundreds of years into the modern world. Obviously the rather unsubtle pretext to all this century’s and the lasts fabled yarns and profound witch trial themed works, are also condemnations on the present. The best example of this is Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, a challenging exposé of the cold war McCarthyist Communist trails – of which he himself suffered.

Always a constant, the inquisitional miasma of intolerance and “extreme prejudice” remains a very humanistic trait when things turn sour, or society finds itself in crisis. Hayman’s magical indie folk oeuvre endeavours to convey this, whilst bringing to life the divided harsh landscape of an England, devastated by war; a peruses project you could say which is duly summed up by the songsmith himself in his artist statement: “It’s easy to become trapped by own tropes. I write easily about modernity and pepper my lyrics with slang, brand names and colloquialisms. I wanted to write about something in Essex’s past that spoke of its strangeness and also forced me to write in a language suitable for another period.”

Encapsulating those years perfectly with the albums title, a context of fear is evoked through a range of disarming and beguiling odes, sonnets and instrumental interludes. So movingly charming and suitably sad, Hayman’s style is to coat the unpleasant with varying degrees of loveliness and harmony. To indolently jolt the listener with a litany of punishing realism whilst those gentle melodies effortlessly meander on their merry way.

The facts: During the burgeoning years (1644 – 1646) of the English Civil War (1642 – 1651), approximately 300 women from the eastern counties of Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk were executed for various tenuous crimes, slights and for…well, for nothing more than association – most of this was either tortured or threatened out of the poor souls. Take the cruel misfortunes of one of The Violence’s real-life principle players, ‘Elizabeth Clarke’, the catalyst for the whole Essex “witch cull”, Clarke was persecuted by the infamous Witchfinder General Matthew Hopkins (played with ruthless relish by a mooning Vincent Price in the low-budget 1968 film of the same name) in 1645. The 80-year old, one-legged spinster’s plight was made worse by the fact that a fellow accused “witch” Rebecca West, gave evidence against her to evade the hangman’s noose.

Incidentally Rebecca’s own mother, Anne – given a plaintive send-off by Hayman on this album – was another victim of Hopkins trials, yet she managed to escape execution by confessing to “sleeping with the devil.”

Before the bloodlust and zealously ended, up to 200 innocent unfortunates found themselves implicated and condemned by the Puritan inquisition, though Hayman has singled out the saddest of hymn-like eulogies to Elizabeth with a first-person narration from the scaffold. Awaiting her fate, our aged heroine poses the all too real worries of, “Whose going to dig my grave?”, and, “Whose going to pull on my legs when I swing?”.

Of course, at stake was the very future governance and control of the country, as the parliamentarian forces clashed with the Kings. Hundreds of years of Royalist allegiance and dependency couldn’t be changed in a matter of weeks, months or years. Cromwall may very well have ascended to the dubious leadership of the Roundheads, yet even in this opposition camp there were multiple ideological and religious differences which at various times spilt and threw the cause into chaos. In fact the Civil War was a much closer run contest than were led to believe.

As history dictates the former obscure gent became every bit as tyrannical as Charles I – though we shouldn’t automatically let his achievements go unnoticed. So you have Hayman’s “We are not evil” (from the eponymous song) repetitive chant from those who carried out the misguided role as “cleansers”. Motivated by the fear and isolation that may mark them out as a sympathizer, or dark arts practitioner, the eager enthusiasm to join in with the persecution least they themselves end up at the wrong end of the hangman’s rope, must have seemed almost obligatory.

Equally the Puritan’s – not just a question of democracy vs. autocracy but a religious battle to the death – finger of guilt pointed at the Royalist’s own poster boy, Prince Rupert of The Rhine, with propagandist allegations that his famous companion dog, Boye, was endowed with magical powers. Accompanying the Prince cavalier into battle, the so-called “shape-shifting familiar”, luck finally ran out at the battle of Marston Moor in 1644. Given a short instrumental soundtrack, Boye’s tune is a minimal thoughtful pause that’s more reverential than the comedic charges alluded to a pet deserves to be.

Rather touching, though tragically poignant as we know the dire outcome, is the attentive cooing love song to Charles I’s Catholic bride, ‘Henrietta Maria’: “You’re three times prettier than your portrait”. Hayman’s admonitory, surreptitious motives unfurl themselves at a languorous pace, the consequences of the consorts beliefs played out to a touching requiem.

Charles I’s own bloody end at the hands of the executioner is documented on both ‘Kill The King’, and with the litany political instrumental balled ‘A Coffin For King Charles, A Crown For Cromwell And A Pit For The People’: a querulous satirical prose that reflected the dreaded realization of “meet the new boss, same as the old boss” dictate.

The main focal point is the witch trail victim’s plight. The most beatific and sweetly crooned of these led songs is the waltzing ‘Vinegar Tom’. The central character from the Feminist playwright Caryl Churchill’s 1976 play of the same name, Vinegar is a witch’s cat (also known as a familiar, much like Prince Rupert’s dog, Boye), or as in real-life events an ordinary moggy that was condemned along with its owner. In this stirring British Sea Power-esque (circa Open Season) incarnation, a protagonist and her pet stare futility and fate in the eye, dreaming of escape from the inevitable.

However, it’s not all mournful, as the more upbeat shuffling ‘Impossible Times’ anthem shows. The feature tune and lead-in for the whole experience you’re about to absorb, this pastoral number lays out the “lie of the land” so to speak, even though it contains a series of vivid descriptions on the ill-starved countryside, poverty and state of the nation.

Ambitious in scope – clocking in at around eighty-minutes – The Violence could do with some cutting here and there (an instrumental too far perhaps?). The flow and cadence tends to lag and lack luster, dragging its heels in the gloomy mire as it wallows. But these are really minor qualms and quibbles when presented with such an exhaustive and arduous songbook, which on the whole brings important atavistic events – in this case the often misguided, forgotten and dismissed English Civil War – to life.

Even the album’s release falls on the famous date of the Gunpowder Plot, another allusion to the importance of history, and a timely reminder of the birth of this country’s democratic process and all the connotations that go with it.

It’s bleeding obvious that Hayman gives just as much importance to the individual as he does the grand scheme. And for that we should applaud him.

Released 5th November 2012

[Rating:4]