Released 1990.

Recorded at Greene Street, NYC; The Music Palace, West Hampstead NYC; Spectrum City, Strong Island NYC; June – Oct 1989.

SET YOUR CONTROLS TO THE HEART OF THE SUN

Here’s the paradox (so to speak): though ‘Fear Of A Black Planet’ is indeed one of Hip Hop’s greatest achievements; it’s also full of contradictory broadsides and diatribes that should more then worry your average white liberal – or any white person for that matter. The implications of Public Enemy’s lyrical tirades are to a point, unsettling: which is intentional. Salvos are blasted at homosexuals (‘Meet The G That Killed Me’), Hollywood (who frankly deserve it) and at the preconceived white conspired oppression.

There’s also the implications of the LPs loose and main theme: the pseudo-theories of the notable African-American psychiatrist, Frances Cress Welsing – her tracts, ‘Theory Of Colour Confrontation’, and to an extent, ‘The Isis Papers’, are used as the foundations. Cress’ corollary conclusions on race conclude that the white minority practice both a conscious and unconscious system of control, in an ongoing battle of survival, to ensure their (and mine) genetics continue. She seeks to arm those under the yoke with all the knowledge and intrigues of this system, so it can be dismantled. In addition to this, Cress controversially postulates on the melanin complex which claims that white people are genetic defects, descendants of mutated albinos who left Africa for their own good, and took on an highly aggressive nature to survive. Add to this the, appropriate, calls of indignation over disparaging comments made by Professor Griff on Jews (never the best move) – in particular the supposed statement that they were, “the majority cause of the wickedness” in the world – in an interview for the Washington Post in 1989. Much of the press, rightly so, called Griff to account – though he maintained these remarks were never made. Chuck D briefly fired him from the group, before bringing him back into the fold.

Their persona was already under suspicion; now it would receive a right royal backlash of accusations of racism and further thrust them towards disapproving scrutiny: the intensity of which added more kindling to the fires already roaring from the release of their 1988, agenda-defining, ‘It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back’. As a massive gesture of defiance, and bird-finger salute, ‘Fear Of A Black Planet’ would go on the attack. So the crux of the matter is: after all the rhetoric, why should a 15-year old white boy from the sticks find this record so appealing? A question that could be addressed to umpteen records, similar in black nationalistic tub-thumping. Maybe the connotations went over my head, or maybe it wasn’t the lyrics but the “wall of noise” production and multi-layered sampling and beats that attracted me. Looking back, it was a bit of both. My obsession with black history and Hip Hop, borne out of curiosity, and to a point, rebellion. And though it never directly spoke to me, it definitely made an impact and helped shape my thinking.

Conceived as a complex epic, which would mirror the highs and lows; builds and comedowns; the light and shade dynamics of a live performance, ‘FOABP’ would propel the group to global success; selling to a high percentage of white teens like myself. Intentionally a call to the black brethren to shape up and start taking action to better their plight; this universal heterogeneous album reached audiences far removed from the black community. Though its rousing, if not sometimes contentious, dispatch rattled many, its importance has been built-up to staggering levels of reverence. That whiter-then-white music bible, Rolling Stone (who ignored rap music for the best part of the 80s) placed this album at 300 in its all time 500 list, whilst even the upper echelons of the Library of Congress added to the National Recording Registry in 2005 – part, in some ways, of the establishment recognizing its importance.

ECLIPSE IN FULL EFFECT

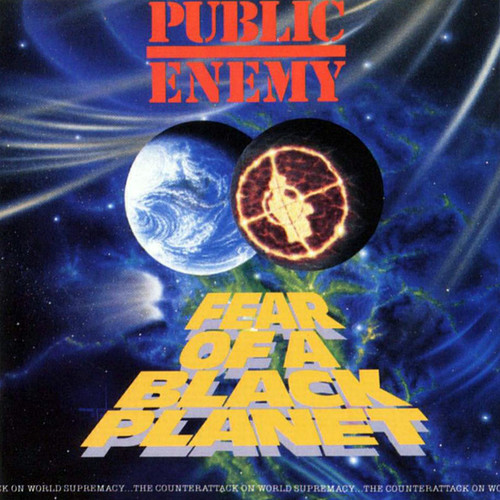

As reflected in many different musical genres, the importance of the 7in single had gradually waned as the album format began to take over. This, to some degree, kick-started the golden era of the late 80s; encouraging artists to experiment and concatenate their material, and take on concepts. It also spurred on the importance of artwork, which was usually an unimaginative affair; the group or artist, captured in various poses, set against the mean streets or up against a graffiti heavy wall. Public Enemy themselves once posed in a darkly lit bunker, now they had loftier aspirations, seeking out the unlikely NASA illustrator, B.E Johnson, to bedeck their epic with a monolithic-sized statement. Johnson didn’t disappoint, his P.E insignia scorched planet, eclipses the Earth, whilst below in faux-Star Wars/faux-Planet Of The Apes redolent stretched type-faced letters, the albums title appears to drift off towards the colliding, or passing, planets. Underneath the byline reads: ‘The Counterattack on world supremacy”, written out as a command in a quasi-ticker tape machine manner. Inside the impressive sleeve, the Bomb Squad production team went to work on creating a barricade of samples (figures vary between 150 to 160) and programmed beats. These were the days before copyright infringement was taken seriously; otherwise P.E would have parted with over half of the albums generated revenue just to pay usage rights. Recordings took place over a five month period, and involved a largely extended cast of studio bods, assistants and arrangers. The sheer scale of sequencing and programming – carried out on a Macintosh computer – coupled with a myriad of layering and textures, had the effect of creating, as the erudite music critic, Simon Reynolds, put it, a “claustrophobic” sound experience.

Aside from the prominent use of the drum machine (E-MU SP-1200) and sampler (AKAI S900), sessions were prompted by live jamming and improvisation – later tided up in post-production. The aforementioned Bomb Squad crew of Eric ‘Vietnam’ Sadler, Hank & Keith Shocklee, and Carl Ryder went supernova; thrust out into uncharted territories. It’s to their credit that this record avoided turning into a mess, and misfiring, as they skillfully managed to find enough space and separation in the mix to make sure everything fits. Guesting on the pyromaniac protest strong, ‘Burn Hollywood Burn’, Ice Cube would be impressed enough to entrust this production team with his inaugural debut, ‘AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted’ – he left N.W.A after a spat over royalties and direction. The raw rap heavyweight, Big Daddy Kane would also guest on this same track, adding an all too brief wise and assiduous diegesis on the plight of the black man’s role in the American movie industry.

Joker of the pack, Flavor Flav would fly solo on the opprobrious, sardonic wit pairing of ’911 Is A Joke’ and ‘Can’t Do Nuttin’ For You Man’. Additional voices, yelps (when not provided by James Brown a samples), sax and general clatter were dispensed by an expanding appendix of characters and players, who included the Wizard K-Jee (beefed up the scratching and dj duties alongside Terminator X), and a number of anonymous “performers”, such as Brothers James and Mike (see all credits above).

A DARKER SIDE TO THE MOON

Public Enemy’s magnum opus an rallying the troops styled trailblazer, begins with a prologue instrumental, and profound edict sampled introduction. ‘Contract On The World Love Jam’ is a ‘for whom the bells toll’, misty haunting vignette, crammed with wizened speeches: “The race that controls the past, controls the living present, controls the future”. In there you’ll find The Meters, Malcolm Mclaren, Billy Stewart and Bob James, all elbowing for room. These, usually beat-based and rap-free, interludes are scattered throughout; used as either breathers or as segue ways, connecting the main tracks. ‘Incident At 66.6 FM’ – geddit?! – features a torrid of abusive callers from a ‘hell is a white liberal radio hosts phone-in show’, directed at P.E. Alan Colmes is chief smug instigator, as our Chuck be-musingly chuckles at vilified comments like, “go back to Africa”.

‘Leave This Off Your Fu*kin Charts’ features a freak-beating , strident, jeep-beat, Main Source-esque backing with various itchy cutting and a bounty of Hall & Oates, Richard Pryor and old skool Hip Hop dignitaries (Grandmaster Flash and Big Daddy Kane) samples. Almost as a bookend to the opening titles the penultimate, ‘Final Count Of The Collision Between Us And The Damned’, is a more atmospheric, smokey apocalyptic tome; conjured up by the Bomb Squad, from the embers left after World War P.E.

The first immortalized rapped rhetoric lashing of the LP is unhurriedly turned loose on the kick-back-at-critics and call-to-action, ‘Brothers Gonna Work It Out’. Like an updated squalling re-think on ‘Science Fiction’ by Ornette Coleman, a wailing Prince borrowed lead guitar, flails about over a heaving squabbling mix of P.E’s own greatest hits and snatches of George Clinton’s ‘Atomic Dog’, and Sly’s ‘Sing A Simple Song’. Staying on the theme of comebacks or resurrections (though P.E weren’t really in need of one), ‘Welcome To The Terrordome’ is another insolent firebrand exercise in giving the media another black eye; answering their critics with a riotous aplomb. A maelstrom of rage, this siren heralded barrage of a tune explodes in a series of cyclonic whiplashes, and recycles the very best parts of the Soup Dragons’ ‘Mother Universe’, Kool & The Gangs’ ‘Jungle Boogie’, and The Temptations’ ‘Psychedelic Shack’, to name just a few. Chuck’s personal favorite, the Terrordome spits and recalls in a fury the deaths of Malcolm X and Huey Newton; Vietnam; the murder of Yusef Hawkins and the 1989 Virgina Beach riots; all coalesced together and delivered in an impassioned abrasive rave. That forceful Bomb Squad production continues on ‘Who Stole The Soul’; a fiery resentful bombast diatribe aimed at those who, “picked Wilson’s pocket”. Awash with its very own R&B shaking backing; collated from The Winstons (‘Amen Brother’), Sly – again – (‘Stand!’), James Brown (‘Make It Funky’ and ‘It’s A New Day So Let A Man Come In And Do The Popcorn’), and bizarrely, The Beatles (both ‘Getting Better’ and ‘A Day In The Life’); this wall of sound bites deep like a Black Panther run Stax and Watts riot in one.

My own personal choice, ‘War At 33 1/3′, is a similar blistering assault on the senses, as Chuck raps at the fastest setting yet; almost tripping up over his own rapid syllable hurdling lyrics; bouncing along to the backroom teams seering, throbbing attack drums and seething howls.

The anthemic 1989 hit, ‘Fight The Power’ is left till the very end, its rebel rousing vociferating agenda set to leave an indelible mark. Used as both the soundtrack for that summer, and replayed throughout Spike Lee’s ‘Do The Right Thing’ movie, ‘Fight The Power’ features Chuck’s sparring rebuffs and bounding over an hardcore nu-jack swing – ‘Teddy’s Jam’ by Guy – and frazzled funk-kicking, sample-rich backing (there’s at least 14 tracks used, from Uriah Heep to Bobby Byrd). Remembered not just for its distinctive jeep-beat, guitar chopping, “funky drummer”, and scratched organ roll, but it also features those immortal lines: “Elvis was a hero to most, but he never meant shit to me you see, straight up racist that sucker was simple and plain, Mother fuck him and John Wayne”.

That instilled “fear of a black planet” mission statement (summed up on the LPs sleeve – “Black power 1990 is a collective means of self defense against the worldwide conspiracy to destroy the Black Race. It’s a movement that only puts fear in those that have a vested interest in the conspiracy, or that think that it’s something other than what it actually is…”, is explored on both the title track, and to some extent on ‘Pollywannacracka’. ‘FOABP’ is a slinky, R&B affair, which has a Hammond organ pumping out a sleazy club lounge, Stax revue like riff, whilst Chuck questions racial purity and the”look whose come to dinner” stereotyping of white/black dating – also the main thread running through the Issac Hayes smoothly ministered, ‘Pollywannacraka’. A strange fatuous, smurf-esque voice reminds us, “… white comes from black”, in a slightly niggling way, to reinforce the ilogical prejudices of us Europeans.

Self-styled “joker” of the group, Flavor Flav, ‘bojangles’ his way across his cuts. Apart from the premonitory dial-code, ’911 Is A Joke’ has Flav unfurl his curt-tongued witty observations on the emergency services slow response to help out a brother or sister in need, especially if they call from certain unsavory corners of the city. He delivers a efficacious denunciation: “Now I dialed 911 a long time ago, don’t you see how late they’re reactin’. They only come and they come wanna they wanna, so get the morgue truck embalm the goner”. His second solo joint, ‘Can’t Do Nuttin’ For You Man’ unravels some sorry tale of deceit and scamming: ‘Make ya love the wrong instead of right, not a thief cat burglar through the night, cop told your girl her name was Shirl, about a rooftop crime to steal her pearls”. These soul-rattling jamborees prove to be among Flav’s finest contributions to the P.E catalog.

A Hip Hop LP wouldn’t be right without the customary guest slots. ‘Burn Hollywood Burn’ features two of raps most happening artists of the time. Originator supreme and rough’n’ready maverick, Big Daddy Kane, alongside the West Coast miscreant, Ice Cube, both add spite and spit to this incendiary bemoaned put-down of the movie business. Questioning the lack of leading black actors/actress parts and films, they spoil for a fight against “Sunset Boulevard”, dismissing enforced stereotypes and sighing with disbelief at ‘Driving Miss Daisy’. The Big Daddy gets the best of it, showing off a pretty assiduous and poetically tempered flow: “As I walk the streets of Hollywood Boulevard, Thinkin’ how hard it was to those that starred, in the movies portrayin’ the roles of butlers and maids slaves and hoes. Many intelligent Black men seemed to look uncivilized when on the screen, like a guess I figure you to play some jigaboo, on the plantation, what else can a nigger do?”. Cube name checks his buddies before delivering a brief re posit: “Roamin’ thru Hollywood late at night, red and blue lights what a common sight, pulled to the curb gettin’ played like a sucker, Don’t fight the power … the mother fucker!”. Both are way too brief, yet they stamp authority.

‘Fear Of A Black Planet’ stands as a totem to ambition in the Hip Hop genre. 21-years on, and it still sounds like a cannonade of protest. In this modern retro-obsessed appropriation era, we don’t always revisit the best parts of the past, like 1989/1990; an epoch that produced a whole impressive catalog of records. Whether you agree or not with the rhetoric, our times could do with a modern P.E, or at least a ballsy, uncompromising album, like their 1990 classic.