Brother Records/ Stateside 1971

Recorded Jan – June 1971

POST-TRAUMATIC SURF

The Beach Boys, a name that started off life as a gimmick attached to the teen surf craze of the early 60s, now hung in the air, stale and malodorous like a serving of oysters, way past their sell by date. After the, rightly, revered accolades of ‘Pet Sounds’, and the failed travails of ‘Smile’ (the most eagerly anticipated and pertinacious of pop holy grails; released as a hastily scrambled together, and disappointing ‘Smiley Smile’ in 1967) the Hawthorne, California boys had fallen from grace; stuck producing music that failed to stand muster as the 70s approached. In an ad hoc, listless at times, fashion, the group had lurched from soul music – 1967s surprisingly imbued ‘Wild Honey’ – to inspired moments of proto-Brian Wilson assiduous songwriting, on the 1970 ‘Sunflower’ LP – a record held in high regard by enthusiasts.

The sextets youthful, time immemorial appellation was out of step with the advent of West Coast psychedelia, acid rock and the growing politicised movements, happening in culture: under the genius but unfathomable malediction immure mind of Brian Wilson, they had lost their pioneering spirit, and fallen spectacularly behind; imploding on a grand scale. By 1970, the mentally challenged and wired semi-locked in syndrome addled Brian now only flashed sporadic glimmers of that ‘genius’, with each subsequent album release only ever removing hope that it would ever return. Luckily there were five other members to rely on: well to a point!

The group were split into two constantly squabbling and warring fractions: on one side stood the Wilson brothers trio of Brian, Carl and Dennis; the flawed talent so to speak, yet also the most wearisome of heavy drinkers and dopers, whilst on the opposing wholesome side, stood the Wilson’s cousin Mike Love, and the straights, Al Jardine and Bruce Johnston. The Wilson clan tended to have all the drama, with chief instigator Dennis at the deuce coupe wheel: Dennis the sun-kissed and anointed God’s gift to women, and general hell riser had a talent for attracting danger, which proved almost fatal. Step forward the beguiling relationship between him and the self-appointed prophetic sex-crazed guru and devils ambassador, Charlie Manson; the man who alongside Altamont brought an abrupt end to the 60s dream – Dennis was initially turned-on by all the free-loving laid on by the wily Manson’s ragtag of jail bait and gonorrhea infected followers, before hailing the nut-job as a musical seer, and recording his songs. For once, Dennis had been secretly improving both his own songwriting skills and piano-playing, whilst pursuing a career away from the Beach Boys – an ill-fated role in the road-racing cult movie ‘Two-Lane Blacktop’, alongside James Taylor, failed to ignite. His first solo single would be released on the cusp of the 70s, and some of his material would make it onto ‘Sunflower’. Emotive and critically sound, it seemed his songs would become an integral part of ‘Surf’s Up’, yet the triumvirate of ‘4th Of July’, ‘Fallin’ In Love’ and ‘Wouldn’t It Be Nice To Live Again’, all failed to make the final track list cut – though Dennis would have the last laugh when his diaphanous classic solo LP, ‘Pacific Ocean Blue’ came out years later. Middle sibling, Carl, would steer the band through the turbulent four years that led – in my eyes – to their second finest album. Stepping into Brian’s shoes, handling production responsibilities – to a large extent – and tentatively arranging compositions: he was in a sense the groups steward. Both a crucial songwriter and vocal talent, Carl helped carry on the good fight.

In the rival camp, the arriviste new-age pious convert of transcendental meditation, Mike Love, always rubbed the Wilson’s up the wrong way, and clashed over every detail – he once declared the pop masterpiece, ‘Good Vibrations’, was nothing more then “avant-garde shit”. Sticking to the sunshine pop formula, and basking in the adulation of radio-friendly branded Beach Boys fare, Love would not just throw a spanner, as a whole tool factory’s into the progressive and dreamy ambitions of Brian’s increasingly experimental works. Standing alongside him, both Al Jardine and Bruce Johnston would keep out of the numerous confrontations and scrapes; knuckling down to act as steady anchors under the unstable, leaking musical Mary Celeste.

END OF THE TRAIL

The task of restoring The Beach Boys back to glory, haphazardly fell into the lap of radio DJ, chancer and Walter Mitty character, Jack Rieley. A chance meeting between both Rieley and the increasingly paranoid Brian, took place, rather surrealy, at the Wilson patriarch’s pet project, Radiant Radish health food shop – Brian’s good-living obsession led to him purchasing the store; though he lost interest rather quickly. Always on the make, Rieley ingratiated himself into Brian’s confidence and persuaded the group to plug their current album – ‘Sunflower’ – on his show. His amiable manner, intellect and ideas were lapped-up; especially when he backed-up his credibility with a dodgy CV – a prestigious journalist award and claims of friends in high places, were in fact fabricated. Weeks after appearing on Rieley’s KPFK radio show, he wrote a St.Paul’s epistles to the Corinthians sized edit to the boys, outlining how he could put them back at the top of the music business. Impressed, they promptly hired him to start work on pulling them back from the wilderness.

Rieley’s task begun when he bestowed Carl Wilson with the title of ‘musical director’, in recognition of his role, holding everything together since Brian’s psychosis took over. He then tore into the group for their failure to engage with the socially political landscape: they were adrift from contemporary America. Ecology, Vietnam, the pathos of change, plight of the jobless, and the forlorn symphonies on the loss of innocence would now be the order of the day: wrapped up in a tender blanket of ‘post-Woodstock’ lament to injustice – they weren’t exactly shouting from the soapbox, but rather soothingly delivering their message in a whisper. Rieley also insisted that Brian should finish the abandoned magnum opus, ‘Surf’s Up‘ song: the set-piece leitmotif, originally destined to grace ‘Smile’. The legendary sophisticated, ethereal suite, was first conceived way back in 1966, and involved Brian’s hip L.A literature savvy collaborator, Van Dyke Parks, whose sagacity, recondite adroit lyrics proved too multi-layered and esoteric for the rest of the group to comprehend. Shelved unceremoniously, this rhapsodic diegesis spun eulogy was an inspired work of utter genius – a word you can never use too often around Brian – that flowed with such proscenium almost F.Scott Fitzgerald-esque descriptive lines as “A diamond necklace played the pawn/hand in hand some drummed along to a handsome man and baton”, and, “The glass was raised/ the fired rose/the fullness of the wine/the dim last toasting/While at port adieu or die”. This is the kind of song that produces reams of study: “Columnated ruins domino” anyone? – something to do with fall of Rome I’m led to believe.

In typical characteristic style, Brian refused to entertain the prospect of finishing the song, which Rieley insisted would be the center-piece and title of the album. It was Carl who had to save the track from languishing in the vaults. He pieced together, from demos and scattered companion segments a three-act grand elegiac. Overdubs were added and a new final rousing chorus (“Child is the father of the man”), sung by Al Jardine, was tagged on the end and speeded up to fit the 1966 original tentative foundations. Brian’s interest was thankfully pricked, as he raised from a stupor and helped master the final edit with the, much put upon, resident engineer, Stephen Desper: the poor soul who was forced to record Charlie Manson’s demo – a session which ended in a lively debate between the two (that good old prankster pulled out a hunting knife on Desper at one stage). Poignant, frail and mournful, Brian’s original performance of the song perfectly reflects the general mood of America’s 60s hangover, on this sad choral paean that rally’s around the hopes of the children.

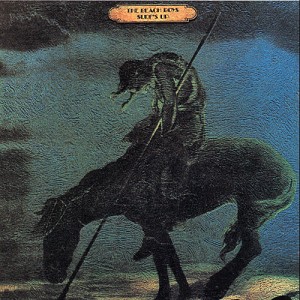

Further more the choice of artwork which furnishes the LP, is an extension of both the Beach Boys allusions to the Native Americans plight and fight for survival, and as a cause for the group to spiritually engage with. Their own Brother label uses Cyrus Edward Dallin’s 1909 bronze statue, ‘The Appeal To The Great Spirit’, as a logo, and ‘Surf’s Up’ borrows the plaintive iconic ‘End Of The Trail’ statue by James Earle Fraser to illustrate further the common theme of dignity. Silhouetted against a morose coloured background, our tragic warrior with head bowed in defeat, seems to perfectly sum up the dark side of that “frontier spirit”.

“A BROKEN MAN TOO TOUGH TO CRY”

Despite withering in a languorous state, Brian Wilson could still produce both endearing, pertinacious melodic exhalations. Perhaps his second best contribution, ‘Till I Die’, is a wistful, diaphanous hymn, dedicated to some quasi-mystical search that seeks to unburden the mind. The lyrics could be considered as being dressed-up platitudes of Eastern metaphorical thought, crossed with Californian new-age therapy: “I’m a cork on the ocean/floating over the raging sea/How deep is the ocean? I lost my way”. If this were some second or third-rate act, then such hippie shtick could be cringing, yet somehow with its stirring haunted organ melody, reflective pursuit for peace heard in the traversing harmony, or the heart-achingly moving vocals of Carl; we feel their pain convincingly – not unsurprisingly, Mike Love dismissed this song that had taken Brian over a year to finish, though he later changed his mind and even sang it on tour. However the next two efforts left a lot to be desired. Co-written with the sprightly Al Jardine, ‘Take A Load Of Your Feet’ attracted certain disparaging comments from critics, and a disgruntled Dennis – justifiably so considering this piece of light-relief bumped one of his own superior tracks off the album; something he put down to envy. Almost like a whimsical buffoonery break from the elegiac, the ecological pastiche sounds more at home on an episode of Seasame Street. Essentially a folksy-psych instruction memo on taking care of your health, its sound-effects accompanied lyrics are pure comedy.

Comedy, or a genuine sad allegory about the state of Brian’s unbalanced mind, ‘A Day In The Life Of A Tree‘, on the surface, is another eulogy and warning message to stop our destruction of nature. With its fairground organ, sonorous Moog bass and reverential church service tune, this dejected psalm pleads evocatively of our greenery’s struggle to breathe. If rumours are true, then at the time no-one would sing the nigh depressingly emotive vocals: the band mates had a point, when Brian wrote such melancholic lyrics as “Feel the wind burn through my skin/The pain/the air is killing me”, and the tearful climatic refrain “Trees like me weren’t meant to live/if all this world can give/is pollution and slow death”. Rieley carried the can and sung the lead, helped by Van Dyke Parks. Competent but slightly hovering off-key – in a good way – this track is either cherished or discounted.

Keeping with the topical motif, the well-positioned, in name only, Beach Boys tackled the polluted seas – apart from Dennis, the rest of the group didn’t actually surf – ‘Don’t Go Near The Water’, penned by Love and Jardine, is an aquatic bouncing, bass plonking, doo-wop sermon; a disaster-themed warning to the ecological domino-effect that starts in the waters: “Oceans/ rivers/ lakes and streams/have all been touched by man/The poison floating out to sea/now threatens life on land”. Originally included in the sessions for ‘Sunflower’, this profound goofball protest seemed to perfectly fit in with the Beach Boys new “right-on” image. Love continues to roll with the eco-political stance on his solo-penned, cynically observed, ‘Student Demonstration Time‘ diatribe. Channeling, or rather wholeheartedly reworking, the 50s R&B classic, ‘Riot In Cell Block Number 9’ via The Beatles ‘Revolution’ – jut check out that fuzzed-up guitar riff – Love replaces the lyrics with an up to date, post-dream is over, take on the Kent State anti-Vietnam war demo, and general civil unrest. In a vaguely Country Joe, and Grateful Dead way – The Beach Boys shared a stage with the Deads in the April of the same year, as part of their drive to appeal to the hip generation – Love uses a megaphone to sceptically blast out pessimistic truths: ‘The violence spread down south where Jackson state brothers/learnt not to say nasty things about southern policeman’s mothers/Nothing much was said about it and really next to nothing done/The pen is mightier than the sword/but no match for the gun”, the crux being that these motherfuckers wouldn’t flinch from quelling protest, or as the Maharishi pupil Love would sing, “I know we’re all fed up with useless wars and racial strife/but next time there’s a riot/well you best stay out of sight”. This time around it would be Brian who turned his nose up at a song: voicing concern over its lyrical content and intensity, though it may have been met with approval from draft-dodger Carl, who three years previously had declared himself a conscientious objector, and only spared jail by carrying out civic duties as a penance – Carl would appear at demos, taking part famously in the 1971 May Day antiwar rally in Washington D.C.

Perhaps as an atavistic throwback, or a halcyon return to a more innocent time, Bruce Johnston’s ‘Disney Girls (1957)’ retreats into a bygone epoch; a hazy romanticist white westerner version of the 50s, complete with courting teens, who follow the protocols of love as laid down by the, “church, bingo chances and old time dances” set. Wistfully enchanting with its mandolin lead and faux-waltz timing, ‘Disney Girls‘ is saccharin sweet, yet also moving and touching – Brian called it “a masterpiece”. Johnston alludes to the comforting pull of a metaphorical rich naive escapist history: “Reality is not for me/and it makes me laugh/Fantasy world and Disney girls/I’m coming back”. Beautifully executed, sung and played, this almost quaint balled would prove to be one of the groups most endearing numbers – covered by Art Garfunkel and Cass Elliot.

Going even further back and recalling the Great Depression, Al Jardine’s ‘Lookin’ At Tomorrow (A Welfare Song)’, follows a roaming jobless destitute in his search for self-worth. Jardine hushes and murmurs a sad lament, full of sadly bewailed narrative: “I had to take to sweeping up some floors/I don’t mind that so much or the changing of my luck/but you know I could be doing so much more“, a sentiment echoed in our very own modern depression. Our protagonist still gleams for the fading light of hope, “I’ll be coming home tonight/Everything will be all right/And we’ll be looking at tomorrow”.

Completing ‘Surf’s Up‘ ragtag assortment of themes, Carl Wilson pens two sublimely elegiac, and soulfully profound minor opuses. The first, ‘Long Promised Road‘, slowly reveals itself over a stirring, tentative, delicately applied backing, before lifting towards a chorus that seeks to overcome the adversity in the emotionally loquacious lyrics. Carl uses a sweeping parable-esque flood of therapeutic soul-searching with such administered revelations as, “so hard to drink of passion nectar/When the taste of life is holding me down/So hard to plant the seed of reform/so set my sights on defeating the storm”. ‘Feel Flows‘ – apparently written in conjunction with Rieley – is pure moody “surf noir”, ripe with lapping percussion sleigh bells, rippling flute and meandering echo-effected phasered vocals: ‘Pet Sounds’ reaches maturity. An exercise in poetic philosophy, the recondite, layered text mystify and hints at self-discovery: “Unbending never ending tablets of time/record all the yearning/Unfearing all appearing message divine/eases the burning.” Carl shows that the Wilson gene ran throughout the family.

‘Surf’s Up‘ was released in August 1971 and made the Billboard top forty – the bands first LP since 1967s ‘Wild Honey’ to do so – easily surpassing their previous, and much admired ‘Sunflower’. But this minor success soon reversed itself as the group once again lost there way; relocating to Amsterdam on an expensive, near bankrupting whim – the awful result of this enterprise was the ‘Holland’ LP.

Chief in charge of operations, Rieley would be found out as a serial fibber – a private detective was hired to dig the dirt. Rather then the liberal advocate we’d been led to believe, Rieley would be outed as an employer of the ultra-conservative Stern Concern organization, recruited to infiltrate rock’n’roll groups who they believed might harbor subversive intentions. Remarkably, with that silver-tongued manner of his, Rieley talked his way out of both the fire and frying pan to continue working for the Beach Boys – however Bruce Johnston walked out.

For all of its faults – which I’ll agree there are many – and herculean efforts to drag this epic together, and link it in with a sympathetic theme, this album remains an intoxicating treat: perfectly encapsulating the times and the deterioration in one of pop/rocks greatest bands . No other Beach Boys album quite effects me in the same way; its appeal both personal and universal.

Beach Boys ‘Long Promised Road’