For a band whose methodology of recording was built on endless weeks, days and hours of, mostly, unregulated jamming and experimentation in their own purpose-built studio, it seems, on the surface, surprising that there aren’t more of these exciting lost tapes hanging around. This particular bundle of venerated studio work, shelved soundtracks, live performances and unused album sessions, was only rescued by chance when the German Rock’n’Pop museum (which sounds a whole lot hipper and on-message then that petty sad-ass Rock And Roll Hall of Fame) brought and moved Can’s legendary, Wellerswist (Cologne), studio, piece-by-piece to Gronau in 2007; those treasured recordings discovered stowed away in a locker, filed in a vague manner.

It soon became apparent that these archived but forgotten about, barely legibly labelled reels would prove to be illuminating, insightful and on a par with anything the kosmiche explorers ever released: Oh, and it energetically kicks like you wouldn’t believe!

Of the 30-hours unearthed, the group’s magnanimous sonic genius, Irmin Schmidt, with the aid of his musical collaborator of recent years, , and son-in-law, Jono Podmore (Kumo and Metamono), have whittled and edited it down to an eclectic 3-hours, stretched over a triumvirate of CDs (a vinyl version is promised at some point in the future).

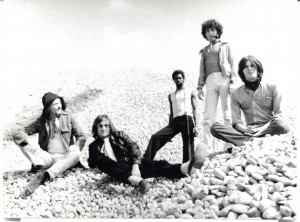

Recorded between 1968 and 1977 in both the former cinema-turned ‘Inner Space’, Wellerswist, and original iconic, castle-pile, Schloss Norvenich, this imbued gamut displays every nuance, facet and truly adventurous stroke that Can were both renowned and worshiped for, with a few surprises thrown-in for the ‘head music’ connoisseurs.

Schmidt and Podmore couldn’t have picked a more befitting start to proceedings than the opening ‘motorik’ powering soundtrack, Millionenspeil. Commissioned for the 1970 German TV film, Das Millionenspeil – a sort of less camp and gratuitous precursor of The Running Man that features a survival/on-the-run game show plot – it throbs and buzzes with a fuzzy-static charge of probing Holger Czukay bass, Michael Karoli vibrato resonant guitar and Schmidt brewed oscillations, whilst the ‘man-machine’ drumming of Jaki Liebezeit maintains an unblinking command. From that early Velvet Underground influenced, brooding, sleazy menace, to the step-change shift into a wild esoteric version of Dr.No style calypso, Can score enough musical changes to fit three unrelated movies together.

The motoring tempo is kept up by the following Malcolm Mooney-led, impromptu mantra, acid-rock freak-out, Waiting For The Streetcar. Somehow finding himself embraced into the early Can line-up, the African-American, lost in a strange land, sculptor, channeled Arthur Lee, Jimi Hendrix and The Last Poets into an, often, psychotic kind of beat poetry, crossed with improvised anecdotal ravings. His brief apprenticeship only lasted until December of 1969, before the ‘paranoia’ and schizoid episodes finally got the better of Mooney; a certain individual persuading him it would be better to return back to the states, forthwith. Yet, Mooney is served very well on The Lost Tapes. Waiting For The Streetcar has him repeat, ad nauseum, the title, with just a few alterations; pulled from the live castle of Schloss Norvenich event that this track is cut from – Can would often perform shows for the owner in the art-gallery above their inner sanctum; Mooney ad-libbing lyrics and riffing off the arty audience.

On the creepy, When Darkness Comes, Mooney acts like a Voodoo magi, fired-up and deeply unhinged. However the bombastic, pulsing and cool-as-fuck, Deadly Doris sees Mooney stutter excitedly, babbling the repetitive looning, “A-dead-dead-dead-dead-dead-dead-deadly Doris!”; throwing in the odd Beatles, “Sexy Sadie”, reference for a laugh.

CD number one also includes some striking majestic escapism: the interlocking segment halcyon, Evening All Day, and acid-folk, Obscura Primavera, prove particularly evocative and moving. The true standout must be the 17-minute, concatenated suite, Graublau; an album’s worth of ideas that merges The Mothers Of Invention, Stockhausen, The Seeds and the Soft Machine into one giant melting pot, bound for a trip into the future.

CD two sees an equal division of labour, Mooney sharing vocal duties with the wistful cooing, Japanese vagabond, Damo Suzuki. Mooney’s contributions include the Monster Movie era, lolling, Afro-psych backed, ode to ‘the ladies of the night’, Your Friendly Neighbourhood Whore; a part strolling drug anecdote, part soliloquy travelogue entitled True Story; and the spindly, subdued (later to become Soul Desert from the Soundtracks album) Desert: Mooney’s vocals literally dry-up; sounding more and more dehydrated as he metaphorically crawls across the barren landscape.

Meanwhile the shy, almost effete, Suzuki can be heard testing the waters on a series of Tago Mago, Ege Bamyasi and Future Days period sessions that never made the final official albums, or subsequent bootlegs. The best of these, Dead Pigeon Suite (of which I assume was originally set to be included on the film soundtrack for Dead Pigeon On Beethoven Street), expands on the finalised Vitamin C, taking the end section ripples on a charming, pastoral Tibetan journey, before morphing back into the originals energetic breakbeats, and throwing in the odd fragment of Pinch to create a unique remix style mash-up.

If anyone needed reminding that Can were first and foremost an improvised live sensation then both this and the third section of the Lost Tapes tome digs out some inspiring shock-and-awe, cosmic performances. None more so than the ‘avant-hard’, sprawling rhythmic feast, Spoon, which takes the inaugural 3-minute version on a 16-minute travail to the Twilight Zone and back (complete with an appreciative audience at the start, whose baying hand-claps stoke the Can engine). On the last of the CDs, both Mushroom and One More Night (entitled One More Saturday Night here) receive a thorough going-over. Varied time-signatures, languorous builds and sauntering grooves twist the formula into new shapes, yet retain the key riffs and motifs, though Suzuki has his work cut-out trying to fit the lyrics into the more free-roaming improvised sonic landscapes.

Perhaps it could be argued that the most wild and unfamiliar explorations are found on the third and final CD of this boxset. Can’s signature – and often most cited – theme tune of a sort, Mother Sky is in evidence on the galloping drum-roll propelled, On The Way To Mother Sky. Those recognizable wrestling, bended guitar riffs and hypnotizing monolithic bass lines are all in there somewhere waiting to break-out, obscured in part by a jarring Vincent Price horror-show of flaying organ.

During the mid-seventies Can became seduced and influenced greatly by music from the African continent, alongside an adoption of reggae, funk, and perhaps their most berated choice of music, Euro-disco. Without a talisman vocalist to prop up at the front (Mooney left long ago on doctors orders and Suzuki got hitched to a Jehovah’s Witness; turning his back on the group in the summer of 1972) Can now relied on their, shy, wistful, guitarist, Karoli, to utter and woe pliable passages, from Future Days onwards, though none of these are featured, or turn up on this compilation. In a way Can’s most credible work began to fizzle-out and lose its way by the time we get to their 1974, glam-rock, Floyd-esque, Landed album. One of the more nebulous trips from that -often over-looked – LP, Vernal Equinox, is shown in an even more heavenly-elevated light on the mysterious, Midnight Men; morphed and extruded to include some startling rich and ethereal thrills.

More difficult to fathom is the reggae-boogie, San Francisco police car-chase sequence riffing, Barnacles, which sounds like the missing link between the Flow Motion and Saw Delight eras, and has former Traffic bassist, Rosko Gee (who along with Traffic’s Ghanaian percussionist, Rebop Kwaku Baah, joined Can in 1977; featuring on the last three albums and performing with them live until the bands break-up in 1979) performing some angulated, funky, and down-near salacious bass routines.

Odd flotsam like the grumbling French monologue, E.F.S 108 – another, either, inspired or throwaway musing from the Ethnological Forgery Series that features so heavily on the Limited/Unlimited Edition compilations of discarded and shelved ideas – and the instrumental, quivering love paean, Alice, were understandably…well, canned, but progressive toe-curlers like the organ tantrum, Zeppelin’s colliding up above, buzzing, Godzilla Fragment, and choppy Shaft guitar licked, jazz work-out, Network Of Foam, deserved a whole lot better!

Reinforcing the Can legacy and myth, The Lost Tapes is a genuine rare artifact that sounds as fresh now as it did over forty years ago – either Can were not just ahead but light-years into the future of nearly everyone else, or a sad indictment on the last four decades of music that shows we haven’t been able to surpass or build-upon their original template. This superbly collated 30-track overview of unreleased musical nectar may have taken a long time to emerge from the bunker, but it’s been worth it, the imbued revelations pulled from the mists of time, proving to be more than anyone could have hoped for.

18/06/2012

[Rating:5]

http://mute.com/mute/the-lost-tapes-out-18-june-2012